Just nine months ago, the forests and farmlands of the continental United States were well-watered, with just 5 percent of the nation facing drought. By February 2018, after dry autumn and winter weather across many states, drought has reached its highest levels since the spring of 2014.

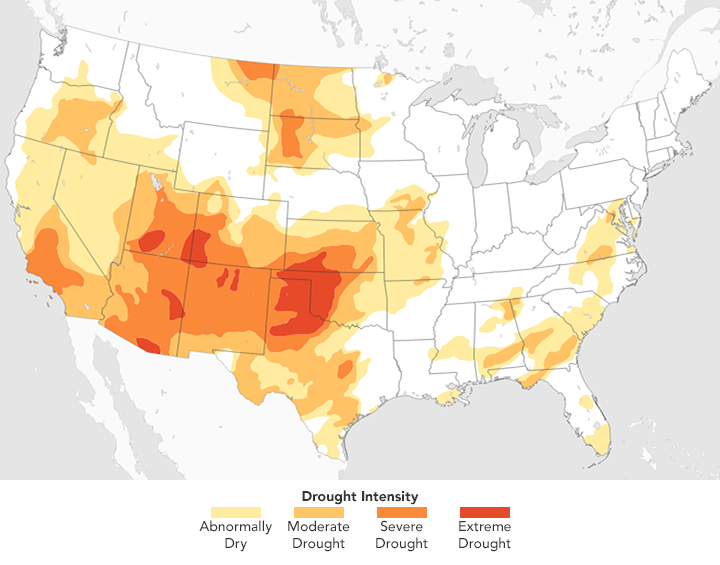

The map at the top of this page was compiled from data provided by the U.S. National Drought Monitor, a partnership of U.S. Department of Agriculture, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. It depicts areas of drought on February 27, 2018, in progressive shades of orange to red. It is based on measurements of climate, soil, and water conditions from more than 350 federal, state, and local observers.

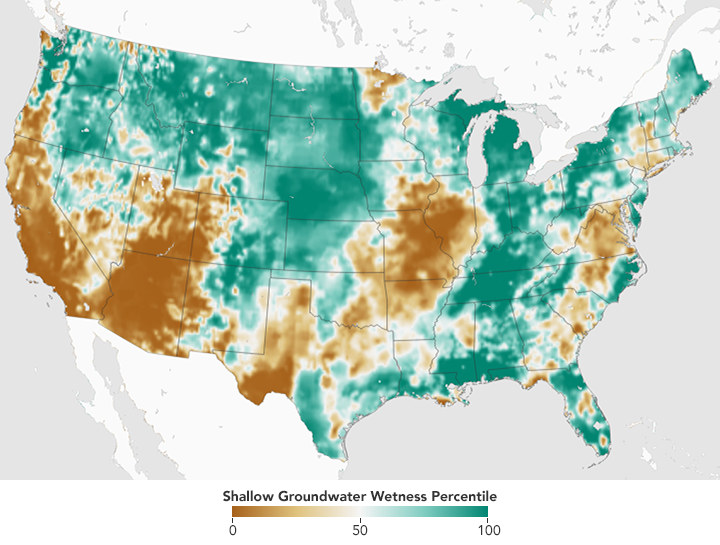

The second map shows the water woes a bit deeper underground. Developed by scientists at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, this data set combines observations from satellites and ground-based gauges to model the relative amount of water stored in underground aquifers in the continental United States. The wetness, or water content, is a depiction of the amount of groundwater on February 26, 2018, as compared to the average from 1948 to the present. Areas shown in teal have more abundant groundwater for this time of year than the long-term average, while shades of brown depict deficits. The maps are an experimental product used by the U.S. Drought Monitor.

As of February 27, 2018, an estimated 55 percent of the continental U.S. was classified as abnormally dry, and 31 percent of the country was affected by some level of drought—17 percent in severe to extreme drought. The worst drought in recent history, 2012, saw nearly two-thirds of the U.S. affected by drought.

Nearly all of Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona, and Colorado are now afflicted by drought conditions. The entire state of Oklahoma is parched, and nearly 33 percent of that state is facing extreme drought. North and west Texas, as well as the entire state of Missouri, is also coping with serious rainfall deficits. After emerging last year from a five-year drought, California is creeping back toward seriously dry conditions. Snowpack also has been low this winter across much of the Rocky Mountain range, meaning there will be less meltwater flowing down into southwestern rivers this summer.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using data from the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Story by Mike Carlowicz.