As global temperatures continue to rise, the prevailing wisdom in the climate science community is that droughts will grow more frequent and more extreme in the 21st century. Though temperatures were already rising in the 20th century, the global trend in drought length and severity was ambiguous, with no clear pattern. However, the impacts of droughts was less ambiguous, particularly in recent decades.

In a study published in August 2017 in the journal Nature, researchers from 17 institutions found that more of Earth’s land surface is now being affected by drought and ecosystems are taking longer to recover from dry spells. Recovery is particularly worse in the tropics and at high latitudes, two areas that are already pretty vulnerable to global change.

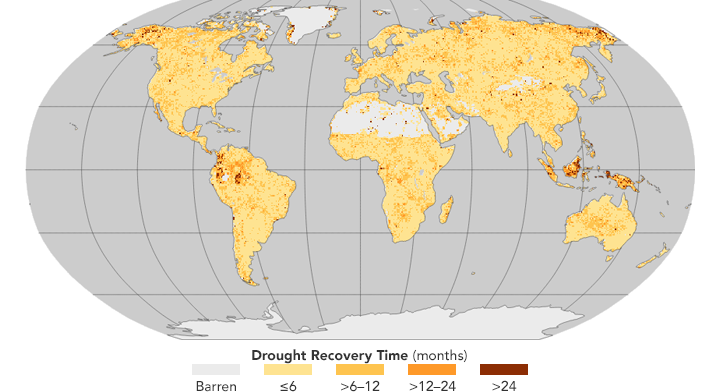

The map above is based on data from that study, which was led by Christopher Schwalm of Woods Hole Research Center. It depicts the average length of time that it took for vegetation to recover from droughts that occurred between 2000 and 2010. The darkest colors mark the areas with the longest drought recovery time. Land areas colored light gray were covered by ice or sand (deserts).

Up until now, most assessments of drought and recovery have focused on the hydrology; that is, has new rain and snowfall made up for the deficit of water in rivers, lakes, and soils? In this new study, researchers focused on the health and resilience of the trees and other plants because full reservoirs and streams do not necessarily mean that vegetation has recovered.

The research team combined observations from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA's Terra satellite, ground measurements, and computer models to assess changes in drought. In particular, they measured changes in gross primary productivity, or how well plants are consuming and storing carbon dioxide through photosynthesis. As the analysis showed, plants in many regions are taking longer to recover from drought, often because weather is more extreme (usually hotter) than in the past.

If the time between droughts grows shorter (as predicted) and the time to recover from them keeps growing longer, some ecosystems could reach a tipping point and change permanently. This could affect how much carbon dioxide is stored on land in trees and other vegetation (the land “carbon sink”). If less carbon is being captured and stored, then more of what humans produce would remain in the atmosphere, creating a feedback loop that amplifies the warming that leads to more drought.

“The most important implication of our study,” said Schwalm, “is that under business-as-usual emissions of greenhouse gases, the time between drought events will likely become shorter than the time needed for recovery.”

“Using the vantage point of space, we can see all of Earth’s forests and other ecosystems getting hit repeatedly and increasingly by droughts,” added co-author Josh Fisher of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “Some of these ecosystems recover, but, with increasing frequency, others do not.”