On February 4, 2017, the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 acquired natural-color images that beautifully demonstrate the variety of ice types that can form in the northern Caspian Sea.

The Caspian stretches about 1,000 kilometers (600 miles) from Kazakhstan to Iran. In the north, temperatures are colder, and the water is fresher (less saline) and shallower. As a result, northern areas are more prone to freezing in wintertime.

The first image shows the northwestern Caspian where it meets western Kazakhstan. The brown areas are part of the Volga Delta. Just offshore, in the shallowest parts (only meters deep), a well-developed expanse of consolidated ice appears white. Farther offshore, a large field of old, hummocked, white and gray-white ice has detached. (When pieces of ice are pushed together, some ice is forced upward and downward into so-called ‘hummocks.’) This ice is slowly drifting in a giant polynya which is covered by young, thin ice (nilas).

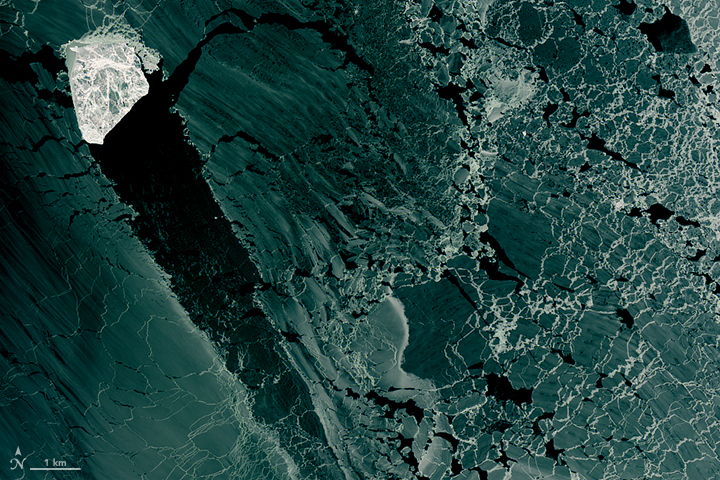

The second image shows a detailed view of the nilas ice, which appears dark. Perhaps most notable, however, is the white, diamond-shaped piece of ice parked right in the middle. “This ‘island’ of white ice is most probably a piece that detached from the ice field,” said Alexei Kouraev, a scientist at the Laboratory of Geophysical and Oceanographic Studies (France). He notes that a likely point of origin is the “dent” of similar size in the boundary of the white ice (mid-right of the top image).

It might look like that ice diamond is on the move, cutting a path through the thinner cover. But it’s more likely that the chunk of ice broke away from the thicker sea ice and became grounded—anchored to the bottom of the sea. The grounded ice (‘stamukha’ in Russian) is not moving, according to Kouraev. Instead, the wind is pushing the thin ice around this grounded ice, creating a ‘shadow’ of open water behind it.

Grounded ice is particularly apparent in the third image. This false-color image shows thermal data: orange depicts where the surface is warmer, which tends to be where the ice is thinnest; blues and whites are colder areas, including the main ice pack and grounded ice.

With the advance of spring and rising temperatures, ice on the Caspian will soon disappear. All of the ice is first-year ice, meaning that it should not survive the summer. But with the melting of the ice, a different picture can emerge: the keels of hummocked ice that once reached all the way to the seafloor can leave behind scour marks.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Caption by Kathryn Hansen, with image interpretation by Alexei Kouraev and Piter Bukharitsin.