What was once a good thing for Adélie penguins is becoming too much of a good thing.

For thousands of years, spells of warm weather along the coast of Antarctica helped penguin populations thrive. Milder weather meant more bare-rock locations for the birds to lay their eggs and nurture their chicks, as well as less stress on the parents and newborns and less sea ice to fight through in the harbors.

But over the past few decades, some parts of the southern continent have turned too warm—particularly the water—due to global climate change. According to a new study, that warmth is likely to change where Adélies can raise chicks.

Using observations of penguin populations and of environmental conditions, as well as computer models of projected environmental changes, the team of researchers projected that nearly a third of Adélie penguin colonies around Antarctica (representing about 20 percent of the total population) could be in decline by 2060. By the end of the 21st century, as much as 60 percent of the colonies could be in trouble. On the other hand, some new refuges on other parts of the coast could open up and offset the losses.

The study was led by Megan Cimino, a biological oceanographer who recently earned her doctorate from the University of Delaware; she is now a postdoctoral scholar at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Scientists from Stony Brook University, the University of Delaware, and the National Marine Fisheries Service also contributed to the paper, which was published in Scientific Reports on June 29, 2016.

“It is only in recent decades that we know Adélie penguins population declines are associated with warming, which suggests that many regions of Antarctica have warmed too much and that further warming is no longer positive for the species,” said Cimino.

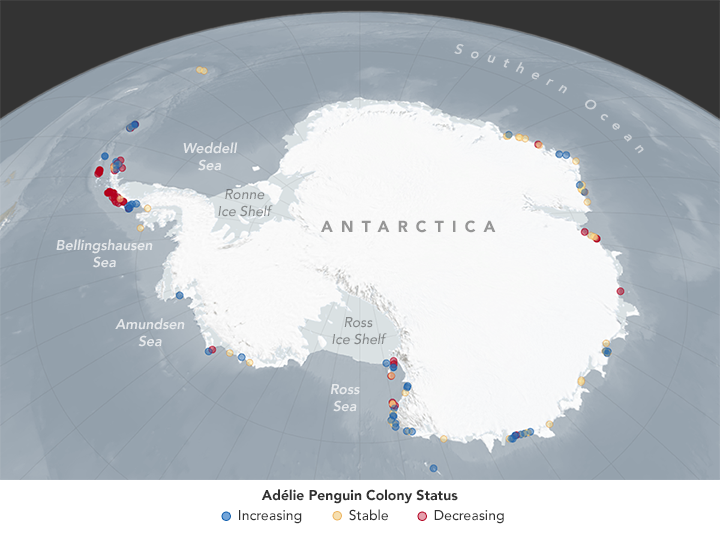

The map at the top of this page shows the population trends for Adélie penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae) colonies in Antarctica over the past few decades. (Some colonies were not mapped because the current status and trend are not known.) The map was built from from previous observations (in-person counts and satellite studies) of penguin populations. Red dots mark colonies that have been declining in population—most notably along the Antarctic Peninsula, one of the fastest-warming places on Earth. Blue dots show the location of growing colonies, which often matches where temperatures have been stable or somewhat cooler. Yellow dots denote stable penguin populations.

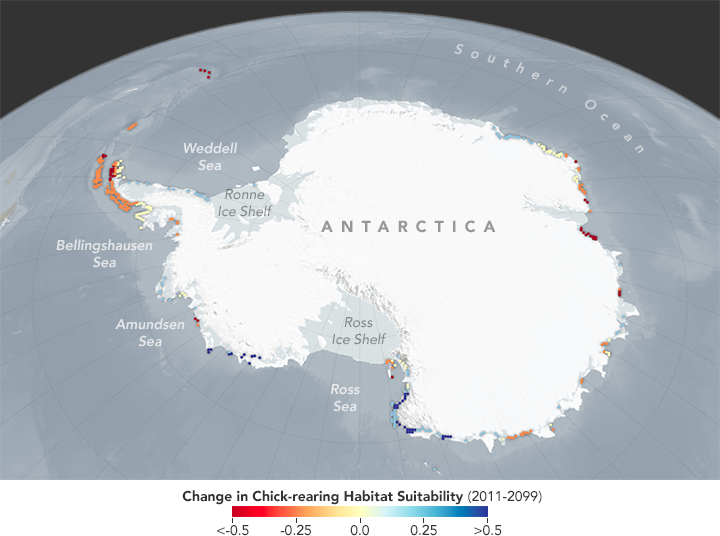

The second map shows the output of “habitat suitability models” in which the science team plugged in data on past conditions around penguin colonies while projecting various scenarios in future water temperatures and sea ice concentration. Shades of red indicate areas where habitat is likely to be less suitable for raising penguin chicks as the world warms; blue areas are likely to become more favorable. The photograph below shows Megan Cimino and some Adélie penguins near Palmer Station on the West Antarctic Peninsula in February 2015.

Warmer temperatures can open up land-based habitat for the penguins, while also keeping waterways ice-free and making it less arduous to search for food. But those warmer temperatures can also make the waters less hospitable (too warm; too little plankton) for the krill and fish that penguins eat. On the other hand, some coastlines could become more hospitable in the future—warming enough to create more habitat, but not enough to disrupt the food supply. The Cape Adare region on Ross Sea is one such area.

NASA Earth Observatory maps by Joshua Stevens, using data courtesy of Megan Cimino/University of Delaware. Photo courtesy of Megan Cimino/University of Delaware. Caption by Michael Carlowicz.