In the winter, the coast of Peru is a very cloudy place. In this part of the Pacific Ocean, the Humboldt Current provokes coastal upwelling; that is, cooler water from the ocean depths are pulled up to the surface. The cooler water chills the air above, causing water vapor to condense into water droplets and, eventually, low clouds. These lumpy, sheet-like clouds are called marine stratocumulus, the most common cloud type in the world by area.

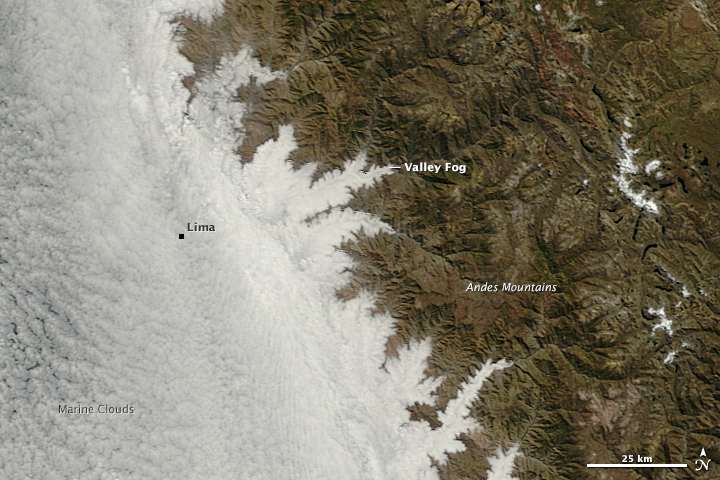

When the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite passed over coastal Peru on June 7, 2015, sheets of marine stratocumulus clouds were meeting the dry coastline of Peru, outlining the coastal geography in dramatic fashion. Patches of both open- and close-celled low clouds are visible offshore. Open-cell clouds look like empty compartments, whereas close-cell clouds look like compartments stuffed with cloud. Despite their moisture-free appearance, pockets of open cells are actually associated with the development of precipitation. Uninterrupted decks of closed-cell stratocumulus clouds produce little to no drizzle, while pockets of open cells form as drizzle begins to fall.

Along the coast, the cloud layer has pushed in to cover Peru’s coastal plain, obscuring Lima and the other cities along the coast. Since the marine clouds are low—just a few hundred meters off the ground—the Andes Mountains block their eastern movement. The river valleys are the only places moist and cool enough for the low clouds, or fog, to persist. In the lower, close-up image, notice how tendrils of fog trace the river valleys.

Low clouds are so common over coastal Peru that locals have a name for the phenomenon: garúa, which means “drizzle.”

NASA image by Jeff Schmaltz, LANCE/EOSDIS Rapid Response. Caption by Adam Voiland.