Although accidents and hurricane damage to infrastructure are often to blame for oil spills and the resulting pollution in coastal Gulf of Mexico waters, natural seepage from the ocean floor introduces a significant amount of oil to ocean environments as well. Oil spills are notoriously difficult to identify in natural-color (photo-like) satellite images, especially in the open ocean. Because the ocean surface is already so dark blue in these images, the additional darkening or slight color change that results from a spill is usually imperceptible.

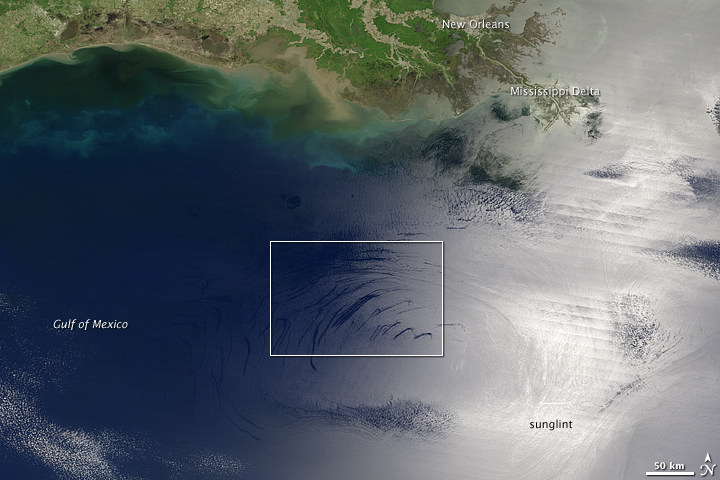

Remote-sensing scientists recently demonstrated that these “invisible” oil slicks do show up in photo-like images if you look in the right place: the sunglint region. This pair of images includes a wide-area view of the Gulf of Mexico from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite on May 13, 2006 (top), and a close up (bottom) of dozens of natural crude oil seeps over deep water in the central Gulf.

The washed-out swath running through the scene is where the Sun is glinting off the ocean’s surface. If the ocean were as smooth as a mirror, a sequence of nearly perfect reflections of the Sun, each with a width between 6-9 kilometers, would appear in that line, along the track of the satellite’s orbit. Because the ocean is never perfectly smooth or calm, however, the Sun’s reflection gets blurred as the light is scattered in all directions by waves. The slicks become visible not because they change the color of the ocean, but because they dampen the surface waves. The smoothing of the waves can make the oil-covered parts of the sunglint area more or less reflective than surrounding waters, depending on the direction from which you view them.

The usual technique for mapping oil slicks from space uses radar, which bounces pulses of radio waves off the wave-roughened surface of the water and detects the amount of backscattered energy. The downside of using space-based radars to map oil slicks is that they don’t provide routine coverage of large areas, and oil slicks may evaporate or disperse significantly within a day. The researchers suggest that tracking oil slicks in the wide sunglint region of daily Terra and Aqua MODIS images may be a better avenue for comprehensive, near-real-time monitoring of large oil spills and natural seeps in marine ecosystems.