In the Grand Sud region of southern Madagascar, the “lean season” typically arrives in September or October. It is the time of year when rains are minimal, fields and grasslands dry out, and zebu cattle herds survive on whatever scraps they can find in parched spiny forests and savanna grasslands. Sometimes called the kere, or hunger, this is the time of year when cattle thefts and conflict increase and food shortages intensify.

The kere comes to the poorest parts of southern Madagascar every year, but food aid groups are warning that the 2022 kere is poised to be particularly perilous. Humanitarian groups have warned that food insecurity is approaching an “emergency” phase on the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification scale, the second-most serious category. Among the hardest hit areas are the Betioky and Ampanihy districts in the Atsimo-Andrefana region.

The map at the top of the page illustrates the scope of the challenge in southern Madagascar. It depicts anomalies in the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), a measure of how plants absorb visible light and reflect infrared light. Drought-stressed vegetation reflects more visible light and less infrared than healthy green vegetation, and this can be detected by satellites. This NDVI anomaly map, based on data from the Landsat program, compares the health of vegetation between September 2021 and September 2022 versus the average for the same period from 2000-2015. Brown areas show where plant health or “greenness” was below normal. Greens indicate vegetation that is more widespread and abundant than normal.

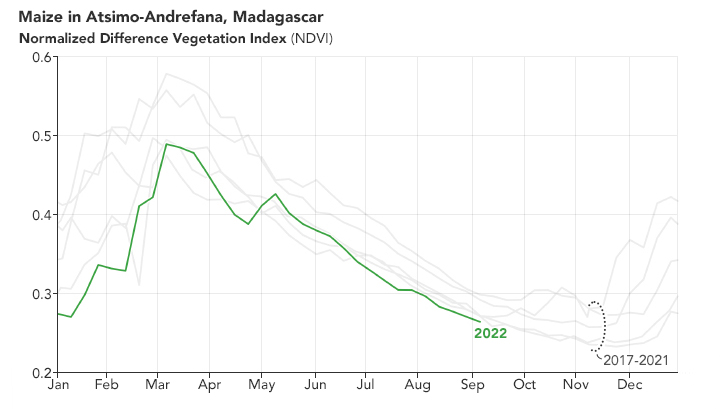

The NASA Harvest program, with international partners from the GEO Global Agricultural Monitoring (GEOGLAM) initiative, has developed several tools, including the Agmet Earth Observation Indicators, to monitor environmental factors relevant to food security. The chart above shows data from that tool. Based on NDVI observations, the health of the 2022 maize crop in Atsimo-Andrefana was the worst the area has seen in the past five years. Crop health during the previous two years was nearly as bad. Maize is normally harvested in mid-April.

Three consecutive years of drought put a severe strain on subsistence farmers. Swarms of armyworms and locusts damaged crops. Yields plummeted as rainfall dropped to half of normal in some parts of the Grand Sud. The maize crop in southern Madagascar was particularly hard hit, with the 2022 harvest down by 70 percent. In certain areas, too much rain also exacerbated problems. In 2021 and 2022, several tropical cyclones brought winds and rains that damaged many crops and put more strain on farmers.

Planting for next year’s maize and legume crops typically starts in October in southern Madagascar, but the timing depends on the start of the rains. “La Niña is currently present, which usually brings above-average rains to much of Southern Africa, and forecasts are indicating the rains will start on time,” explained NASA Harvest researcher Christina Jade Justice. “However, there are still significant soil moisture deficits from the consecutive below-average seasons that will still need to be overcome. The high prices of fertilizer, seed, and gas could also cause problems for farmers.”

NASA Earth Observatory image by Lauren Dauphin using data courtesy of Ritvik Sahajpal/University of Maryland/NASA Harvest, and Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Adam Voiland.