For elephants roaming the savanna in Kenya, drought can be a matter of life and death. Prolonged periods with little to no rainfall can cause vegetation to wither, leading the colossal animals to starve to death.

About one-third of Kenya’s elephants can be found in the Tsavo Conservation Area in the southern part of the country. As of 2011, the area supported 12,000 elephants. That population was once a lot larger; in 1974, you would have found about 35,000 elephants. Previous research attributed much of the decline to drought. But Yussuf Wato, a wildlife ecologist at Wageningen University (Netherlands), wanted to know more.

To investigate the relationship between drought and elephant mortality, Wato and colleagues collected information on deaths, rainfall, locations of water sources, elephant population density, and a space-based measure of vegetation health or “greenness.” These data, collected between 2004 and 2012, became part of a model to determine the probability of death during the wet and dry seasons.

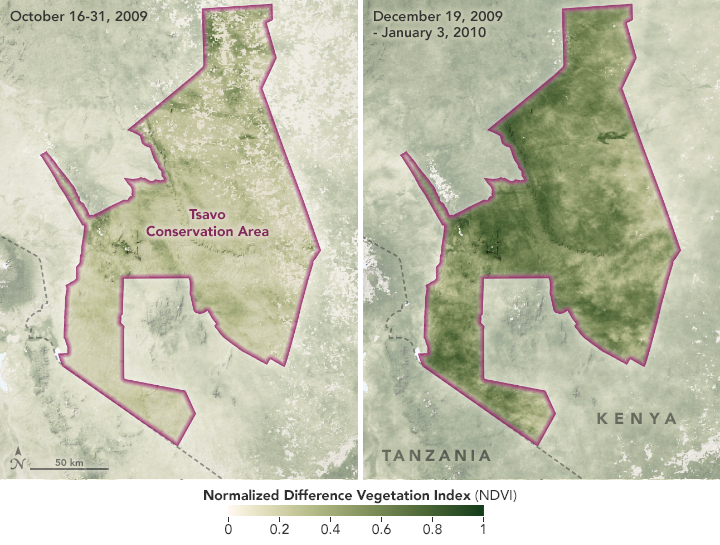

The satellite-derived “greenness” is important because it allows researchers to track the health of vegetation in a region. The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) measures how plants absorb and reflect light; the more infrared light reflected, the healthier the vegetation. In their study, scientists used landscape greenness to represent the availability of food during the wet and dry seasons over a span of nine years.

The maps above show NDVI during two distinct seasons. NDVI data acquired between October 16-31, 2009, (top-left map) show very low values, or not much greenness, indicating that vegetation was suffering. October marks the end of a long dry season that begins each June. It is typically preceded by a long wet season that runs from mid-March to May. In 2009, however, the wet season brought little rainfall, setting the stage for an even harsher dry season. In October 2009, more elephants died than in any other part of the study period.

“This finding suggests that the long wet season determines the number of months that the forage will remain available in the long dry season before elephants succumb to starvation,” the authors wrote in their paper.

Vegetation can quickly return, however, as demonstrated by high NDVI values just a few months later (top-right map). November and December are typically marked by a short wet season, which renews food sources to the elephants fortunate enough to survive the dry season.

“Our results suggest that elephant populations in arid and semi-arid savannas appear to be regulated by drought-induced mortalities,” the authors wrote, “which may be the best way of controlling elephant numbers without having to cull.”

NASA Earth Observatory maps by Joshua Stevens, using MODIS NDVI data from the Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (LPDAAC) and Google Earth Engine. Story by Kathryn Hansen.