The November 2018 Woolsey Fire in Southern California left more than a vast burn scar on the landscape. For months it also left unusually high levels of fecal bacteria and suspended sediment in the coastal waters off Los Angeles and Ventura counties.

For a new study published in Nature Scientific Reports, scientists combined satellite imagery, precipitation data, and water quality reports to assess two standard parameters for coastal water quality after the fire: the presence of fecal indicator bacteria and the turbidity, or cloudiness, of the water. When it rains, runoff typically carries some bacteria and sediment from the land into coastal waters. But the huge spike in both following the fire was anything but typical.

Fecal indicator bacteria originate in the gastrointestinal tracts of humans and other warm-blooded animals. While fecal indicator bacteria are not harmful, they can indicate the presence of other potentially harmful bacteria and pathogens found in feces. Turbidity has other implications: Cloudy, murky water results in less sunlight reaching marine life like kelp and phytoplankton.

“Post-fire, we saw drastic water quality changes, particularly at beaches draining the burned area,” said the study’s lead author, Marisol Cira, a doctoral candidate at the University of California, Los Angeles, and an intern at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). “In those areas, both total coliform bacteria and enterococcus were far greater than pre-fire levels, as was turbidity plume size.”

The researchers concluded that the post-fire monthly average of total coliforms—a large group of fecal indicator bacteria that can be found in soil, on plants, and in human waste—was ten times higher than it was for any month in the previous twelve years. Enterococcus, which indicates the presence of bacteria that can cause gastrointestinal disease, was 53 times higher, well above what is considered safe for recreational use of the water. (Local authorities issued water quality warnings at the time.)

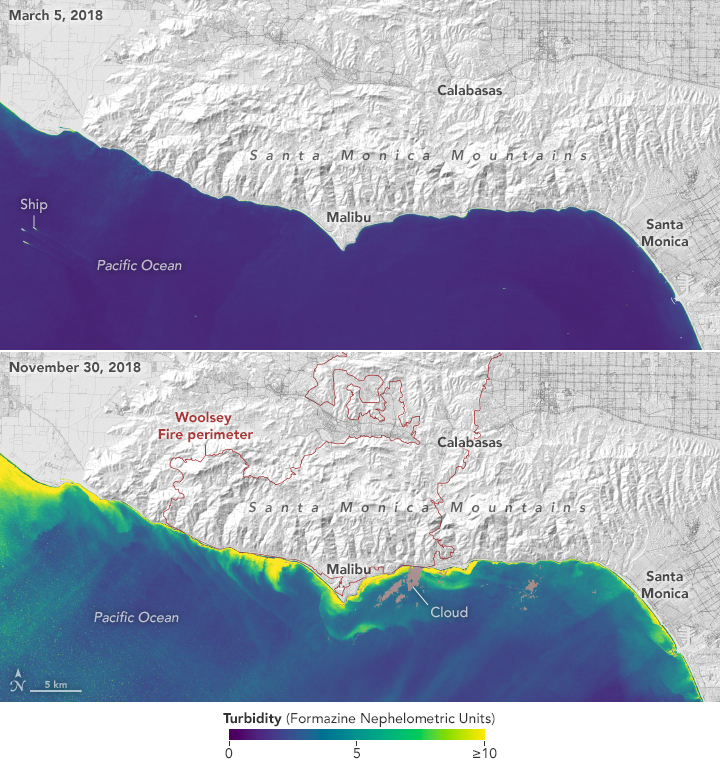

The maps above show satellite measurements of turbidity off the Southern California coast in March 2018, before the Woolsey Fire, and in late November, after it had consumed nearly 100,000 acres of forest and chapparal. The natural-color image below shows turbid coastal waters on November 30, 2018, as observed by the European Space Agency’s Sentinel 2 satellite.

Cira and colleagues found that bacteria levels remained high through February 2019 and took six months to return to pre-fire levels. Turbidity remained high for three months before returning to previous levels.

To assess turbidity levels, the study team analyzed satellite imagery from before, during, and after the fire. They were able to estimate the size of sediment plumes that moved into coastal waters following rain events, when turbidity levels usually increase. They found that the surface areas of turbidity plumes during the first storm following the Woolsey Fire were about 10 times greater than those following similar rain events from pre-fire years.

During normal conditions, soil absorbs much of the water that falls when it rains, preventing a lot of bacteria and sediment from making its way to the coast. But after a fire, that is not the case.

“When a fire burns through a forest, it increases the amount of vegetation litter on the ground and changes the chemistry of the soils in a way that makes them unable to absorb water,” said Christine Lee, a study co-author at JPL. “So rather than getting absorbed into the soil, rain runs off into local water bodies and coastal systems, carrying sediment and bacteria with it.”

The researchers also examined the amount of post-fire fecal indicator bacteria in the water under different weather conditions. They found that more bacteria were present in wet weather than in dry weather; but in both cases, average monthly bacteria levels showed dramatic and prolonged increases over pre-fire levels.

“Usually when there’s a spike of bacteria in the water, it only lasts a day or two,” said Luke Ginger, scientist and study coauthor from the nonprofit group Heal the Bay. “But after the fire, there were months of sustained high bacteria. So that was a big concern.”

Wildfire seasons are becoming longer and more intense due to climate change; in fact, the seven largest California wildfires on record have occurred during the past four years. “Climate change will likely exacerbate the effects we see here in terms of water quality as wildfire and rainfall patterns continue to change,” said Ginger. “A key part in protecting our ecosystems and communities is understanding these emerging threats and spreading awareness about them.”

While this study examined only the effects of the 2018 Woolsey Fire, an upcoming NASA project called KelpFire (funded by NASA’s Minority University Research and Education Program) will explore additional coastal watersheds in California. This effort will dive deeper into how fire-related impacts like those discussed in this study affect the greater coastal ecosystem, such as kelp forests.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using data from Cira, Marisol, et al. (2022) and using modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2022) processed by the European Space Agency. Story by Esprit Smith, NASA’s Earth Science News Team.