The 2018 fire season in California has been record-breaking. The Mendocino Complex in July was California’s largest fire by burned area on record, destroying nearly half a million acres. The Camp Fire in November was the deadliest and most destructive in state history, completely wiping out the town of Paradise.

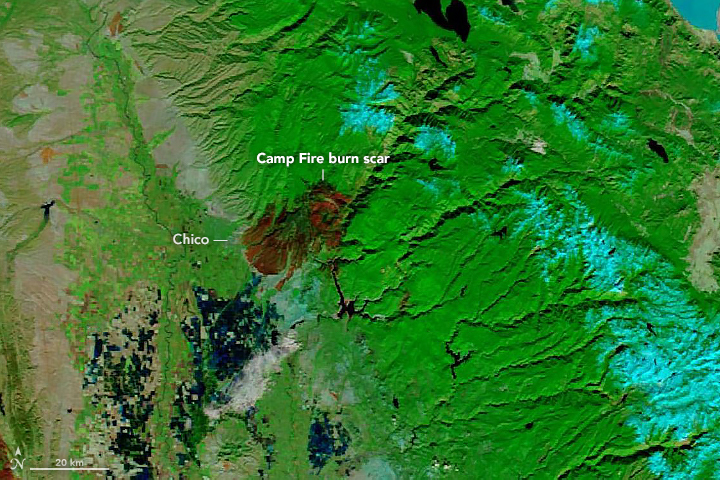

The image above shows the charred land—known as a burn scar—from the Camp Fire, which has destroyed more than 18,000 structures and caused at least 85 deaths. The fire, which has burned more than 153,000 acres, is now fully contained, according to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. This image was acquired by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite on November 25, 2018.

The second image shows a wide view of Northern California, where burn scars from nine major 2018 fires are visible from space. The image was acquired by Terra MODIS on November 25, 2018.

“Every year, we keep hearing fires labeled as ‘the biggest’, ‘worst’, and ‘deadliest’,” said Amber Soja, a wildfire scientist at NASA’s Langley Research Center. “We keep hearing that this is the ‘new normal.’ Hopefully it’s not true for long, but right now it is.”

California’s fire activity in 2018 is part of a longer trend of larger and more frequent fires in the western United States. Of the total area burned in the West since 1950, 61 percent of it has occurred in the past two decades, according to Keith Weber, GIS Director at Idaho State University and principal investigator of the NASA project RECOVER. “The 2018 fire year is going to fit right in to what's been going on the last decade or two. In fact, it might be a taller spike in the overall trend.”

High temperatures, low relative humidity, high wind speed, and scarce precipitation have increased dryness and made live and dead vegetation in western forests easier to burn. “Those fire conditions all fall under weather and climate,” said Soja. “The weather will change as Earth warms, and we’re seeing that happen.”

Soja also noted that California had a really wet winter in 2017, which helped build up grass and brush in rural and forested areas. The vegetation was an abundant fuel source as California headed into the 2018 dry season, which was exceptionally dry and lasted into late October.

As fires are becoming more numerous and frequent, NASA’s Disasters Program has been working with disaster managers to respond to the blazes. For California’s Camp Fire and Woolsey Fire, NASA scientists and satellite analysts have been producing maps and damage assessments of the burned areas, including identifying areas that will be more susceptible to landslides in the upcoming winter.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS/LANCE and GIBS/Worldview. Story by Kasha Patel.