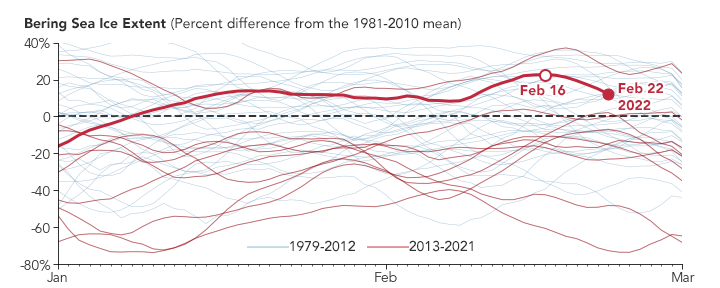

In 2022, the floating ice cover in the Bering Sea reached its greatest extent for early to mid-February since 2013. By February 13, the sea ice had reached St. Paul in the Pribilof Islands for the first time since March 2020. The ice growth is an outlier amid a long-term decline.

In the Arctic, where annual average temperatures have increased more than three times as fast as the global average, the sea ice extent is declining. This is true especially in summer, but also year-round, in nearly every region—except the Bering Sea, said Walt Meier, a sea ice researcher at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC). "The one exception has been the Bering Sea during late winter and early spring (February to April), where there is an increasing trend," said Meier. The reasons for this are not totally understood, but may relate to multidecadal variability in the northern Pacific Ocean, he added.

The map above shows the extent sea ice in the Bering Sea on February 16, 2022, when it covered more than 846,000 square kilometers (327,000 square miles), exceeding the 1981–2010 mean. (Ice extent is the area with at least 15 percent ice cover, the minimum at which space-based measurements give a reliable measurement.)

"Even with the winter increasing trend, there is a lot of variability," Meier said. For example, the winter of 2018 saw a record low for the Bering Sea, with almost no ice for much of the winter. In fact, the winter of 2018 brought less ice to the Bering Sea than any winter since the start of written records in 1850. Sea ice was scarce in the following year as well, with February 2019 extents ranking just above 2018.

The chart above compares the sea ice extent in the Bering Sea each year to the 1981–2010 mean as the percent difference from that mean. In the past decade, only two years—2013 and 2022—rose above the mean. The winter growth trend can be seen in years that fall below the mean as well.

On time scales of weeks to months, wind and weather play a large role in the formation and extent of Bering Sea ice. In the first two weeks of February 2022, an area of low atmospheric pressure developed over the North Pacific Ocean. This drew cold winds from the north and from the east off Alaska, which chilled surface waters and facilitated freezing. The north winds then blew that ice south, expanding the ice pack.

Unlike most other Arctic seas, the Bering is open to the ocean (except where it is hemmed in by the Aleutian Islands), allowing the ice to expand unimpeded. "The [Bering Sea] ice is also quite thin and mobile, so it can move quickly with winds, and grow or melt based on the temperature," Meier said. But when the sea-level pressure pattern changes, the winds shift, and the ice edge can quickly retreat north. By February 20, winds blowing out of the south had moved the ice north and away from St. Paul Island.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using data from the National Snow and Ice Data Center. Story by Sara E. Pratt.