The 2019-2020 winter was warm for most of the middle latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere. Not so in the Arctic, where persistent cold air helped sea ice grow to a larger extent than in several recent years. Still, there was not enough growth during the fall and winter months to bring sea ice back to long-term average levels.

“So far this year the Arctic sea ice has been more extensive than in most years of the past decade, but it is not close to as extensive as it typically was in the 1980s and 1990s,” said Claire Parkinson, a sea ice scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “Recovery to 1980s levels would take thickening of the ice, as well as a greater expanse.”

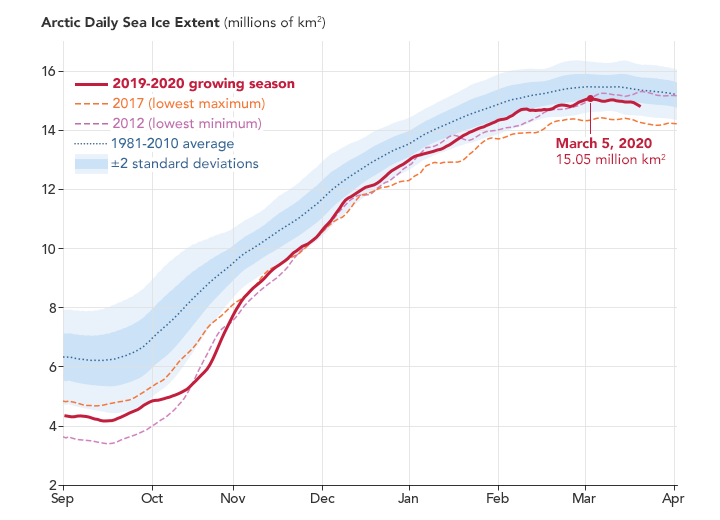

Every year, the cap of frozen seawater floating on top of the Arctic Ocean and neighboring seas melts during the spring and summer and grows in the fall and winter. The ice reaches its annual maximum extent sometime between February and April. In 2020, sea ice reached its annual maximum extent on March 5, when satellites observed it spread across 15.05 million square kilometers (5.81 million square miles).

The map above shows the ice extent—defined as the total area in which the ice concentration is at least 15 percent—at its 2020 maximum. While this maximum was largest since 2013, it remained 590,000 square kilometers (230,000 square miles) below the average maximum for the 1981-2010 period (yellow line). The lowest maximum extent on record occurred on March 7, 2017, when it measured 14.42 million square kilometers (5.57 million square miles).

Jennifer Francis, a scientist from the Woods Hole Research Center who studies the changing Arctic, noted that there can be great variability from year to year because of fluctuations in weather and ocean currents. This year, a strong stratospheric polar vortex helped trap cold air in the Arctic. The same phenomenon left mid-latitudes warmer and generally less snowy than normal.

“This winter happened to have an upswing in the ice cover, but it’s still well below normal and there’s every reason to expect the downward trend will continue,” Francis said. The downward trend is clear when you chart successive seasonal ups and downs as measured by satellites over four decades: the annual maximums and minimums are generally becoming smaller over time. This change, while seemingly remote and regional, has global consequences.

“What happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic,” Francis said. “Losing so much bright, white ice means the Earth now absorbs much more of the Sun’s energy, rather than reflecting it back to space. This amplifies the warming effect of increasing greenhouse gases by 25 to 40 percent.”

On the other side of the planet, the opposite seasonal cycle just concluded with the end of summer. Sea ice around Antarctica reached its annual minimum extent on February 20-21, 2020. The map above shows the extent of sea ice around Antarctica on February 21 as measured by satellites. Sea ice that day measured 2.69 million square kilometers (1.04 million square miles)—continuing a recovery observed in recent years, but still below the 1981-2010 average.

“The Antarctic sea ice coverage continues the small rebound that it has experienced since its precipitous decline from 2014 to 2017,” Parkinson said, “although it is nowhere close to rebounding to its record high 2014 expanse.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using data from the National Snow and Ice Data Center. Story by Kathryn Hansen.