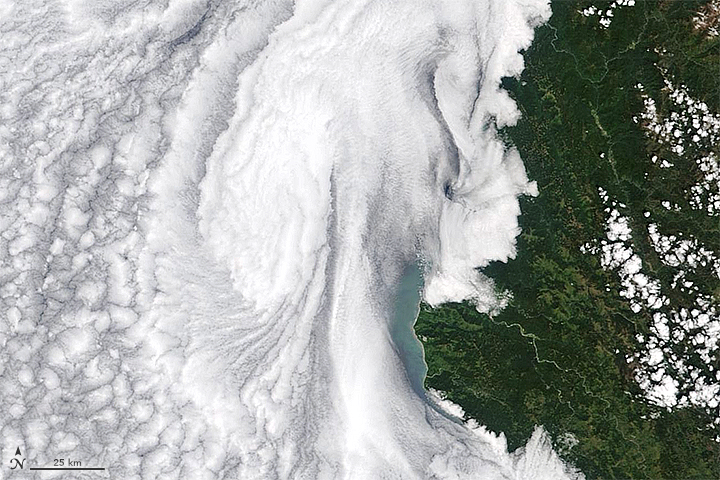

When it comes to satellite views of Earth, closer is not always better. This wide view, acquired on May 13, 2018, with the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite, captures myriad, large-scale swirls hugging the coastline of the western United States.

Off the coast of Washington and Oregon, the swirls show up in the waters of the Pacific Ocean. According to Angelicque White, a marine biologist at Oregon State University, the brown-green color near the Columbia River is likely to be stirred-up sediment. Some of the color also might be due to phytoplankton, though White notes that direct measurements made between May 14–18 turned up low levels of chlorophyll—a proxy measurement for the floating, microscopic plant-like organisms. For comparison, check out this image from July 2014 to see what a massive bloom of phytoplankton looks like.

Near California, the ocean becomes obscured by an expanse of stratocumulus clouds. These clouds form in the atmosphere’s marine layer, which extends from the ocean surface up to an altitude between 1000-2000 feet. The layer generally forms near the West Coast in spring and summer during periods of upwelling—that is, when surface waters, displaced by the wind, are replaced by cold, nutrient-rich water from the depths. When this image was acquired, winds from the northwest had moved over the water surface and mixed the moist surface air upwards to form clouds near the upper boundary of the marine layer.

Notice the vortices in the clouds near Cape Blanco and Cape Mendocino. According to Mel Nordquist of the National Weather Service in Eureka, California, the prominent headlands are partly responsible for these eddies. Air flowing from the northwest is forced up and around these land masses, forming an area of low pressure downwind. As a result, air from the south moves northward toward the area of low pressure and the headlands.

“When you put these two motions together, you get circulations or eddies that form and then peel off, moving downwind over time,” Nordquist said. “Sometimes, when conditions are just right, the eddy will stay in place and just spin just downwind of the cape.”

View this animation to see the motion of a coastal eddy that formed in May 2017. These features can form any time of year, but they are most common in the warm season. Nordquist noted: “Many times these circulations can be present, but there are no clouds so we don’t see them in visible satellite imagery.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using MODIS data from LANCE/EOSDIS Rapid Response. Story by Kathryn Hansen.