The Russian settlement of Surgut lies on the north bank of the Ob River in the cold, swampy lowlands of West Siberia. Just a small village in the 1960s, Surgut has ballooned into a bustling city of 340,000 people, largely because of the development of the vast gas and oil reserves in the area.

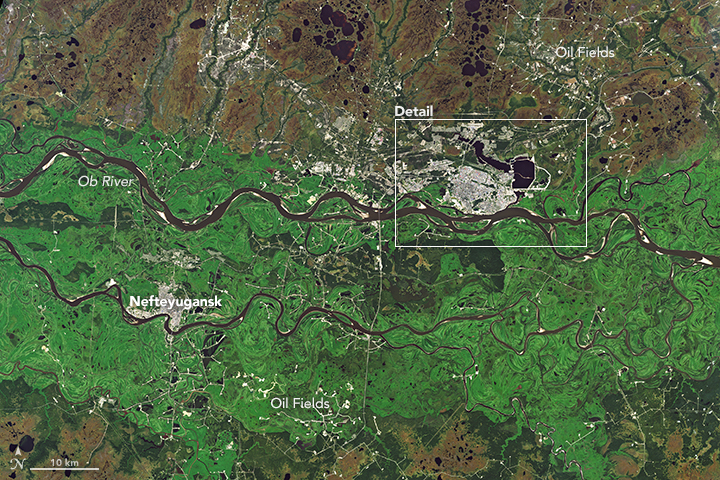

The Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 collected this natural-color image of the city and its surroundings on August 22, 2016. Gas and oil infrastructure spreads across marshlands northeast of the city, and there is another sizable oil field southeast of the neighboring city of Nefteyugansk.

Over the past two decades, NASA satellites have collected observations of the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI)—the “greenness” or health—of the vegetation in the forests and marshlands around the city. Taiga forests (light green) made up of evergreen and deciduous trees grow in the well-drained soils along the Ob River, while marshlands (light brown) with few trees dominate the swampy landscape beyond the river valley.

By analyzing NDVI measurements collected between 2000 and 2016, Igor Ezau and Victoria Miles of Norway’s Nansen Environmental Remote Sensing Center have identified some interesting changes in this area. Most notably, the taiga forests across the northern part of West Siberia have gradually become less green, a trend the scientists attribute to rising summer temperatures.

However, the opposite is true in pockets of forest around the towns and cities. When the researchers focused on changes to the vegetation within 40-kilometers (25-miles) of 28 cities in Siberia, they found the vegetation had gotten slightly greener (or browned less) than the rest of the region.

The effect was particularly pronounced around older cities like Surgut, which have had more time to establish parks and other green spaces to reverse the initial loss of vegetation cover associated with development and urbanization. In the NDVI variability map above, the cities and rivers showed low variability between 2000 and 2016 in comparison to the ring of vegetation surrounding the two cities. The greater variability indicates an increase in greening during the warmer months. Note: to generate the NDVI map, the scientists applied a statistical technique that extracted the local effects from the regional trends.

The greening trend was driven by other factors, as well. For Surgut and several other cities, development required covering swampy soils with relatively sandy, well-drained soil that was sturdy enough to build on. The sandier soils were not only better for infrastructure, they made it easier for trees to thrive.

Building materials like concrete and asphalt also created an urban heat island that increased land surface temperatures in the city core compared to rural areas around it. In the Arctic, heat islands warm the soil, which can thaw underlying permafrost and have far-reaching effects on tundra and taiga landscapes. In areas like Surgut with cool and short summers, the added warmth gives many types of vegetation a boost.

In comparison to other Siberian cities, the intensity of Surgut’s heat island is unusual. The city is home to two large gas power plants. One of them, Surgut-2, is among the largest gas-fired power stations in the world.

“Surgut is now about 10 degrees Celsius above normal, which means that ecosystems around the city have a climate that could otherwise only be found 600 kilometers to the south,” noted Ezau.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Mike Taylor and Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey and NDVI trend data courtesy of Victoria Miles/NERSC. Story by Adam Voiland.