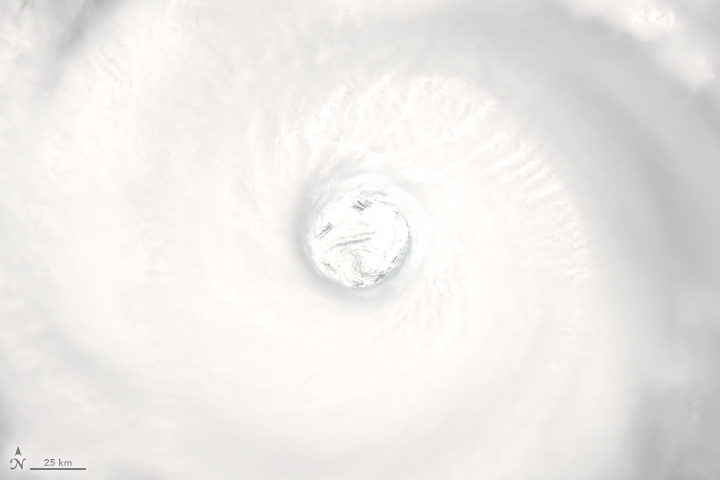

At 1:15 p.m. Japan Standard Time (04:15 Universal Time) on July 31, 2017, the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite observed Super Typhoon Noru over the western tropical Pacific Ocean. The wide view (above) shows the breadth of the storm; the second image (below) shows the details within its eye.

At the time, the center of Noru was located about 250 kilometers southwest of Iwo Jima. Maximum sustained winds measured 240 kilometers (150 miles) per hour, making it the equivalent of a category 4 storm. The typhoon had weakened somewhat since July 30, when it briefly became a category 5 storm—the strongest so far in 2017 in the northern hemisphere. Some forecasts suggest that Noru could ultimately head toward mainland Japan, but not for several days.

Last week, Noru had a sibling storm nearby in the western Pacific. Satellite imagery captured on July 24 and July 25 showed Tropical Storm Kulap appearing to move in tandem with Noru. According to Oreste Reale, a research meteorologist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, the imagery suggests that the systems were tangled in a dance known as the “Fujiwhara effect.” The phenomenon occurs when two cyclones are close enough to each other that they both rotate around a common center.

“This occurs much more often than people believe, if we watch at the low-level vorticity fields,” Reale said. Many rotating systems—not just named storms—will tend to rotate around a common center, with the stronger system pulling the weaker one toward it. Occasionally the two systems can merge, though that never happened with Kulap and Noru.

“Albeit common, the Fujiwhara effect is very unstable,” Reale said. “The two vorticity maxima must be at a certain distance and reach some sort of temporary balance. If one of the two has a drastic change—for example the lower levels become affected by drag so that the storm enters a rapid weakening—the Fujiwhara effect rapidly vanishes.”

Noru has produced some beautiful examples of typhoon structure, as revealed in a range of satellite images. Dynamic features in the eye, for example, stand out in an animation of images from Japan’s Himawari-8 satellite.

The structure appears to be typical of a strong storm, according to Scott Braun, a research meteorologist at NASA Goddard. “We’ve seen this sort of structure in other storms with large eyes,” he said. But even if the storm and its structure are not unusual, we can still appreciate the striking imagery.

NASA image by Jeff Schmaltz, LANCE/EOSDIS Rapid Response. Story by Kathryn Hansen.