A five-year drought in California ended spectacularly this winter, with the state emerging from one of its driest periods on record by enduring one of its wettest. Reservoirs, lakes, and mountainsides are now brimming with water and snow, though scientists caution that the unseen reservoirs—underground aquifers—are a long way from having the same bounty that is visible on the land surface.

A steady stream of atmospheric river events brought 175 percent of the long-term average of rain and snow to California between October 2016 and April 2017, leading the state to declare an end to the official drought emergency in all but four counties. In its April 18 update, the U.S. Drought Monitor reported just 8 percent of the state was in some form of drought and 23 percent was abnormally dry (almost entirely in southern California). One year ago, 91 percent of the state was in drought, with 55 percent at extreme or exceptional status. As recently as December 27, 2016, the Drought Monitor reported 82 percent of the state in some measure of drought.

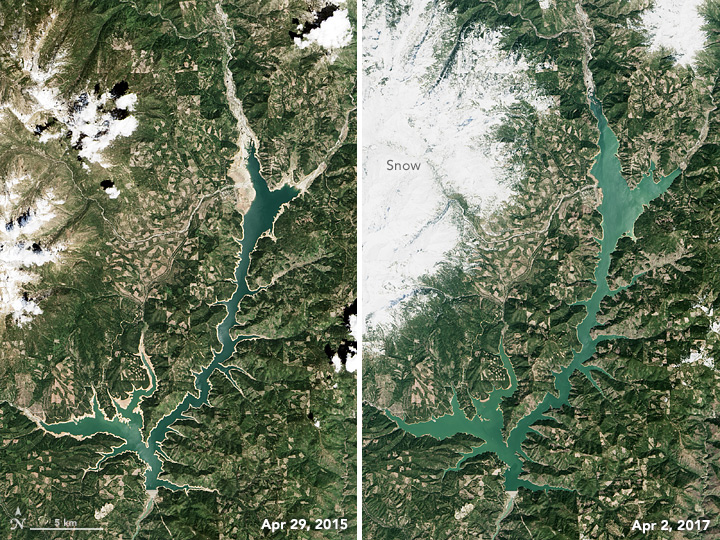

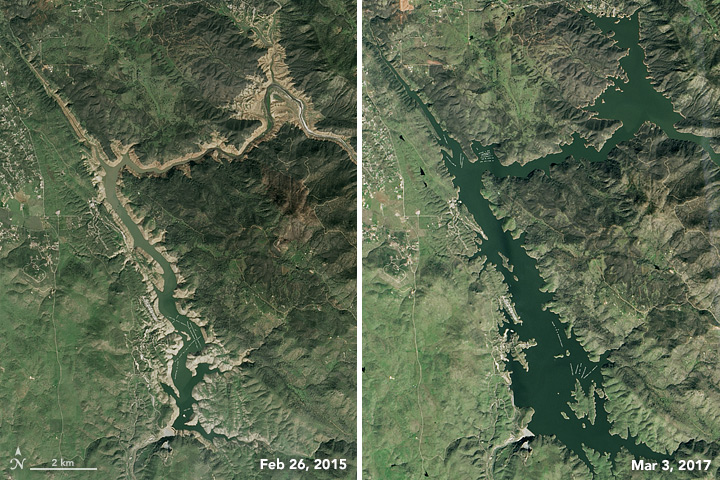

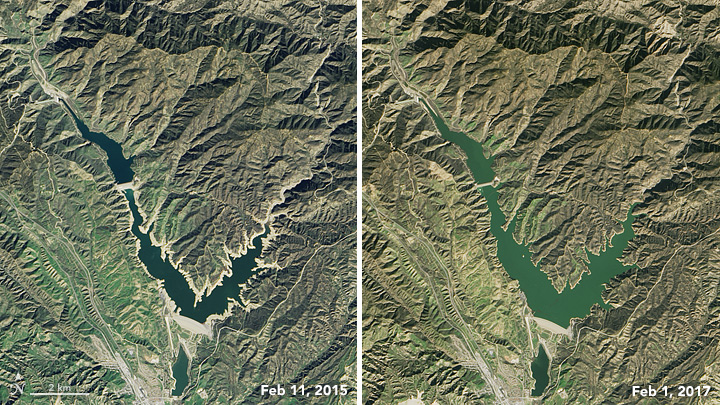

These six satellite images show key reservoirs in California near their lowest and highest points over the past three years. All images were acquired by the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8. The image pairs were chosen to match seasons and to avoid cloud cover over each scene. Tan bands around the shorelines (left image in each pair) are sands and sediments that were exposed as water levels dropped and the lake bottom became exposed. Note that changing water levels largely reflect precipitation and evaporation, but they also can be altered by the movement of water between reservoirs and water transportation infrastructure in the California water system.

The images at the top of the page show Trinity Lake, the third largest reservoir in the state (after Lake Oroville and Shasta Lake). The artificial lake in northern California connects to the Trinity River and is part of the Sacramento basin. On April 29, 2015, Trinity stood at 59 percent of its historical average level for that date; by April 2, 2017, it stood at 114 percent. As of April 19, the lake was filled to 95 percent of its 2.45 million acre-foot capacity (and 117 percent of average water levels).

Don Pedro Reservoir, California’s sixth largest, stands in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada and connects to the Tuolumne River and the San Joaquin Valley Basin. It is just miles from New Melones Lake, which is visible in the downloadable large image. When Landsat 8 acquired an image on February 26, 2015 (above), the reservoir stood at 61 percent of its long-term average level. By March 3, 2017, it had risen to 134 percent of average.

The third image pair (below) shows Castaic Lake, which is the 24th largest reservoir in California but the largest water storage in the Los Angeles area. It stood at just 42 percent of average water levels on February 11, 2015; by February 1, 2017, it was back up to 98 percent.

The California Department of Water Resources, which tracks 46 major reservoirs, reported on April 18, 2017, that water storage stood at 112 percent of the long-term average for the entire system. Click here for an interactive tool showing water levels across the state by date.

“Reservoirs at the surface are only a partial measure of California’s water health,” cautioned Bill Patzert, a climatologist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “From space, it looks like we are out of five years of punishing drought. But the depleted aquifers, 100 million dead trees, and $1 billion in flood damage will take decades to deal with.”

Scientists at JPL are leading NASA-wide efforts to better study water storage and precipitation, alongside research partners in the California government and academic research community. The projects, known as the Western States Water Mission and the Western Water Applications Office, are working to make high-resolution satellite and aircraft data, as well as climate and hydrology models, more readily available to civic leaders in the region.

“Drought or deluge, we use more water than we have, and California suffers from chronic water scarcity,” said Jay Famiglietti, a hydrologist at JPL who leads the applied research effort. “That’s because California grows virtually all of the produce for the United States, as well as a tremendous amount of dairy. That level of productivity simply requires more water than is available on an annual renewable basis (snowmelt, rivers, and reservoirs). The water shortfall comes from groundwater, and that groundwater has been in decline for nearly a century. This winter will provide a slight replenishment bump, but that’s it.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Jesse Allen, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Mike Carlowicz.