It may look like someone dyed the water green for St. Patrick’s Day, but the green hue visible off the coast of Antarctica is entirely natural.

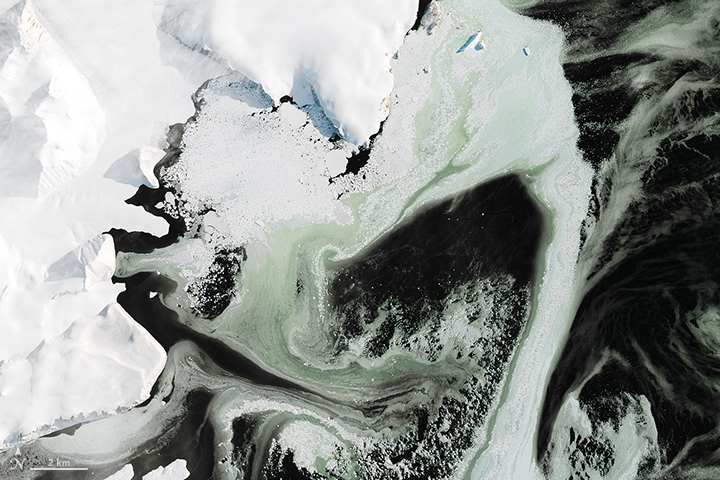

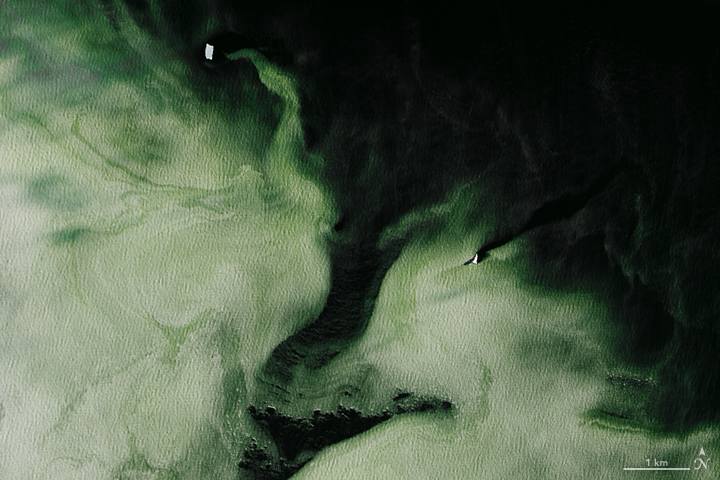

On March 5, 2017, the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 captured these natural-color images of water, sea ice, and phytoplankton. The region pictured is Antarctica’s Granite Harbor—a cove in the vicinity of the Ross Sea. The first image shows a wide view of the area, and the subsequent images show detailed views of the green slush ice.

Jan Lieser, a marine glaciologist from Australia’s Antarctic Climate and Ecosystems Cooperative Research Center thinks the green color is caused by phytoplankton at the water’s surface that have discolored the sea ice. These microscopic marine plants, also called microalgae, typically flourish in the waters around Antarctica in the austral spring and summer, when the edge of the sea ice recedes and there is ample sunlight. But scientists have noticed that given the right conditions, they can grow in autumn too.

Lieser and colleagues previously observed late blooms in 2012 off East Antarctica’s Princess Astrid Coast. Blooms around the continent that year were later confirmed by measurements from a research ship. In fall 2015 and again in 2017, phytoplankton have turned up in Terra Nova Bay—just south of the Granite Harbor location pictured here.

Sea ice, winds, sunlight, nutrient availability, and predators all factor into whether plankton can grow in large enough quantities to color the slush-ice and make it visible from space. In early 2017, there was not much ice anchored to the shoreline (fast ice), a condition that is thought to help “seed” phytoplankton growth. But offshore winds and sunlight favorable for growth made conditions similar to previous years that supported blooms, according to Lieser.

Scientists know that phytoplankton are important for the ecology of the Southern Ocean, as they are an abundant food source for zooplankton, fish, and other marine species. But researchers still have many questions about their presence around Antarctica in the fall. Lieser wonders: “Do these kinds of late-season ‘blooms’ provide the seeding conditions for the next spring’s bloom? If the algae get incorporated into the sea ice and remain more or less dormant during the winter, where do they end up after the winter?”

Scientists might get some answers from an expedition scheduled to visit the area in April 2017.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Caption by Kathryn Hansen.