At first glance, a river’s course may seem fixed and unchanging. In truth, the path is a perpetual work-in-progress that, in some cases, can shift dramatically in a short span of time.

This is especially true in the Moxos plains of northern Bolivia. In this tropical area east of the Andes, several rivers meander through a swampy landscape of savanna, forests, and ponds. While studying three decades of satellite imagery of this area, geographer Umberto Lombardo of University Pompeu Fabra noticed a particularly striking example of rapid change on a stretch of the Maniqui River.

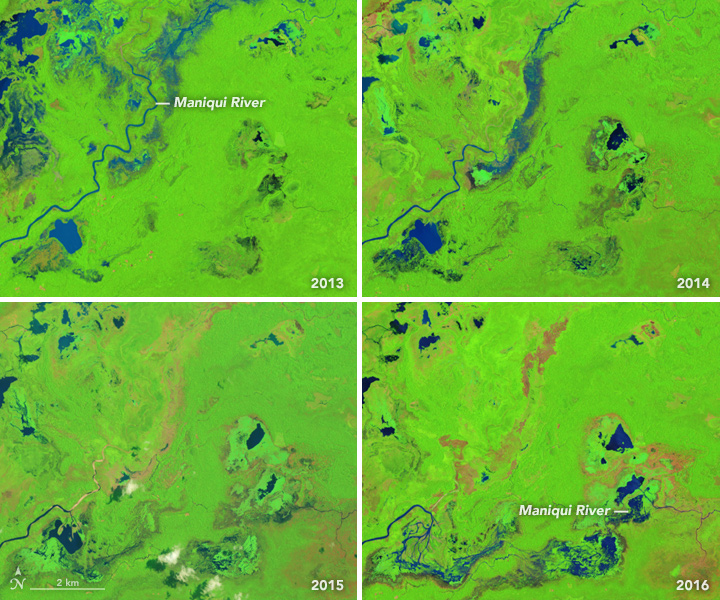

The Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 captured four false-color images between 2013 and 2016. These images were assembled using red, green, and shortwave infrared light. The use of infrared light makes it easier to distinguish between silt-laden water and bare land. Water absorbs infrared light, while plants and bare earth reflect it. As a result, areas with standing water appear blue, while bare land appears light brown. Forests are bright green; savanna is pink-brown.

The image on the upper left shows the course of the river in September 2013, when it flowed in a northeasterly direction. By August 2014, it had broken through its right bank and began to spill into a swampy depression nearby. By September 2015, the river had broken out of its channel for a second time, this time flowing into a pond a few kilometers south of the first break. By July 2016, sediment deposited by the river had filled in most of the pond and the river was charting a more easterly path. Over those three years, vegetation growth started to cover up the channel that was full of water in 2013.

“Images like this underscore how much and how quickly small- and medium-size rivers in this part of the world change,” said Lombardo. Earlier research on larger rivers in the Amazon had suggested that big shifts in a river’s path usually coincide with major flooding associated with La Niña, a cyclical cooling of ocean temperatures in the equatorial Pacific. But after systematically combing through three decades of satellite imagery and the paths of 12 small and medium-sized rivers in the southern Amazon, Umberto found no obvious connection to La Niña. Instead, he found that the course of small rivers tended to be in a regular state of change regardless of La Niña cycles.

Umberto’s findings have on-the-ground implications. Authorities should be prepared for the possibility that indigenous communities living along small rivers may have to be resettled if rivers shift in the coming years. Also, a planned road linking Villa Tunari to San Ignacio de Moxos may be destroyed or regularly flooded without careful planning, he explained.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Jesse Allen, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Caption by Adam Voiland.