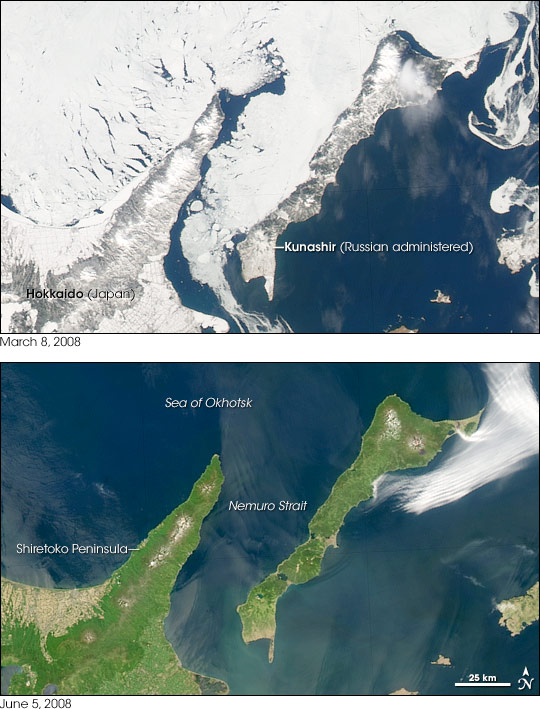

This wintry scene of a frozen ocean and snow-covered land may not seem remarkable until you note that the Shiretoko Peninsula is at the same latitude (44 degrees North) as central Oregon on the other side of the Pacific Ocean. The U.S. cities of Portland and Seattle are both farther north, and neither experience the harsh winter illustrated in this image. The Shiretoko Peninsula of northern Japan became a United Nations World Heritage Site in 2005 because it is the southernmost point at which sea ice routinely forms in the Northern Hemisphere. The seasonal ice supports a rich and unique ecosystem.

The Sea of Okhotsk owes its seasonal swings to its geography. The Russian-administered Kurile Islands shelter the sea from the currents of the open Pacific Ocean to the east, while the islands of Japan block warm currents from the south. This limits the circulation of warm water through the sea. At the same time, the Amur River pours fresh water into the Sea of Okhotsk. The fresh water remains trapped in the top 50 meters (165 feet) of the sea by a layer of dense, cold, salty water. Winter brings frigid temperatures from Siberia, and the relatively fresh water near the sea’s surface freezes quickly.

On the other side of the pendulum is the ice-free and snow-free landscape of summer, shown in the lower image. Warm summer currents and a warm summer sun melt the ice, revealing open water and a green, forest-covered landscape. From the coast to the tree line, 90 percent of the Shiretoko Peninsula is covered with pristine vegetation ranging from a cool, broadleaf forest near the coast to an alpine coniferous forest in the mountains that run up the center of the peninsula. The bare, rocky mountain tops are above the tree line and are tan in this photo-like image.

This wilderness is an oasis for wildlife. During the winter, ice algae grow in the mineral-rich waters under the ice. As the ice melts, other forms of phytoplankton flourish. The highly productive waters sustain a diverse and thriving ecosystem. According to the United Nations, the phytoplankton and the zooplankton that eat the phytoplankton are at the base of the food chain for 28 species of marine mammals and 223 species of marine fish. Since the region depends on the annual sea ice, it is particularly prone to global warming.

The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite captured these images on March 8, 2008, top, and June 5, 2008, bottom.

NASA images by Norman Kuring, MODIS Ocean Color Team. Caption by Holli Riebeek.