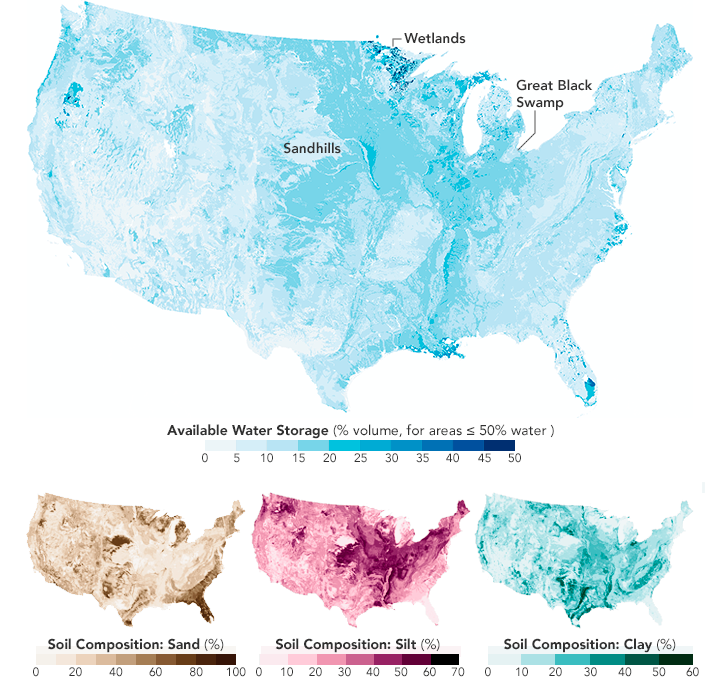

Soil is the sum of its parts. The most basic ingredients include sand, silt, and clay of various particle sizes, as well as rock fragments, roots, live organisms, air, and water. But depending on your location, the proportion of those ingredients can vary dramatically.

Farmers and gardeners are particularly interested in soil composition because it affects the amount of water stored in the soil that is available to plants, or the “available water capacity.” Soils with more sand tend to drain water faster than soils with more clay, while soils with more silt tend to have intermediate drainage properties.

The maps above show this relationship between soil type and the volume of available water storage. The maps are based on a dataset of soil characteristics for the conterminous United States, or “CONUS-Soil,” developed by Douglas Miller and Richard White of Penn State. The data are described in detail in the journal Earth Interactions.

“Some of the neatest things that I think CONUS-Soil shows are large-scale features in the landscape,” Miller said. “One of the most striking of these is the Nebraska Sand Hills.” The composition maps show this part of Nebraska to have a high percentage of sand (dark brown), little silt (light pink), and little clay (light teal). According to Miller, these ancient sand dunes are now covered with vegetation and stabilized. Due in part to the high sand content, water in this area is a precious resource—evident in the top map as a broad area where the available water storage is low (light blue).

Minnesota, on the other hand, has a unique, variable landscape affected by past glaciation. Informally called the “land of 10,000 lakes,” the state’s numerous wetlands have high clay content that more easily retains water. “But glaciers tend to leave a landscape that has high variability,” Miller said, “hence the pattern that you see in the maps.”

Another interesting feature shows up around Toledo, Ohio, and Lake Michigan. The area once known as the Great Black Swamp was drained by settlers in the mid 1800s. “If you return to that area today, however, you would discover that the soils still tend to hold water,” Miller said. “In order to keep farming the area, the soils must be continuously drained.”

Read more in our feature story: A Little Bit of Water, A Lot of Impact.

NASA Earth Observatory maps by Joshua Stevens, using data from the CONUS-SOIL database by Miller, D. A., & White, R. A. (1998). Caption by Kathryn Hansen.