In California and other states, snowfall is critical to fresh water supplies. In the mostly arid climate west of the Rockies, snow cover laid down on the mountains in winter is a liquid checking account that is usually drawn down each summer and fall when rainfall is sparse. As California heads into another year of drought, the snow-white bank account in the mountains is unusually low on funds.

The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite captured two natural-color images of the snow cover in the Sierra Nevada in California and Nevada. The top image was acquired on March 27, 2010, the last year with average winter snowfall in the region. The second image was acquired on March 29, 2015. In addition to the significantly depleted snow cover, note the change of color in the Central Valley of California and the lack of snow in the interior of Nevada. (Most of the white in 2015 is cloud cover.)

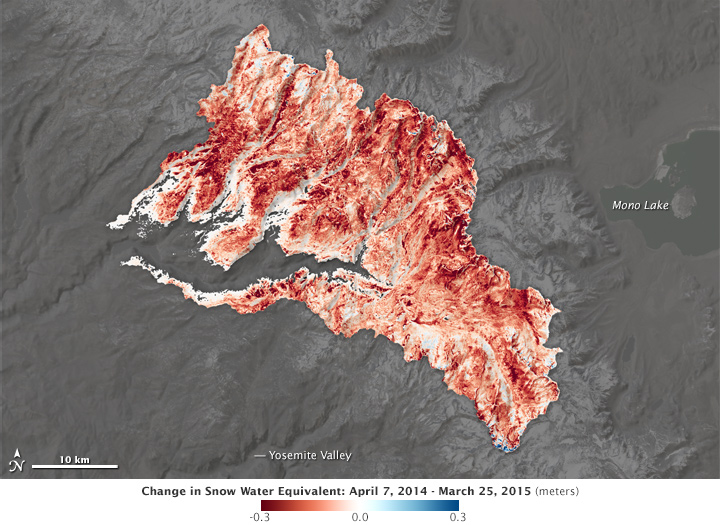

Looking closely at the Tuolumne River Basin in the Sierra Nevada, scientists working with NASA’s Airborne Snow Observatory (ASO) found the snowpack there contained just 40 percent as much water in 2015 as it did at its highest level in 2014—which was already one of the two driest years in California’s recorded history. In its first springtime acquisition of 2015, the ASO team quantified the total volume of water contained in the basin: On March 25, the mountain snowpack was 74,000 acre-feet, or 24 billion gallons. In the same week of 2014, the snow total was 179,000 acre-feet.

The third image is a difference map showing the snow-water equivalent in the Tuolumne River Basin from late March 2015 versus early April 2014. Snow-water equivalent is a measure of the total volume of water in the snowpack. Red areas had significantly less water in March 2015, while blue areas had more.

The Tuolumne Basin is a water supply for the Turlock and Modesto irrigation districts and the Hetch Hetchy Regional Water System, which serves San Francisco and neighboring communities. This is the third year of Airborne Snow Observatory operations, and the group works in partnership with the California Department of Water Resources, the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission and the Turlock and Modesto irrigation districts.

In normal years, snowfall supplies about 70 percent of California’s annual precipitation, melting in the spring and early summer. The greater the snowpack water content, the greater the likelihood California’s reservoirs will receive ample runoff to meet the state’s water demands in the summer and fall.

Tom Painter, who leads the snow observatory team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said the ASO data give water managers near-real-time information on how much water they can expect to flow from the mountains during California’s ongoing drought, now in its fourth and most intense year. “A mountain’s snowpack is like a giant TV screen, where each pixel in the image varies but blends together with the others to make up a picture,” said Painter. “For the past century, we’ve estimated mountain snowpack by looking at just a few pixels of the screen—that is, a few sparse ground measurements in each watershed basin. During an intense drought like this one, most of the pixels on the screen are blank; they’re snow-free. NASA’s Airborne Snow Observatory is able to measure the snowpack in every pixel of the screen that still has snow, and put together a complete picture of how little actual snow there is.”

“It looks from our snow courses and pillows that statewide, we have about half or less of the lowest April 1 snowpack on record,” said Frank Gehrke, chief of the California Cooperative Snow Surveys. “ASO data on snow water volume don’t represent newly-found water; rather, they provide a new ability to inform our constituents how much water is there and how its volume is changing week to week.”

As of April 1, 2015, four of six snow pillows in the Tuolumne Basin were lacking snow. Across California, 88 of the 123 total snow pillows are snow-free. Normally at this time of year, snow accumulations are at their peak, and the vast majority of these pillows still have snow.

“This information is being used to improve modeling estimates of future water runoff,” said Hetch Hetchy Reservoir operator Adam Mazurkiewicz. “Improvements in runoff forecasting will guide more efficient system operations and water usage, not just in the drought years that we are currently experiencing, but also in future times of flooding and even normal conditions.”

The Airborne Snow Observatory combines a scanning lidar instrument with an imaging spectrometer flown aboard a King Air aircraft to measure snow depth and reflectivity of the snowpack across several mountain basins in the Sierra Nevada and Colorado River Basin. From airborne measurements of snow depth, plus ground-based measurements and modeling, researchers can derive the volume of water in the snowpack. The reflectivity of the snow—that is, how bright or dirty the snowpack is—provides information on how fast it will melt as darker snow absorbs more solar radiation.

Click here to see the Airborne Snow Observatory maps, which are updated weekly.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Jesse Allen, using data from the Level 1 and Atmospheres Active Distribution System (LAADS). Caption by Alan Buis and Michael Carlowicz.