Brazil is a leading exporter of soybeans, a primary source of animal protein feed around the world and the second largest source of vegetable oil. Demand for soybeans has been growing for several decades, leading to the expansion of production in and around the Amazon rainforest. In an effort to “reconcile environmental preservation with the region's economic development,” growers and traders signed a moratorium in July 2006 to avoid production of soybeans on newly deforested Amazon rainforest. (Purchases of soy grown on land cleared before 2006 remain permissible.)

New research by university and NASA scientists suggests that deforestation of the Amazon for soy production has declined under the moratorium. However, as the moratorium was only applicable to the Brazilian Amazon, a very different scenario has been playing out in neighboring savanna-woodland areas known as Brazil’s Cerrado.

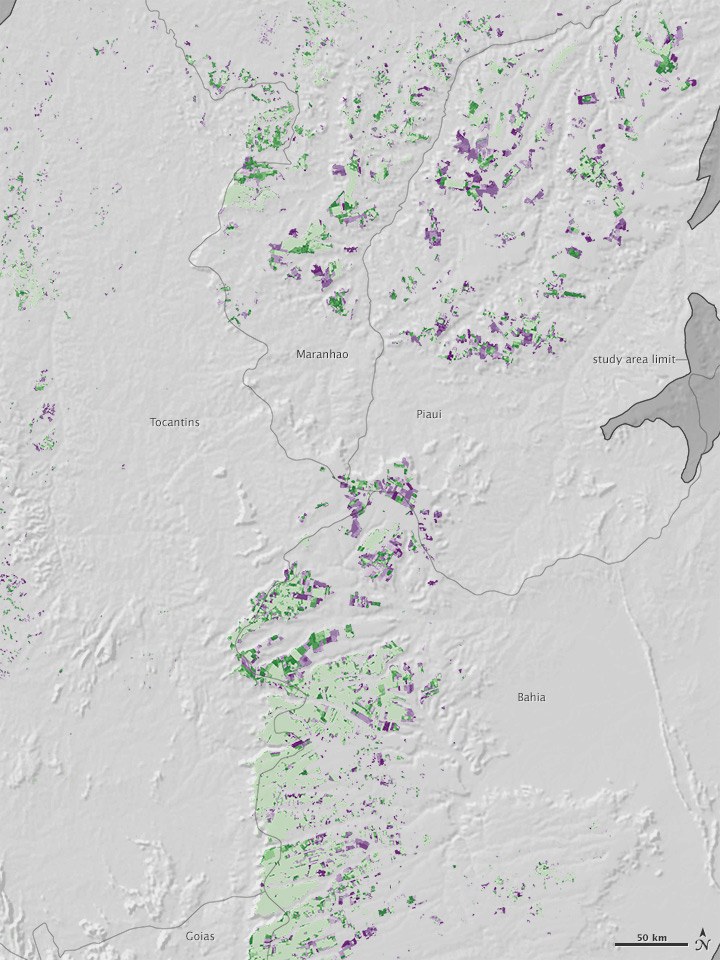

The map above, based on data from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite, shows the expansion of soy production across the Cerrado. Green represents areas cleared before the Amazon moratorium (2001-2006), and purple represents areas cleared while the moratorium was in effect (2007-2013).

Soy expansion between 2001 and 2006 largely occurred as infilling around farms that already existed in 2001 (light green). After 2006, the new frontiers for soy production appeared in Mapitoba—an eastern subregion within the Cerrado and a recent hotspot for agriculture—as well as in the Araguaia River basin and portions of Mato Grosso do Sul.

“Looking at the dynamics of soy expansion in the Cerrado region provides a more complete picture of changes before and after the Amazon’s moratorium,” said Doug Morton, NASA scientist and co-author of the recent paper published in Science. “Although Cerrado regions are not covered by the moratorium, environmental laws still require set-aside areas of native vegetation. Forest cover losses in the Cerrado partially offset declining deforestation rates in the Brazilian Amazon.”

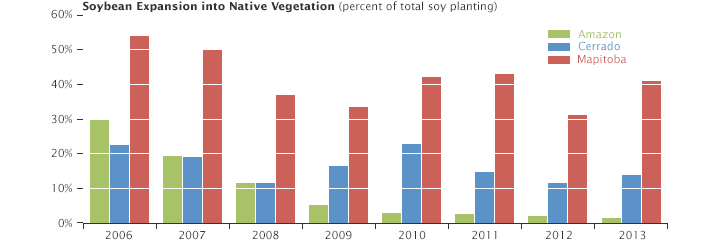

The magnitude of the change is apparent in the bar chart above. At the start of the moratorium, about 30 percent of soy expansion in the Amazon (green bars) was achieved by cutting down Amazon forests. By 2013, that number dropped to about 1 percent as farmers transitioned to growing soy on previously cleared land.

Without a corresponding moratorium, 11 to 23 percent of new farmland cleared each year for soy in the Cerrado (blue bars) was carved out of natively vegetated land. The expansion was even more widespread in Mapitoba (red bars), where that number hovered around 40 percent.

The map above shows a close-up of Mapitoba, an acronym for the confluence of four states: Maranhão, Piauí, Tocantins, and Bahia. The data reveal the field-by-field clearing of land for soy in the region. Morton says that more research is needed to determine whether the moratorium in the Amazon contributed to clearing of land in the neighboring Cerrado—a so-called “leakage effect.”

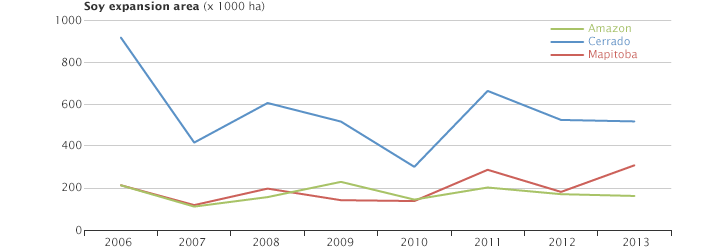

Morton believes growers in the Cerrado could replicate the success of the Amazon moratorium. The line graph above shows that the Amazon’s soy-farming areas actually increased by 1.3 million hectares during the moratorium period—growth that was achieved by growing the crop on existing pasture or already cleared land.

“Intensifying agricultural production on existing cleared areas is seen as a win-win strategy,” said Morton, “increasing outputs while safeguarding habitat and minimizing greenhouse gas emissions from land cover change.”

Yet soy expansion is part of a complicated regional development puzzle. “To be effective, the soy moratorium must be replicated in other sectors, such as beef and leather, and in neighboring biomes,” Morton said. “Otherwise, soy may simply displace other land uses further into the forest.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Jesse Allen, using data provide by Douglas Morton and Praveen Noojipady (NASA/GSFC). Caption by Kathryn Hansen