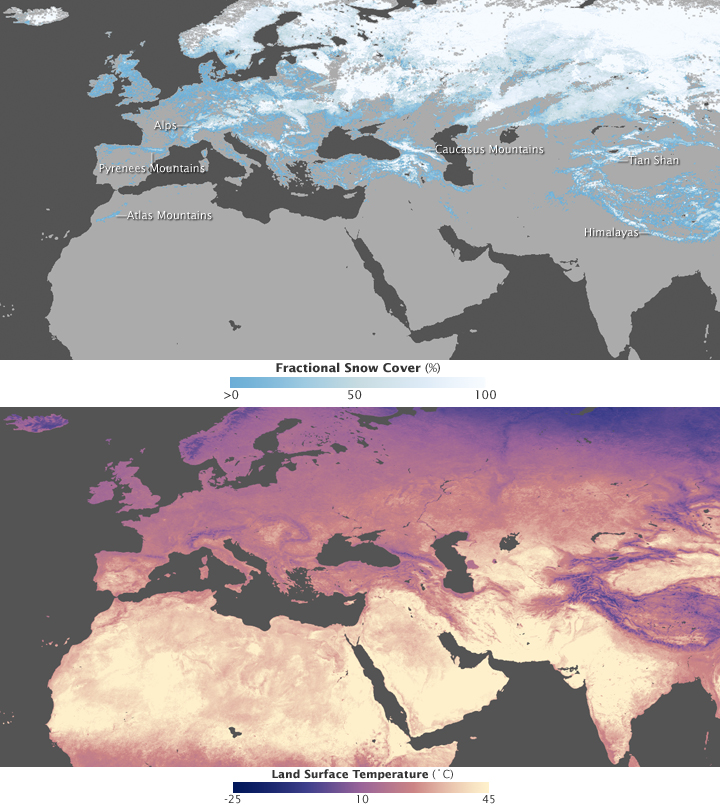

How cold and snowy will it get this winter? Though many things control temperature and precipitation patterns, the answer to that question largely depends on where you live. As these images show, latitude and elevation are the primary influences on whether you will have a cold and snowy winter. These images show snow cover (top) and daytime land surface temperature (bottom) as observed by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) flying on NASA’s Terra satellite between November 1 and December 1, 2007.

Snow cover and land temperature are connected, but one does not necessarily cause the other. Snow certainly influences how hot or cold the land feels to the touch, and land temperature influences whether or not snow remains on the ground or melts away. But the most obvious global pattern these images demonstrate is not the effect of temperature and snow cover on each other, but the effect of latitude and elevation on each. In general, the farther from the equator an area is, the colder and snowier it will be. This is because higher-latitude regions receive less light and energy from the Sun than low-latitude, tropical areas. Imagine spaying a beach ball with a jet of water. The most water will hit the ball in the center of the stream, but water from the edge of the stream will flow around the top and bottom of the ball. In the same fashion, direct light from the Sun hits the Earth’s center, while the poles at either end of the globe receive a smaller portion of the Sun’s light.

The land surface temperature image, which includes Europe and most of Asia in the Northern Hemisphere, shows how the indirectness of sunlight at high latitudes affects temperature. The coldest areas, colored blue and white, are in the north, while the warmest areas, yellow and red, are near the Equator. These are also the planet’s most snow-covered areas. Areas that were entirely covered in snow during at least part of November 2007 are solid white, while snow-free areas are solid green. Not surprisingly, the most snow was on the ground in the far north where temperatures were coolest.

Latitude is not the only thing that influences temperature and snow cover. Arcs of cold blue and snow cut across otherwise warm, snow-free areas in Asia, Europe, and Africa. These seemingly out-of-place cold areas are mountain ranges. The Alps curve across the boot-shaped Italian peninsula like a cuff; the Pyrenees separate Spain and France; a single line of snow in northern Africa follows the Atlas Mountains; the Caucasus Mountains connect the Black and Caspian Seas in western Asia; and the Himalaya and the Tian Shan form an oval in central Asia. Higher elevations are cooler than lower elevations because of adiabatic heating. When a parcel of air moves from a low elevation to a high elevation, it expands because it is under less pressure. It has less weight pressing down on it from the air above it. As the air expands, its temperature drops. The cool air temperature freezes precipitation, and snow falls instead of rain. The cold air also cools that ground so that, when snow falls, it is more likely to accumulate than to melt. A comparison of the land surface temperature and snow cover images to a topographic map reveals that temperatures tend to be coolest and snow cover greatest at high elevations such as mountains.

These images are from the NEO (NASA Earth Observations) web site, which provides daily, eight-day composite, and monthly composite images of a variety of global measurements, including land surface temperature and snow cover. NEO also provides tools that make it easy to compare and analyze Earth observation data.

NASA images produced by Reto Stockli, NASA’s Earth Observatory Team, using data provided by the MODIS Land Science Team.