The ravages of deforestation, wildfires, windstorms, and insects on global forests are revealed in unprecedented detail in a new study based on data from Landsat satellites. Researchers developed new mapping tools that are the first to document forest loss and gain at high resolution and with a consistent method around the globe.

The maps will allow scientists to compare forest changes in different countries and to monitor annual deforestation. Since each pixel in a Landsat image shows a 30-meter square of land—an area about the size of a baseball diamond—researchers can see enough detail to tell local, regional, and global stories.

University of Maryland researcher Matthew Hansen and colleagues analyzed 143 billion pixels in 654,000 Landsat images to compile maps of forest loss and gain between the years 2000 and 2012. Key to the project was a collaboration with a team from Google Earth Engine, who took the models developed at the University of Maryland for processing and characterizing the Landsat data and reproduced them in the Google Cloud. Years of data processing was reduced to days.

Across the study period, 2.3 million square kilometers (888,000 square miles) of forest were lost, and 800,000 square kilometers (309,000 square miles) had new growth. In that time, Brazil actually cut its deforestation rate from approximately 40,000 square kilometers (15,400 square miles) per year to 20,000 square kilometers (7,700 square miles) per year. “That's the result of a concerted policy effort to reduce deforestation,” Hansen said, “and it sets a standard for the rest of the world.”

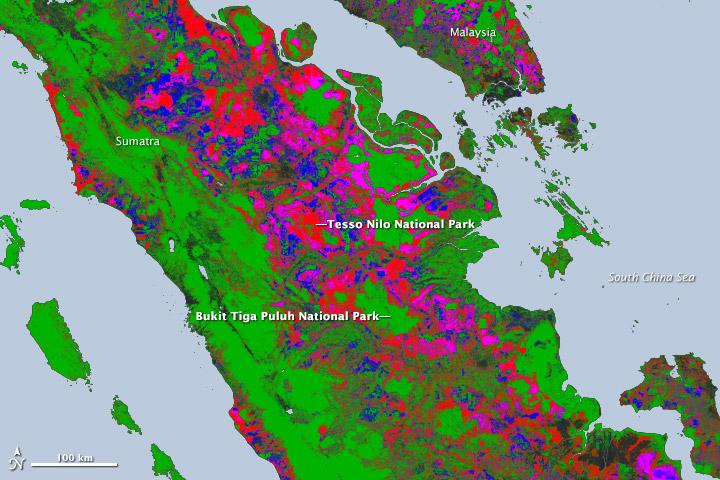

The team found that the deforestation rate in other countries increased. Indonesia’s deforestation rate doubled from approximately 10,000 square kilometers (3,900 square miles) per year in 2000–2003 to more than 20,000 square kilometers (7,700 square miles) in 2011–2012. The image above shows forest change data for the island of Sumatra, with red indicating forest that has been cleared, blue depicting new growth, and purple representing areas were trees were both cut down and re-grown. Green is untouched forest cover.

Prior to this study, country-to-country comparisons of forestry data were not possible at this level of accuracy because different countries define and monitor forests differently. “When you put together datasets that employ different methods and definitions, it’s hard to synthesize,” Hansen said. “But with Landsat, we can apply the same algorithm to forests in the Amazon, in the Congo, in Indonesia, and so on. It’s a huge improvement in our global monitoring capabilities.”

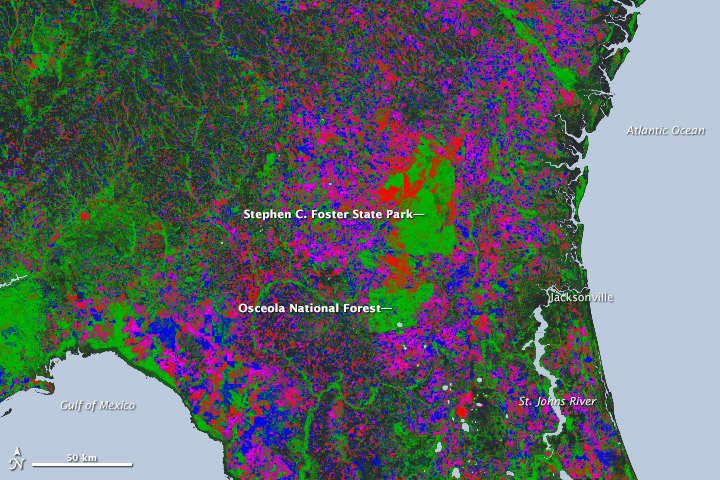

This second image shows a different pattern of change from the southeastern United States. In Georgia, northern Florida, and other southern states, landowners harvest trees for timber and quickly plant their replacements. The result is a patchwork of purple. “In this eco-region in the southeast, 30 percent of the forest land was regrown or lost during this period,” Hansen said. “It’s incredibly intensive. Trees are really treated like a crop in this region.”

“Since the first Landsat satellite launched 41 years ago, scientists have been improving their land cover analysis as computers have become more powerful,” added Jeff Masek, Landsat project scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “Projects like Hansen's took a big leap forward once USGS made the data freely available on the Internet in 2008.”

You can explore the new data set online. The research team included scientists from the University of Maryland, Google, the State University of New York, Woods Hole Research Center, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and South Dakota State University. The work was published in the November 15 issue of the journal Science.

NASA Earth Observatory map by Kevin Ward, using data from Hansen et al, the University of Maryland, and Google Earth Engine. Caption by Kate Ramsayer, NASA Earth Science News Team.