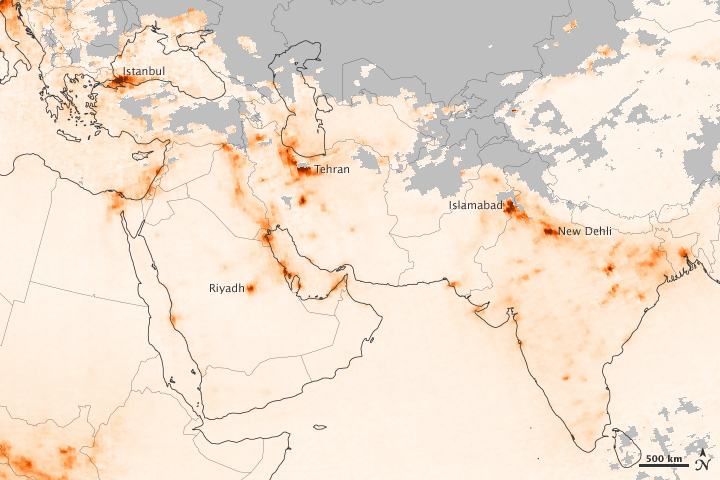

Cold winter weather and burgeoning industrial economies have made for difficult breathing in Asia and the Middle East this January. News reports from Tehran, Beijing, and other cities have described hazy skies with very low visibility; restrictions on driving, factory operations, and outdoor activity; and hospitals full of people with lung ailments.

The map above shows the concentration of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) in the atmosphere above southwestern Asia from January 1–8, 2013. Shades of orange reflect the relative abundance of NO2, while grays show areas without usable data (cloud cover, for instance). The data were acquired by the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) on NASA’s Aura satellite. OMI measures the visible and ultraviolet light scattered and absorbed by Earth’s atmosphere and surface. The presence of NO2 causes certain wavelengths of light to be absorbed.

Nitrogen dioxide is a key emission from the burning of fossil fuels by cars, trucks, power plants, and factories; the combustion of fuel also produces sulfur dioxides and aerosol particles. When the weather is hot and sunlight strongest, NO2 emissions usually lead to the creation of ground-level ozone. In the winter, NO2 is less likely to breed ozone, but it does linger for a long time and contribute to fine particle pollution. Year-round, it is a good proxy for the presence of air pollution.

Reports from Tehran and other cities note that the air is full of particulate matter, which is easier to spot from the ground but harder to measure from space. Desert landscapes, snow cover, and clouds all make airborne particles difficult to measure with nearly all current satellite instruments. Given that aerosols and NO2 usually arise from the same fuel-burning emissions, the presence of one usually indicates the presence of the other.

In winter, several trends can combine to significantly harm air quality. When the weather is cold, people burn more fuel to keep warm. In many developing economies, the most widely available fuel is coal, which can produce more particulates and smog-producing compounds than other forms of energy.

At the same time, the weather is conspiring to keep these emissions close to the ground. In most times of year, the air higher in the atmosphere is cooler than the air near the ground, allowing warm air to rise and carry pollution up and away from its source. But in the winter, temperature “inversions” can form, where the air near the ground is cooler than the air at altitude. Polluted surface air rises a bit, but then runs into warmer air masses above and stays trapped near the surface.

Winter also can bring strong high pressure systems, which generate less wind and more stable atmospheric conditions that also hold surface air in place. Even geography can concentrate the air pollution. If a city is surrounded by mountains, cold air may continually sink down into the basin and the hills may temper or redirect the winds that can clear the air.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen, using data provided courtesy of the Aura OMI science team. Caption by Michael Carlowicz.