A deep and persistent drought struck vast portions of the continental United States in 2012. Though there has been some relief in the late summer, a pair of satellites operated by NASA shows that the drought lingers in the underground water supplies that are often tapped for drinking water and farming.

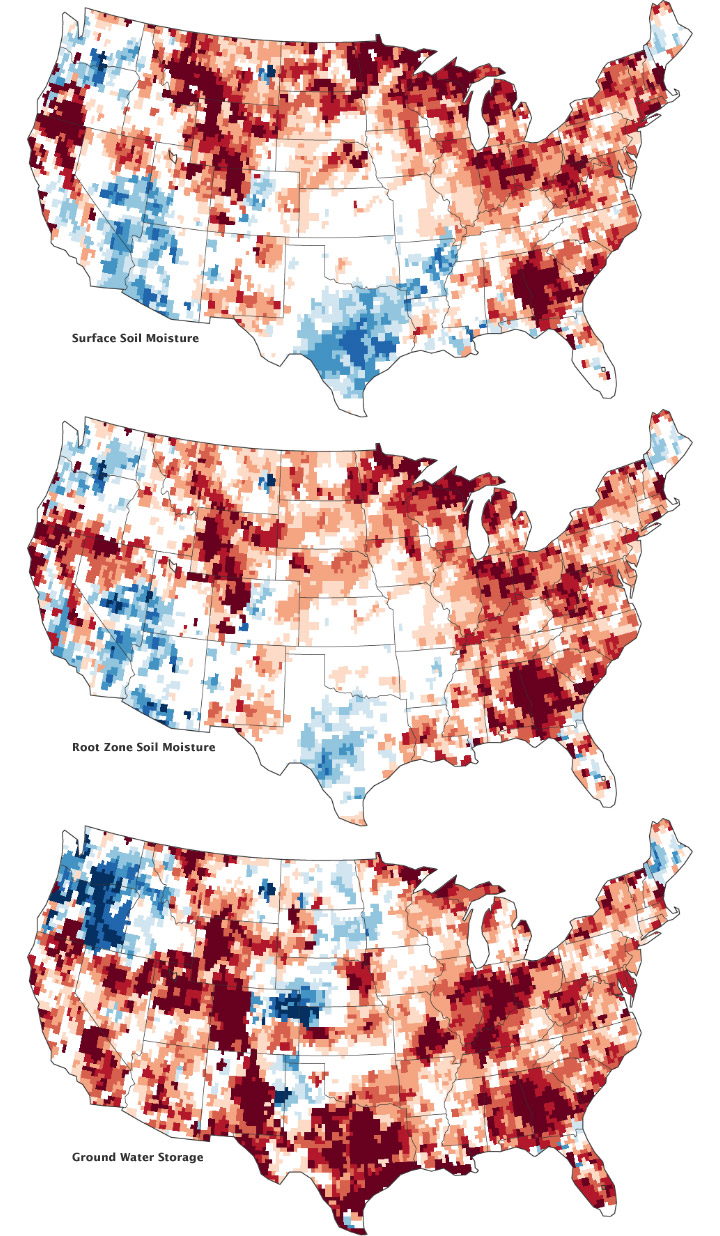

The maps above combine data from the twin satellites of the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) with other satellite and ground-based measurements to model the relative amount of water stored near the surface and underground as of September 17, 2012. The top map shows moisture content in the top 2 centimeters (0.8 inches) of surface soil; the middle map depicts moisture in the “root zone,” or the top meter (39 inches) of soil; and the third map shows groundwater in aquifers.

The wetness, or water content, of each layer is compared to the average for mid-September between 1948 and 2009. The darkest red regions represent dry conditions that should occur only 2 percent of the time (about once every 50 years). For a long-term view, download the animation below the third image, which shows the storage of groundwater from August 2002 through August 2012. (The animation is also available on YouTube.)

In all of the maps above, September 2012 conditions remain significantly drier than the norm, particularly in the eastern third of the United States, the Midwest, the High Plains and Rockies, and along the California–Oregon border. Surface and root moisture recently rebounded in the south central and southwestern states, largely due to Hurricane Isaac and other rainfall in 2012. But even there, the severe droughts of 2011 and 2012 persist below ground in aquifers. Groundwater supplies in the Southeast, the Rockies, the Midwest, New Mexico, and Texas are still far below the norm, according to GRACE.

All of the maps are experimental products funded by NASA’s Applied Sciences Program and developed by scientists at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and the National Drought Mitigation Center. The maps do not attempt to represent human consumption of water; but rather, they show changes in water storage related to weather, climate, and seasonal patterns.

“GRACE gives you variations in the total water stored on and in the land,” says NASA scientist Matt Rodell in a recent feature story on the Earth Observatory. GRACE does not measure the water directly, but instead detects changes in Earth’s gravity. When the satellites encounter a change in the distribution of Earth’s mass—such as a blanket of fresh snow on California’s Sierra Nevada—they are pulled toward the mountains a tiny bit more than normal. By tracking trends in how the satellite orbits change, researchers can calculate how gravity is changing on Earth. So when groundwater supplies dwindled in the United States in 2011 and 2012, that region of the planet had a little less mass and gravitational pull. The satellite orbits moved a bit in response, allowing GRACE to reveal the change in groundwater storage.

“To figure out whether those [gravity and mass] changes are happening in the ground water, soil moisture, snow, or surface water, we need auxiliary information,” Rodell adds. “We use physics equations and computer models to figure out what happens to the water after it hits the land as rain or snow.”

Read more about GRACE and studies of groundwater in the new Earth Observatory feature: The Gravity of Water.

Maps by Chris Poulsen, National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, based on data from Matt Rodell, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, and the GRACE science team. Caption by Mike Carlowicz, including reporting from Holli Riebeek.