It started out small, as such things usually do: someone planted a water hyacinth in a garden pond, attracted by the delicate lavender flowers and the thick mat of curling, lily-pad-shaped, waxy leaves floating on the surface of the water. But then the plant began to grow, doubling its area every 6 to 18 days, until the gardener pulled it from the pond and tossed it aside. That’s where the real problem began, because water hyacinth, known scientifically as Eichhornia crassipes, is among the world’s most noxious invasive weeds.

Native to the tropics of South America, the water hyacinth now thrives on every continent except Europe. It was introduced in Africa around 1879, and 110 years later, established itself on the continent’s largest lake, Lake Victoria. Spreading along the shorelines, the plant formed thick mats that covered an estimated 20,000 hectares (about 77 square miles) of the lake by 1998. Aggressive removal efforts, the release of the Neochitina weevil, which eats the plant, and environmental factors cut the plant back to manageable levels. But in December 2006, as the top satellite image reveals, the water hyacinth was back.

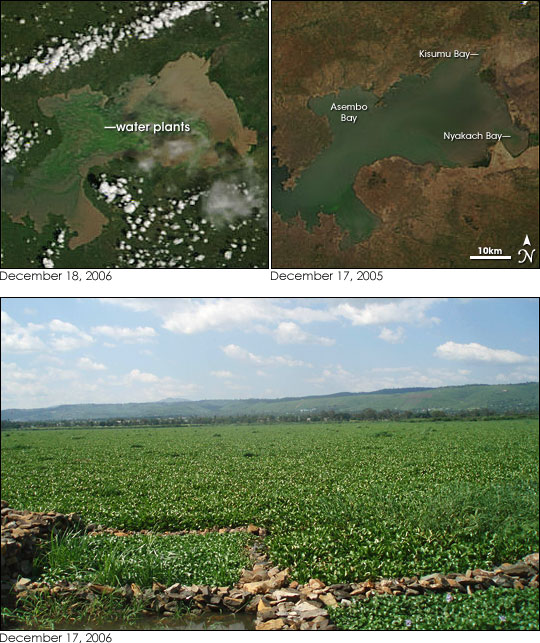

These images show the Winam Gulf, in the northeast corner of Lake Victoria in Kenya. The gulf was the most severely affected region during the first hyacinth outbreak in 1998, with as much as 17,231 hectares (67 square miles) of the plant growing on its surface. By 2000, the area covered by water hyacinth was down to about 500 hectares (2 square miles), and in December 2005, when the right image was taken, the lake appeared to be clear. In November and December 2006, however, unusually heavy rains flooded the rivers that feed into the Winam Gulf. The rain and floods raised water levels on the lake and swept agricultural run-off and nutrient-rich sediment into the water. As a result, the Winam Gulf was brown when the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite took the top left photo-like image on December 18, 2006. Vegetation around the lake was dramatically greener due to the rains.

The influx of fertilizer and sediments not only turned the water brown, but it also fed a fresh outbreak of water hyacinth. Bright green plants cover much of the Winam Gulf in the top left image. Though other plants such as algae may be contributing, water hyacinth is almost certainly one component of the soupy mass. As the photo shows, water hyacinth was growing along the shoreline, particularly in Kisumu Bay and Nyakach Bay. A comparison between December 2005 and December 2006 shows that Kisumu Bay was entirely covered by water hyacinth in 2006, and the shoreline of Nyakach Bay also appeared to change shape as the plant grew out from the shore.

The photo was taken on December 17, 2006, looking north across Kisumu Bay. The photographer stands on the shoreline and should be looking out over water, but only a field of green water hyacinth can be seen. The photo illustrates the problems the plant poses to the lake. The mat of vegetation is so thick that fishermen cannot launch their boats or bring fish to market on the shore. Sunlight does not filter through the plants, so native plants in the lake don’t get the light they need. The die-off of native plants affects fish and other aquatic animals. Water hyacinth clogs irrigation canals and pipes used to draw water from the lake for cities and villages on its shore. The plants impede water flow, creating abundant habitat for disease-carrying insects like mosquitoes. Water hyacinth can also sap oxygen from the water until it creates a ”dead zone” where plants and animals can no longer survive. Typically, only aggressive measures can control the fast-growing plant.

MODIS images courtesy the MODIS Rapid Response Team at NASA GSFC; photo and additional caption information courtesy Assaf Anyamba, Goddard Earth Sciences Technology Center (GEST/UMBC) and NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center, Biospheric Sciences.