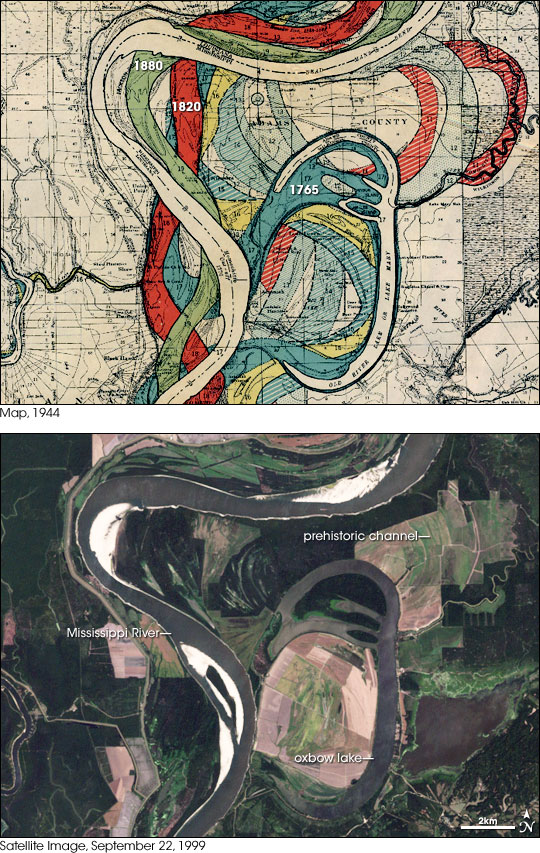

As it winds from Minnesota to the Gulf of Mexico, the Mississippi River is in constant flux. Fast water carries sediment while slow water deposits it. Soft riverbanks are continuously eroded. Floods occasionally spread across the wide, shallow valley that flanks the river, and new channels are left behind when the water recedes. This history of change is recorded in the Geological Investigation of the Alluvial Valley of the Lower Mississippi River, published by the Army Corps of Engineers in 1944.

This map of an area just north of the Atchafalaya River shows a slice of the complex history of the Mississippi. The modern river course is superimposed on channels from 1880 (green), 1820 (red), and 1765 (blue). Even earlier, prehistoric channels underlie the more recent patterns. An oxbow lake—a crescent of water left behind when a meander (bend in the river) closes itself off—remains from 1785. A satellite image from 1999 shows the current course of the river and the old oxbow lake. Despite modern human-made changes to the landscape, traces of the past remain, with roads and fields following the contours of past channels.

In the twentieth century, the rate of change on the Mississippi slowed. Levees now prevent the river from jumping its banks so often. The levees protect towns, farms, and roads near the banks of the river and maintain established shipping routes and ports in the Gulf of Mexico. The human engineering of the lower Mississippi has been so extensive that a natural migration of the Mississippi delta from its present location to the Atchafalaya River to the west was halted in the early 1960s by an Army Corps of Engineers project known as the Old River Control Structure (visible in the full-size Landsat image).

The delta switching has occurred every 1,000 years or so in the past. As sediment accumulates in the main channel, the elevation increases, and the channel becomes more shallow and meandering. Eventually the river finds a shorter, steeper descent to the Gulf. In the 1950s, engineers noticed that the river’s present channel was on the verge of shifting westward to the Atchafalaya River, which would have become the new route to the Gulf. Because of the industry and other development that depended on the present river course, the U.S. Congress authorized the construction of the Old River Control Structure to prevent the shift from happening.

Map courtesy the US Army Corps of Engineers, Landsat image by Robert Simmon, based on data from the UMD Global Land Cover Facility.