On September 19, Arctic sea ice reached its 2010 minimum, at 4.60 million square kilometers (1.78 million square miles). The National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) reported that 2010 Arctic sea ice extent was the third-lowest on the satellite record. (The record low, set in 2007, was 4.13 million square kilometers, or 1.59 million square miles.) The 2010 minimum was part of a larger pattern of overall Arctic sea ice decline dating back to at least the early 1970s.

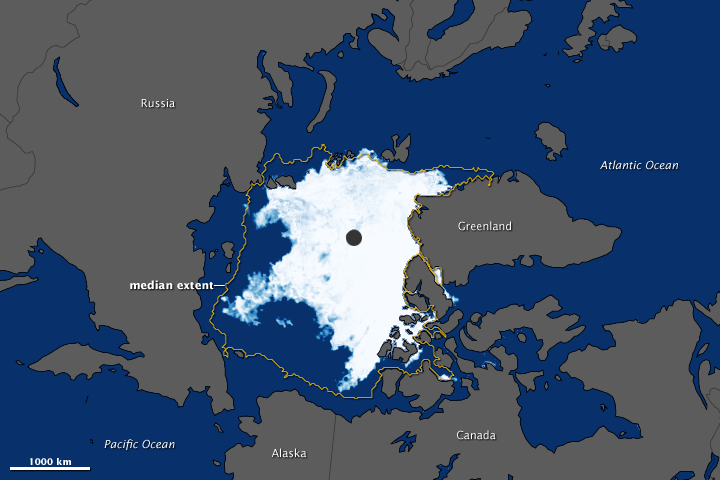

The top image, made from sea ice observations collected by the Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer (AMSR-E) Instrument on NASA’s Aqua satellite, shows sea ice extent on September 19, 2010. Ice-covered areas range in color from white (highest concentration) to light blue (lowest concentration). Ocean water is dark blue, and landmasses are dark gray. The yellow outline is the median minimum sea ice extent for 1979–2000; that is, areas that were at least 15 percent ice-covered in at least half the years between 1979 and 2000. Compared to the long-term average, sea ice concentration north of Alaska and eastern Siberia was especially low in 2010.

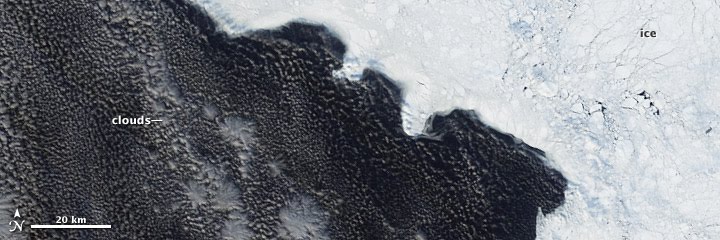

Arctic sea ice behavior was unusual in 2010 in that the sea ice appeared to reach its minimum extent on September 10 and began growing again. Acquired by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite, the middle and bottom images capture some of that ice growth, occurring in the East Siberian Sea. The middle image is from September 12, and the bottom image is from September 14. New, thin ice appears in the bottom image as rippled sheets, barely lighter than the underlying ocean water. This is probably nilas—thin sheets of ice with an oily or greasy appearance. (See the Earth Observatory Sea Ice feature article to learn more about different types of sea ice.)

After a few days of growth, sea ice declined again until September 19. According to NSIDC scientist Walt Meier, the renewed melting late in the season suggested that sea ice cover was thin and loosely packed. Those conditions make sea ice susceptible not only to melting, but also to disintegration by wind. In early September, NSIDC described large areas of rotten ice in an advanced state of disintegration.

The minimum sea ice extent in 2010 fits into a long-term pattern of decline, especially in multi-year ice, which persists through the summer melt season and into another winter. Multi-year ice may last for several years, eventually growing up to 4 meters (13 feet) thick.

First-year ice is thinner, saltier, and more vulnerable to melt. NSIDC stated that the 2010 season showed an increase in second- and third-year ice—which might eventually thicken—but the oldest and thickest ice had mostly disappeared from the Arctic.

“A band of thick ice is likely to persist along northern Greenland and northern Canada for some time,” said Ted Scambos, lead scientist at NSIDC. “But in the next 10 to 15 years, there could be substantial open water in the Arctic in the summertime.”

NASA Earth Observatory images created by Jesse Allen and Rob Simmon, using AMSR-E sea ice concentration data provided courtesy of the National Snow and Ice Data Center. Caption by Michon Scott.