Dust that blows off the Sahara Desert and over the Atlantic Ocean can neutralize acid rain, reduce sea surface temperatures by reflecting incoming sunlight, carry fungal and bacterial diseases to distant continents, foul Caribbean coral reefs, and stimulate the growth of ocean phytoplankton by delivering iron, which is often lacking in ocean waters far from land.

Satellites are among the most important tools Earth scientists have for monitoring the number, intensity, and spread of desert dust around the globe. This panel of images shows how scientists use observations from two different sensors on NASA’s Terra satellite to track dust storms off West Africa.

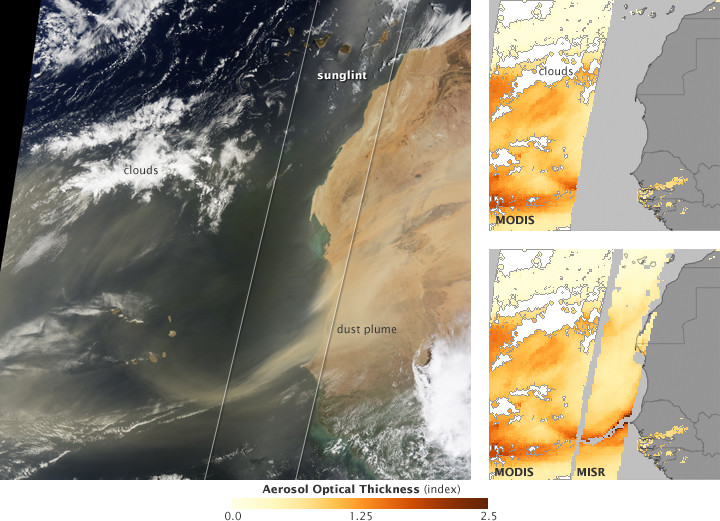

A photo-like image from Terra’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on July 12, 2009 (left), shows a dust storm in progress and reveals where dust plumes are thick or thin. But scientists who want to know, for example, whether dust storms will affect sea surface temperatures during hurricane season need more than pictures; they need numbers—dust concentrations at different locations and altitudes, and particle sizes—that can be fed into weather and climate models.

To translate pictures into numbers, scientists create a scale (index) of how transparent the air was when the satellite observed it. To make this index, called aerosol optical thickness, scientists must know things like the intensity of incoming sunlight, how a “clean” atmosphere would scatter or absorb light, and how much light the satellite sees reflected from the surface.

Over the ocean, there is a portion of all MODIS images where sunglint—the mirror-like reflection of the Sun off the water—makes it impossible for scientists to calculate how transparent the air is. It occurs in the spot where the angle of incident sunlight is roughly the same as MODIS’ angle of view. The sunglint area has to be left empty (missing data, gray) in MODIS aerosol optical thickness images (top right).

A second sensor on Terra, the Multi-angle Imaging Spectroradiometer (MISR), doesn’t see as wide an area as MODIS, but it has multiple cameras that view the surface at different angles. Multiple viewing angles mean that MISR always has several views of the surface that aren’t affected by sunglint, and scientists can calculate aerosol optical thickness across the entire field of view (except where there are clouds or where the dust is so thick that the surface is completely blocked from view).

By combining measurements from both sensors (bottom right image), NASA scientists get a more complete picture of the concentration and transport of Saharan dust. These results can improve how dust aerosols are represented in climate, weather forecast, and transport models. Similar measurements from Terra of aerosol particles like smoke and urban pollution have been incorporated into U.S. regional air quality forecasts.

NASA image created by Jesse Allen, using MISR data obtained from the Langley Atmospheric Science Data Center and MODIS data from the Goddard Level 1 and Atmospheric Archive and Distribution System (LAADS). Caption by Rebecca Lindsey.