In late August 2023, Hurricane Idalia barreled toward the Big Bend region of Florida, intensifying from a Category 1 to a Category 4 storm in less than 24 hours over warm Gulf waters. The hurricane made landfall as a still-powerful Category 3 storm on the morning of August 30, 2023, with maximum sustained winds nearing 125 miles (205 kilometers) per hour.

A hurricane meets the threshold for rapid intensification if its wind speeds increase at least 35 miles (55 kilometers) per hour in 24 hours. Idalia cleared that bar and then some. Conditions such as high sea surface temperatures, excess ocean heat content (a measure of the water temperature below the surface), and low vertical wind shear can fuel rapid intensification.

But the typical ingredients for intensification do not fully explain Idalia’s extraordinary growth, according to the authors of a recent analysis of the hurricane. For example, while sea surface temperatures were sufficiently high along its track, the storm encountered a more favorable wind environment earlier in its journey, when it did not rapidly intensify, than when it ultimately did.

An additional factor, the study’s authors posited, may have been the presence of a large freshwater plume that helped sustain warm sea surface temperatures along the continental shelf as the storm passed over. River discharge along the Gulf Coast created a distinct layer of less dense, low-salinity water that resisted mixing with the rest of the water column, they found.

“Wind wants to mix the water, bringing cold water up to the surface and warm water down to the depths,” said marine scientist Chuanmin Hu, one of the study’s authors. “But the density gradient between surface fresh water and deeper salty water makes this difficult.” Consequently, the hurricane could keep absorbing energy from the warm sea surface as it churned overhead, he said.

River plumes have been studied more extensively in the context of tropical cyclone development in other areas, namely the Amazon and Orinoco plumes off South America. One study of hurricanes found that more than two-thirds of storms between 1960 and 2000 that reached Category 5 strength passed over the historical region of those plumes.

Similar expanses of fresh water develop off the U.S. Gulf Coast—another area where destructive storms can form—almost every year with varying magnitudes, Hu said. Funded in part by NASA, he and colleagues from the University of South Florida and the University of Miami initially set out in August 2023 to study phytoplankton and dissolved matter in the river plume using satellite and ocean glider data. As it turned out, mapping the approximately 20-meter (65-foot) thick layer—a barrier capable of isolating cold water beneath it—was a boon in understanding the major storm that would sweep through.

They found that the plume in 2023 was particularly expansive, persistent, and low-salinity. The map at the top of this page uses observations from the SMAP (Soil Moisture Active Passive) satellite. It reveals a large area of low sea surface salinity off the U.S. Gulf Coast shortly before Idalia passed over it. Ocean salinity is measured in practical salinity units (PSUs), equaling the number of grams of salt per 1,000 grams of water.

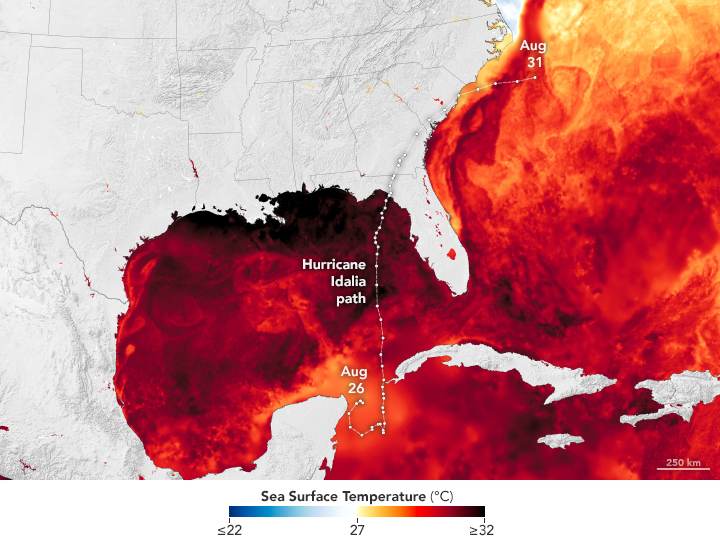

In addition to the stratified water, high sea surface temperatures were a contributing factor in Idalia’s intensification, Hu said. 2023 was a warm year for Florida waters and for oceans globally. The map above shows sea surface temperatures on August 27 based on data from the Multiscale Ultrahigh Resolution Sea Surface Temperature (MUR SST) project, a NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory effort that blends measurements of sea surface temperatures from multiple NASA, NOAA, and international satellites, as well as ship and buoy observations.

“The whole Gulf was warmer than usual, even without the salinity [effect],” Hu said. That the storm occurred in August—not later in the hurricane season when the water might have been cooler overall—meant there was more heat available to fuel the storm.

Still, without the barrier of the low-salinity layer, Hu said, “it’s difficult to explain why Idalia intensified so quickly.” He and his coauthors argue that incorporating river plumes in forecast models may improve the accuracy of intensity predictions. “If you have a persistent river plume in the right location at the right time,” Hu said, “you may have a perfect storm.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using sea surface salinity data courtesy of JPL and the SMAP Science Team and the Multiscale Ultrahigh Resolution (MUR) project. Story by Lindsey Doermann.