For much of September and October 2023, satellites detected widespread fire activity in Bolivia’s lowlands. That’s common in a country with a long-standing practice of lighting fires to stimulate new growth in pastures and to clear land for crops. But the fires this year were especially fierce at times due to ongoing drought and heat.

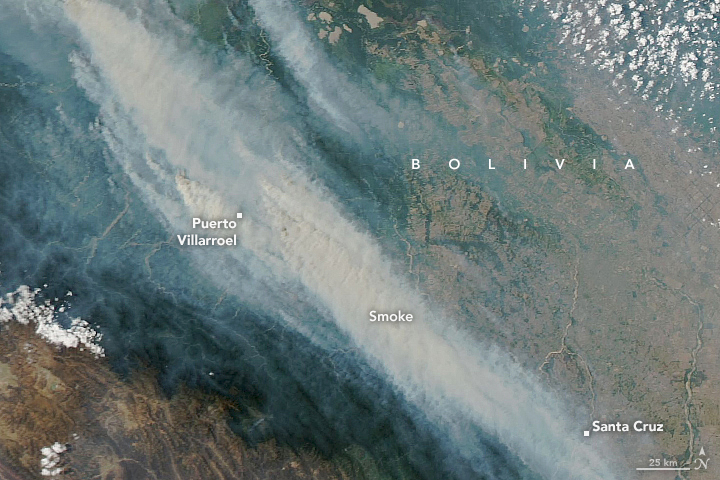

On October 22, 2023, VIIRS (the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite) on the NASA-NOAA Suomi NPP satellite acquired this image of smoke streaming from fires burning in parts of the Bolivian departments of Beni, Santa Cruz, La Paz, and Cochabamba. A detailed view (below) from MODIS (the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) on NASA’s Aqua satellite shows intense fires burning along the Ichilo River east of Puerto Villarroel, an area that has experienced widespread deforestation to its east in recent decades.

Fires occur in this region every year and are usually the result of human activity, explained Oswaldo Maillard, a researcher with the Bolivian-based nonprofit, the Foundation for the Conservation of the Chiquitano Forest. One of the most common causes is a slash-and-burn practice called chaqueo, the seasonal burning of pastures and crops to clear away old vegetation and prepare the soil for planting. Fires are also used to burn off piles of trees that have been cut to make space for new fields and pastures.

However, the unusual heat and severe drought that have parched Bolivia in recent months and years energized and intensified these seasonal chaqueo fires. Some of them spread into natural ecosystems, including the grasslands of the Beni savanna and the Chiquitano forests of northern and eastern Bolivia. During the peak of the burning in late October, the smoke was so heavy that the Bolivian government closed some 3,650 schools—about 15 percent of the national total, according to news reports.

“Fires are recorded every year,” Maillard said. “But they became a major story on Bolivian television and in newspapers in October because smoke was carried in a southeasterly direction into Santa Cruz, Bolivia’s largest city.”

The SERVIR Amazon Fire Dashboard, a project of NASA and USAID, registered 7,761 active fires in Bolivia on October 22, 2023. Nearly half of these (3,148) were classified as savanna or grassland fires, with many of them burning in the Beni Savanna. Many others (3,380) were classified as small-scale land clearing and agriculture fires, which were more evenly distributed throughout all parts of the country.

The rest of the fires detected that day by VIIRS were either deforestation fires (741) or understory fires (492). Though smaller in number, these two types of fires are especially significant because they cause long-term damage to forests, explained Douglas Morton, an Earth systems scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. While grasslands can grow back the next year after a fire, it typically takes burned tropical forests many decades or longer to recover. Most of these fires, including those shown near Puerto Villarroel, occurred in corridors of development along rivers and roads.

Deforestation is on the rise in Bolivia. According to the World Resources Institute’s Global Forest Watch, Bolivia saw a record-high level of primary forest loss in 2022, an increase of 32 percent from 2021 levels. For the third year in a row, Bolivia was third behind only Brazil and the Democratic Republic of the Congo in primary forest loss, the institute reported.

Bolivia’s Ministry of Defense reported that nearly 3,825 firefighters and 45 military units played a role in fighting wildfires between June and November 2023. According to the Bolivian government, more than 2.7 million hectares (10,000 square miles), an area roughly the size of Vermont, had burned as of November 2023. That’s down somewhat from 2019, 2020, 2021, and 2022—all years when more than 4 million hectares burned.

After the widespread fire activity in September and much of October, a period of rain during the last week of October helped tamp down many of the fires. “However, most of the large fires are still burning as of November 6,” said Morton. “It often takes a sustained period of rain to truly extinguish a fire and prevent spread in grassland and forest areas.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using VIIRS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE, GIBS/Worldview, and the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership and MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview. Story by Adam Voiland.