In early September 2022, floods in Pakistan were the worst in a decade. Monsoon rains had pummeled the region for several weeks and floodwaters inundated 75,000 square kilometers of the country. Six weeks later, rains have ceased, and fields have begun to drain. But vast swaths of farmland remain waterlogged, infectious diseases are spreading, and food shortages loom.

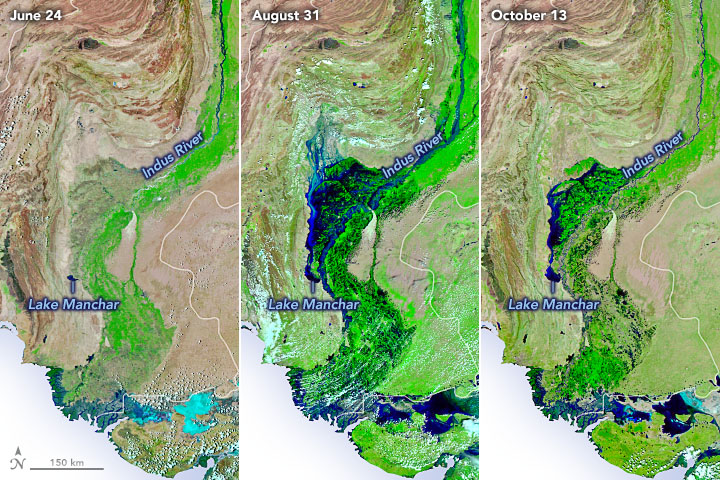

The images above show the progression of the flooding. The second image shows Sindh province on August 31, 2022, near the peak of the flooding. By October 13, 2022 (third image), a considerable amount of water had drained off the landscape and back into rivers. But many areas remained wet and waterlogged in comparison to June 2022 (first image). All three images were acquired by the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the NOAA-20 satellite. They are false-color images based on VIIRS observations of shortwave infrared and visible light, a combination that makes it easier to distinguish between water (blue) and land (green).

Rains in September 2022 were modest. Rather, the flooding visible in these images was caused by the arrival of torrential monsoon rains that hit southern Pakistan in July and August. (The rains were likely made more intense by climate change, according to the World Weather Attribution Initiative.)

The animation above depicts a satellite-based estimate of rainfall from July 1 to August 31, 2022. The darkest reds reflect the highest amounts of rainfall, with Pakistan’s Sindh and Balochistan provinces seeing the heaviest rains. The data are remotely sensed estimates that come from the Integrated Multi-Satellite Retrievals for GPM (IMERG), a product of the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) satellite mission. Due to the averaging of the satellite data, local rainfall amounts may be significantly higher when measured from the ground. Sindh and Balochistan received four times more rain than usual for this period, according to data from the Pakistan Meteorological Department.

With so much standing water in fields for so many weeks, the floods have taken a toll on Pakistan’s farmers. One satellite-based assessment conducted by researchers at the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) forecasted that floodwaters would likely reduce Sindh's cotton crop by 88 percent, rice crop by 80 percent, and sugarcane crop by 61 percent.

“Unlike previous floods, the current floods have inundated areas where there is little possibility that water can drain naturally,” explained Faisal Mueen Qamer, a remote sensing specialist with ICIMOD. “Local governments are currently making cuts to roads and other linear infrastructure to make it easier for the water to flow back to rivers or toward empty lands. Some farmers are operating pumps to help drain their lands before planting winter crops.”

Yet with many fields still waterlogged in October, some farmers may have to delay or abandon planting winter crops, such as wheat. The deaths of more than 1.1 million livestock animals during the flooding has further strained the food system in Pakistan. With food prices soaring, World Food Organization and U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization assessments reported that the number of people requiring emergency food assistance will increase from 7.2 million prior to the flood to 14.6 million from December through March 2023.

Flood-hit communities have also seen outbreaks of waterborne diseases, with news outlets reporting outbreaks of dengue, cholera, and malaria.

NASA Earth Observatory images and video by Joshua Stevens, using VIIRS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE, GIBS/Worldview, and the Joint Polar Satellite System (JPSS) and IMERG data from the Global Precipitation Mission (GPM) at NASA/GSFC. Story by Adam Voiland.