As extreme summer heatwaves deepened droughts and fueled wildfires in the Northern Hemisphere, winter storms brewed south of the equator. In July 2022, back-to-back weather systems eased rainfall deficits in central Chile and added to the snowpack atop the Andes—a critical reserve of water for the coming summer.

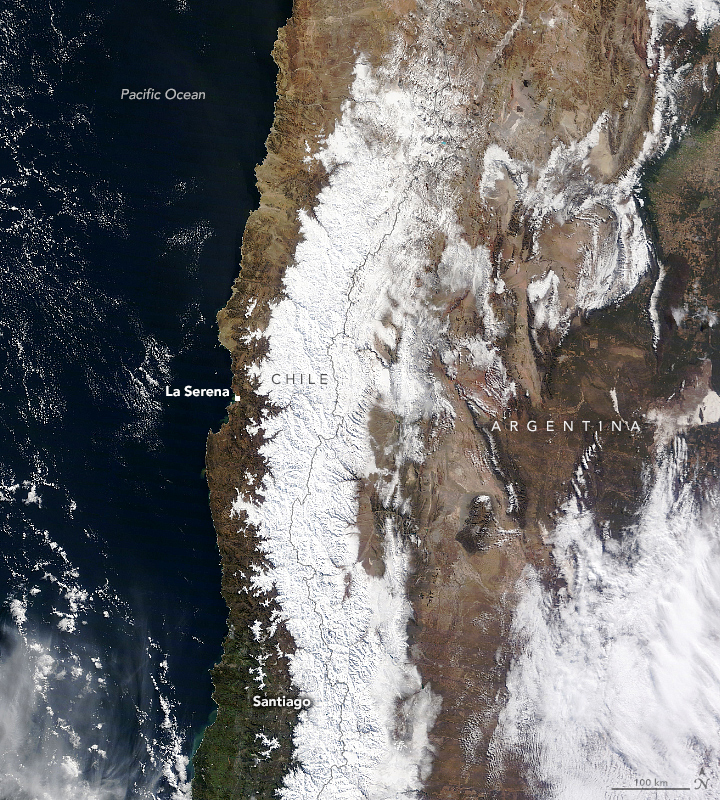

The blanket of fresh snow along the mountain range between Chile and Argentina is visible in the image above, acquired on July 16 by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite. Heavy rain and snow fell in the area despite La Niña conditions offshore in the Pacific that typically bring dry winters. The precipitation brought at least some temporary relief to an area suffering a decade-long drought.

The storms were the result of a blocking anticyclone atmospheric pattern near the Antarctic Peninsula that steered several extratropical cyclones toward Chile. Two weather systems—on July 9–10 and July 14–15—dumped rain along the coast and snow in mountains. According to news reports, the storms left hundreds of people stranded in a mountain pass, where more than 1 meter (3 feet) of snow accumulated on the roads.

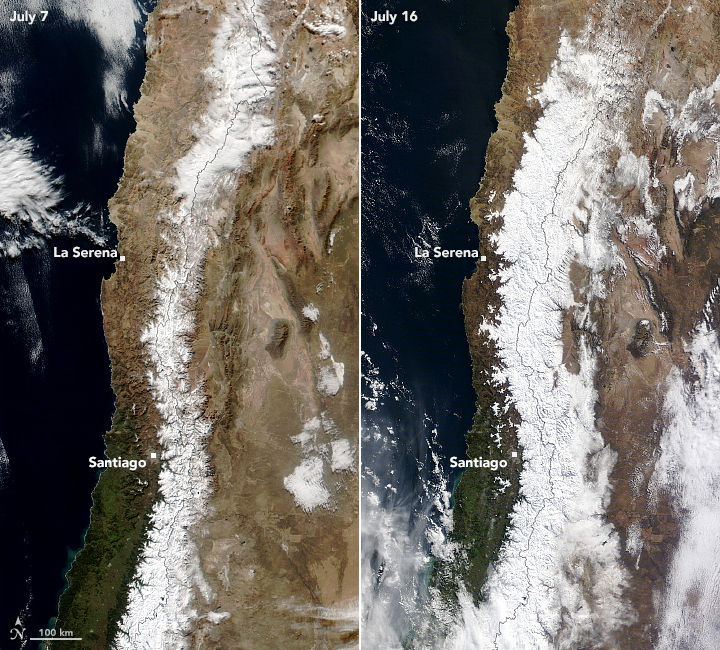

“Until 10 days ago, north-central Chile was experiencing one of its driest winters,” said René Garreaud, a scientist at the University of Chile. The change from dry to wet was swift and visibly striking. The Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the NOAA-20 satellite acquired a view of the same area on July 7 (left), just prior to the storms. Notice the relatively sparse snow cover compared with the July 16 image (right) acquired after the storms.

On July 7, the coastal city of La Serena had a year-to-date rainfall deficit of about 80 percent (compared to the mean from 1990-2020). The storms delivered 8 centimeters (3 inches) of rain, bringing the city to a 64 percent surplus. Farther inland, Santiago’s rainfall deficit improved from 70 percent to 27 percent. “These rapid changes are not unusual in arid regions, where the bulk of the annual accumulation is accounted for by a handful of frontal systems,” Garreaud said.

As water deficits eased in places, Garreaud said he hopes it will reduce the odds of a water shortage next summer. That depends in part on the state of the mountain snowpack, which is a particularly important water source for drinking, power generation, and agriculture. “This is our savings account for next summer,” he said.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview and VIIRS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE, GIBS/Worldview, and the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership. Story by Kathryn Hansen.