Spring is a time of major transformation across interior Alaska, as snow melts off the land and ice breaks up along the rivers. The transition is especially apparent within the Innoko Lowlands, a group of vast, flat floodplains traversed by the Yukon and Innoko rivers. Seasonal melting here can lead to flooding so widespread that it is visible from space.

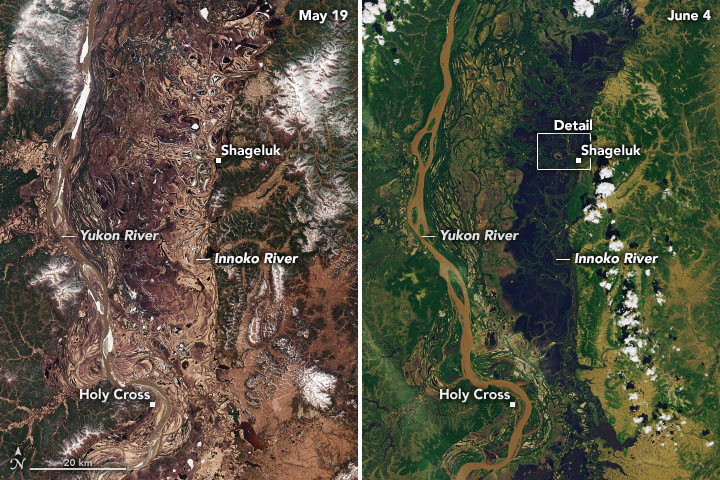

The transition is evident in these natural-color images, acquired by the Operational Land Imager-2 (OLI-2) on Landsat 9. The left image shows the lowlands on May 19, 2022, during a typical mid-spring day. The right image shows the same area on June 4, 2022, after meltwater had inundated the landscape.

The Innoko River is a major tributary of the Yukon River. It originates in the Kuskokwim Mountains and flows north and then southwest for about 500 miles (800 kilometers) before joining the Yukon near the town of Holy Cross. Lakes, wetlands, and forests dot the landscape, and a complex network of sloughs meander between the two rivers. In mid-spring there are still patches of snow on the land and ice on the Yukon. By late-spring, the landscape has greened up and water (dark brown) has spilled far beyond the banks of the Innoko.

Some of the flooding was likely caused by chunks of river ice that blocked the flow of water—a phenomenon known as an ice jam that can cause rivers and their tributaries to rise and spill over their banks. On May 21, 2022, the National Weather Service issued a flood watch due to an ice jam for parts of the Yukon and for the Innoko River from Shageluk to 20 miles (32 kilometers) upstream. But according to Christopher Arp, a scientist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, the melting of deep snowpack from this winter likely contributed, too.

The small Native village of Shageluk, about 330 miles (530 kilometers) west of Anchorage, stands out amidst the flooding. According to Joyanne Hamilton, a resident of Shageluk and a citizen scientist, high water and the occasional extreme flooding around Shageluk is a typical springtime occurrence. “It is in our oral histories that we know of these things,” Hamilton said. “It was normal to have extreme flooding years.”

Hamilton noted that 2022 seems to be one of the more extreme years. “The last time in my experience where it flooded this much was in 1992, when literally the water current changed directions,” she said. The floods that year inundated the airport. Flooding this year did not reach the airport, but access roads were submerged, requiring people to reach the airport by boat.

Some of the flooding and its disruptions were documented in pictures and video from citizen scientists as part of Fresh Eyes on Ice. The project, co-funded by NASA, aims to increase observations of ice conditions on Alaskan lakes and rivers.

The Innoko River’s consistently high springtime water levels led the people of two major villages to relocate in the 1960s. The village of Holikachuk relocated to Grayling on the Yukon, and Shageluk now sits on higher ground about 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) south of its original location. Shageluk is the last inhabited village along the Innoko River.

Hamilton explained that there were many more villages along the Innoko River in the past. High water and subsistence activities caused people to move, but they would return depending on the season. “Places on the Innoko are still not considered abandoned and are owned by our people as tribal lands and Native allotments under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA),” Hamilton said. “The Innoko area was well-settled for centuries, even with the yearly spring flooding.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Kathryn Hansen with input from the Adolph Hamilton family stories and experiences.