The waters off the Pacific coast of northern Peru routinely build what has been called the world’s longest wave. There’s no way to know for sure, but the seemingly endless waves that roll up to the fishing town of Puerto Malabrigo (Chicama) are legendary among surfers. While some famous wave breaks around the world can be ridden for seconds, the breaks at Chicama can be ridden for minutes.

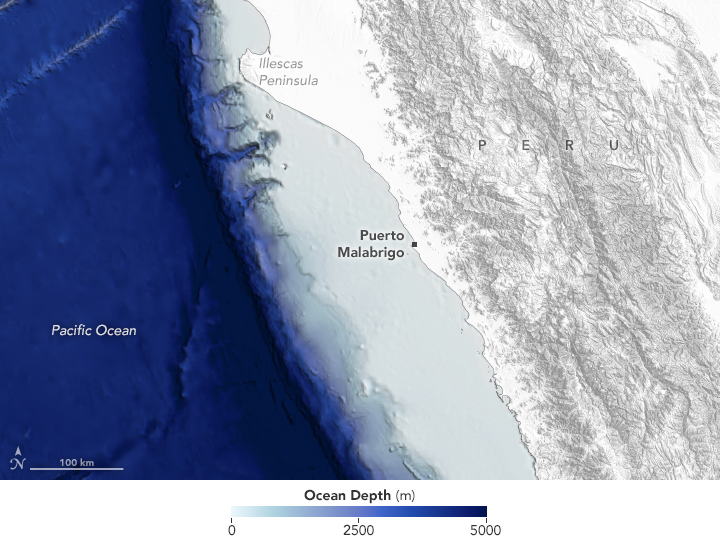

The swells responsible for Chicama’s famous waves are visible in this image, acquired on March 23, 2021, with the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8. Notice the row after row of the waves neatly lining up as they approach the coast.

According to Andrew Thomas, an oceanographer at University of Maine and ex-surfer, the swell is generated by storm systems and weather fronts hundreds to thousands of miles away in the Pacific Ocean—and occasionally the Southern Ocean. As the waves propagate across the open water, waves of similar wavelengths (and speed) become sorted and start to travel together. “Because the coast of Peru is very deep,” Thomas said, “these large swells will continue their journey until very close to shore.”

Another fortuitous feature for surfers is that the waves arriving from the open ocean roll nearly parallel to this part of Peru’s coastline. “This is not common in Peru or Chile, where the waves mostly just crash into a coast that is perpendicular to the direction of swell propagation,” Thomas said. The arrangement means Chicama’s waves can progressively break along a long stretch of shoreline.

The breaks that surfers most frequently ride begin along the cape that juts out into the Pacific. This is where four points—Malpaso, Keys, El Point, and El Hombre—trigger the crest of a swell to overturn and peel as it approaches the shallowing shore. Chicama’s waves break left, which means they peel from left to right from the perspective of an observer on the shore. Large swell is most consistent from March through November, during which time some of the sections occasionally connect. The distance from Malpaso to the pier is nearly 4 kilometers (2.5 miles), but surfers usually have to catch multiple waves to make it the entire distance.

The coastal and oceanic conditions set up what Thomas called a “dreamland for surfers.” So much so that in 2013 the area gained protection from the Peruvian government against development and infrastructure that would harm the waves. Since Chicama, the first wave to be listed in the Protected Waves Registry, dozens more waves across Peru have been added to the list.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey, bathymetry data from the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO) and topographic data from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM). Story by Kathryn Hansen.