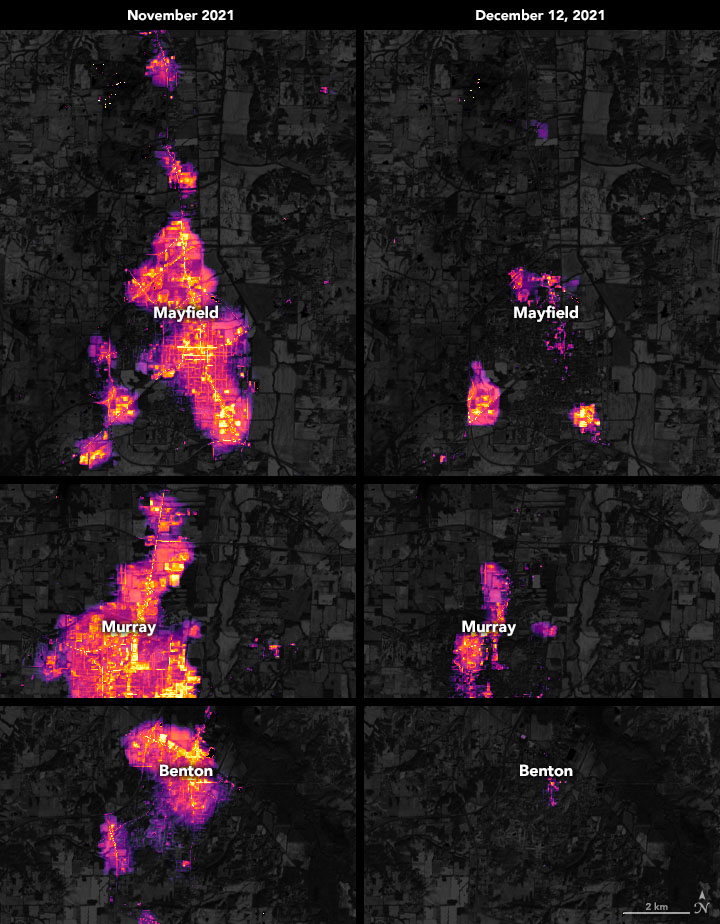

On the night of December 10-11, 2021, a potent storm front and dozens of tornadoes blew across the midwestern United States, killing more than a hundred people and destroying homes and businesses across at least four states. One of the worst-hit areas was western Kentucky near the town of Mayfield. As of December 15, nearly half of the customers in Graves County were still without power.

The maps above show nighttime light emissions before and after the severe storms passed through Kentucky. A team of scientists from the Universities Space Research Association (USRA) and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) processed and analyzed data from the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the NOAA–NASA Suomi NPP satellite. The base map was built from data collected by the Landsat 8 satellite. The November image is a composite of lighting across the month, representing the baseline, pre-storm conditions.

VIIRS measures nighttime light emissions and reflections via its day/night band. This sensing capability makes it possible to distinguish the intensity of lights and to observe how they change. (Sometimes this can help decipher sources and types of light.) The data are processed by researchers in the USRA-GSFC Black Marble Project to account for changes in the landscape, the atmosphere, and the Moon phase, and to filter out stray light from sources that are not electric lights.

“Because VIIRS DNB satellite data is global in scope, it is especially useful for assessment of the impacts of large-scale disasters like this tornado,” said Kellie Stokes, a USRA scientist in The Black Marble Project. “Though these images show only towns in Kentucky, outages were perceived by Black Marble across a large swath in the Midwest and as far north as the Great Lakes. The Black Marble product is available in near-real time—within about 3 to 5 hours—making it often one of the first datasets available for disaster assessments, particularly in remote areas.”

Precision is critical for studies with night lights. Raw, unprocessed images can be misleading because moonlight, clouds, pollution, seasonal vegetation—even the position of the satellite—can change how light is reflected and can distort observations of human-made lights.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using Black Marble data courtesy of Ranjay Shrestha/NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Text by Michael Carlowicz.