Each January, the Himalayas are typically blanketed with fresh snow. But unusual winter melting in recent months has left several glaciers and mountains without a new coating. Many glaciers are bare even at their crest.

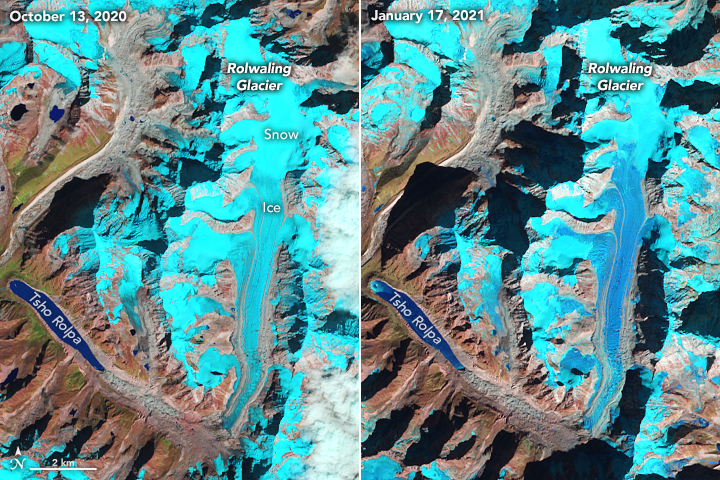

The false-color images on this page show a few glaciers in the Himalayas. The images above show the high glacier passes of Nanpa La and Nup La, located around 30 miles (50 kilometers) northwest of Mount Everest, during fall on October 13, 2020 (left) and in winter on January 17, 2021 (right). The images below show Rolwaling Glacier, located 20 kilometers (30 miles) south of Nanpa La. All images were acquired by the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 using bands 7-5-4.

In these images, short wavelength infrared (SWIR) bands are combined with natural color to better differentiate areas of water that are snow (brightest blue), ice (darker blue) and meltwater (darkest blue). Rocks are brown; vegetation is green. Note black areas are shadows.

From October 2020 to January 2021, the average snow line—the boundary where snow-covered surfaces meet bare ground—on these glaciers rose around 100 meters (330 feet), indicating significant melt.

“A substantial area of the glaciers are now probably experiencing melting year round,” said Mauri Pelto, a glaciologist at Nichols College. “In years past, most melting stopped during winter and the snow line didn’t move, but that’s not really the case now.”

Melting season in the region around Mount Everest is usually concentrated during the summer monsoon (April to September). In the past year, however, abnormally warm temperatures have extended the melting period by four months. As of January 22, 2021, weather stations at Everest base camp reported maximum temperatures above freezing for eight days that month. On January 13, temperatures peaked at 7°C (45°F).

“We have been basically seeing spring and summer-like conditions in the middle of winter,” said Tom Matthews, a climate scientist at Loughborough University (United Kingdom) who helps manage weather stations at Mount Everest placed during the Rolex National Geographic Expedition. These melting events, said Matthews, are associated with pulses of warm air carried in by prevailing winds from the west.

Matthews and colleagues also observed less snow accumulating during the summer monsoon in recent years. Generally, the summer monsoon delivers about 75 percent of the region’s annual snow accumulation. The team, however, noted an increase of rain and melting during the summer monsoon in 2019 and 2020 that reduced the amount of lasting snowfall near Everest.

Due to less-than-normal seasonal snowfall, the warm temperatures are melting snow that was accumulated before the monsoon season. “I have seen snow-free situations last into January before, but usually the snow line isn’t this high to start with,” said Pelto.

Colder weather and new snowfall is needed to pause the melting, said Pelto. Since January 23, temperatures have dipped below freezing, but snowfall is still light and conditions are dry. Dry, colder weather drives sublimation, converting the solid snow directly to a gaseous state into the air and further reducing the snow cover.

“I don’t think the ablation (melting) season is near ending. Until you get new snowfall, you will continue to experience melting and sublimation.” said Pelto. “It is evident that the ablation season length and ablation area on these high elevation glaciers is expanding.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Kasha Patel.