With its population rising three times faster than the national average, the Charleston metropolitan area is among the fastest growing places in the United States.

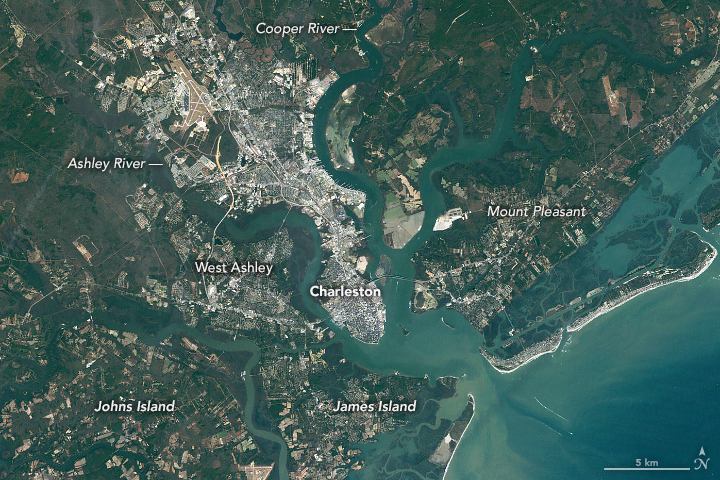

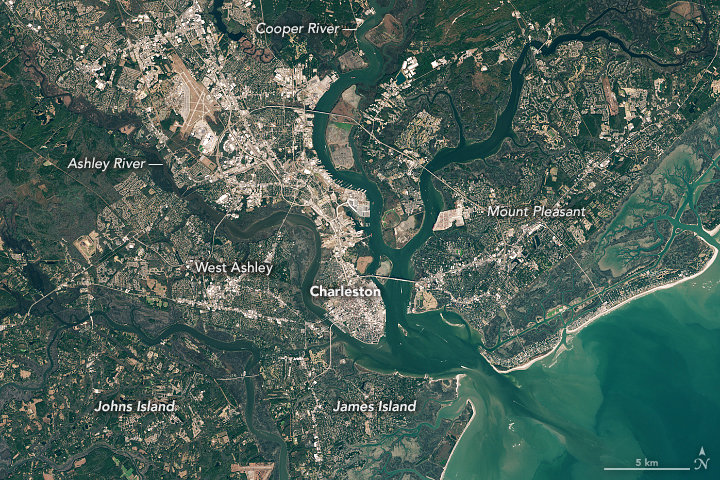

Large tracts of coastal forests and farmland have been cleared and developed in recent decades to accommodate new residents to the area. The pair of natural-color Landsat images above—the first image from 1985 and the second from 2020—show some of the changes. Forests and marshes appear green; developed areas are gray. Places where widespread development has occurred include James Island, Johns Island, Daniel Island, West Ashley, and Mount Pleasant.

A similar story is playing out in cities all across the United States, but the Charleston area stands out in one critical way—much of the new development has happened on low-lying land that is especially vulnerable to sea level rise and flooding. Older, more established parts of Charleston—often on slightly higher land but surrounded by water on three sides—faces similar challenges. As one form of remediation, local and federal government officials are moving forward with plans to build a seawall to protect the city’s historic downtown from encroaching water.

“Other southeastern coastal cities face similar problems but with one caveat: the lowcountry of South Carolina is low,” said Norman Levine, director of the Santee Cooper GIS Laboratory and Lowcountry Hazards Center at the College of Charleston. “Over one-third of all homes are built on land that sits below 10 feet (3 meters) of elevation.”

However, hurricane storm surges up to 9 feet have been measured in the past, and climatologists expect surges to grow larger as global climate warms and storms become more intense.

High tide, or “nuisance flooding,” is already far more common now than it was decades ago, according to Dale Morris, the coauthor of a 2019 report that assessed the region’s flood risks. On average, Charleston saw 10 to 25 tidal floods per year in the 1990s. There were 89 such events in 2019 and 69 in 2020, he said. In other words, the city now sees tidal flooding every 4 to 5 days.

Both problems are amplified by sea level rise. Relative sea level in Charleston has risen by 10 inches (25 centimeters) since 1950, with an acceleration to 1 inch (3 centimeters) every 2 years since 2010.

“If you look at a lot of the recent development, it impinges upon or is in low-lying floodplains and adjacent land,” said Morris. “These areas used to flood and no one really noticed. Now they flood and impact people’s lives, resources, and livelihoods.”

The report offers some general principals and recommendations for future development. Development should respect the landscape's natural drainage patterns and soil qualities. Coastal forests—which sponge up water—should be preserved wherever possible. And according to the report authors, development on the lowest-lying areas should not happen.

“We are not saying don’t develop at all,” said Morris. “We are saying to develop wisely, carefully, sensibly given the current and future flood risks. Those risks are not going to decrease.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Adam Voiland.