Like Earth, the dwarf planet of Pluto has mountains. Like their earthly cousins, some of those peaks are covered in blankets of white. But the origins of these ice-like deposits are very different.

According to new research published on October 13, 2020, in Nature Communications, some of the mountains discovered on Pluto during the flyby of the New Horizons spacecraft in 2015 are covered by a blanket of methane ice. An international team of scientists analyzed data from Pluto’s atmosphere and surface and used numerical simulations of its climate to reveal that these ice caps are created through different processes than they are on Earth.

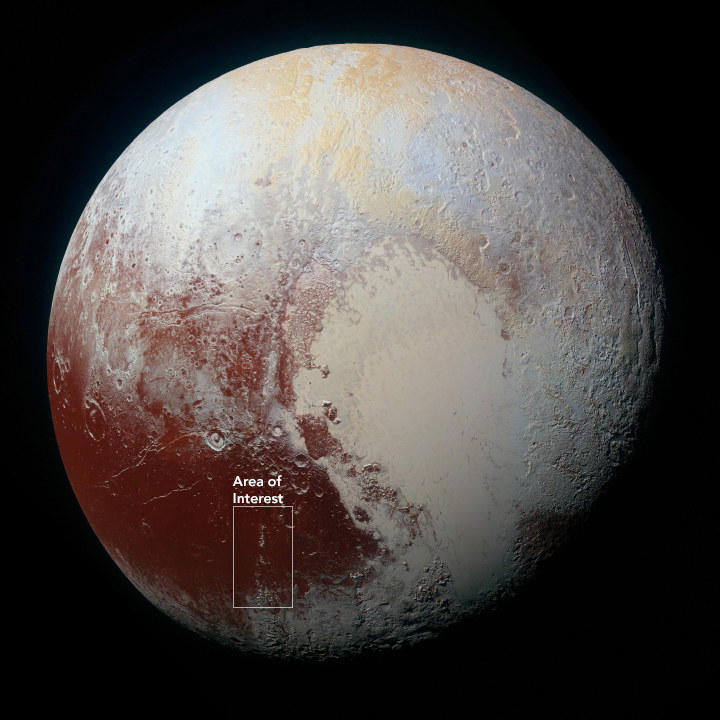

The study authors noted that “within the dark equatorial region of Cthulhu, bright frost containing methane is observed coating crater rims and walls as well as mountain tops, providing spectacular resemblance to terrestrial snow-capped mountain chains.”

The image at the top left was acquired on July 14, 2015, when the New Horizons spacecraft approached Pluto. The Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) detected the presence of patchy bright deposits atop the Pigafetta Montes and Elcano Montes mountain ranges. The spacecraft’s Multispectral Visible Imaging Camera (data not shown) revealed signatures of methane.

The top right image is a natural-color view of a section of the Alps range in Europe and was acquired by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite on March 19, 2020.

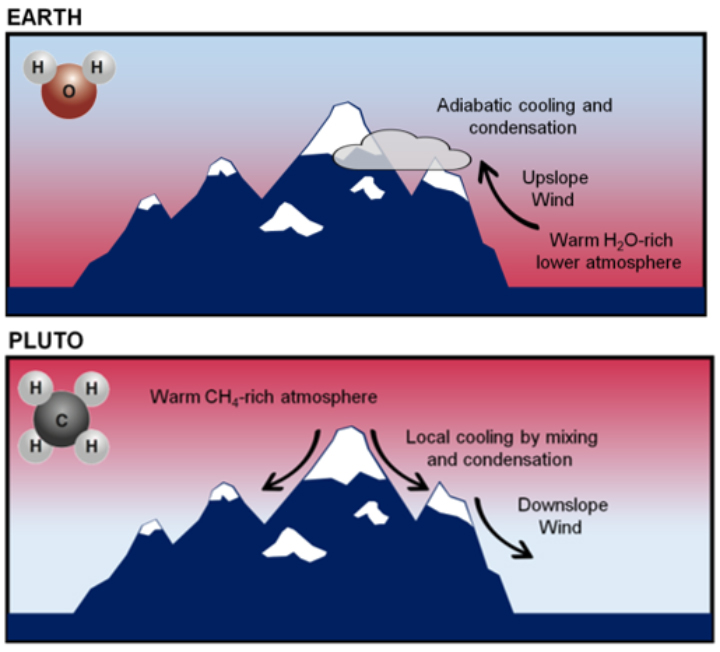

On Earth, atmospheric temperatures decrease with altitude, and that cool air chills land surfaces at high elevations. When a moist wind moves toward and over a mountain on Earth, its water vapor cools and condenses, forming clouds and snow, as seen on mountaintops like the Alps.

But on Pluto, the opposite occurs. The dwarf planet’s atmosphere actually gets warmer with altitude because methane gas absorbs solar radiation. However, the atmosphere is too thin to affect surface temperatures, which remain constant with altitude. And unlike the way winds tend to ride up over mountains on Earth, the winds on Pluto mostly travel downslope.

“It is particularly remarkable to see that two very similar landscapes on Earth and Pluto can be created by two very dissimilar processes,” said Tanguy Bertrand, a postdoctoral researcher at NASA’s Ames Research Center and lead author on the paper. “Though theoretically objects like Neptune’s moon Triton could have a similar process, no other place in our solar system has ice-capped mountains like this besides Earth.”

To understand how similar landscapes develop from different conditions and chemistries, the researchers at the Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique (France) developed a three-dimensional model simulating the atmosphere and surface of Pluto. They found that the dwarf planet’s atmosphere has more gaseous methane at its warmer, higher altitudes. That gas can saturate, condense, and then freeze directly on mountain peaks without any clouds forming. At lower altitudes on Pluto, there is no methane frost because there is too little methane for condensation to occur.

This condensation process not only creates methane ice caps on Pluto’s mountains, but also similar features on its crater rims as well. The mysterious bladed terrain found in the Tartarus Dorsa region around Pluto's equator can also be explained by this cycle.

“Pluto really is one of the best natural laboratories we have to explore the physical and dynamic processes involved when compounds that regularly transition between solid and gas states interact with a planetary surface,” said Bertrand. “The New Horizons flyby revealed astonishing glacial landscapes we continue to learn from.”

NASA Earth Observatory image by Lauren Dauphin, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS/LANCE and GIBS/Worldview. Pluto imagery courtesy of NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute. Story by Frank Tavares, NASA Ames, with Mike Carlowicz.