After months of unusually heavy rain, thousands of people in Kenya’s Great Rift Valley have evacuated due to intense flooding. Rising waters have inundated homes, businesses, farms, and even entire islands. The torrential rains have also caused two important lakes to swell, creating several issues for local wildlife and businesses.

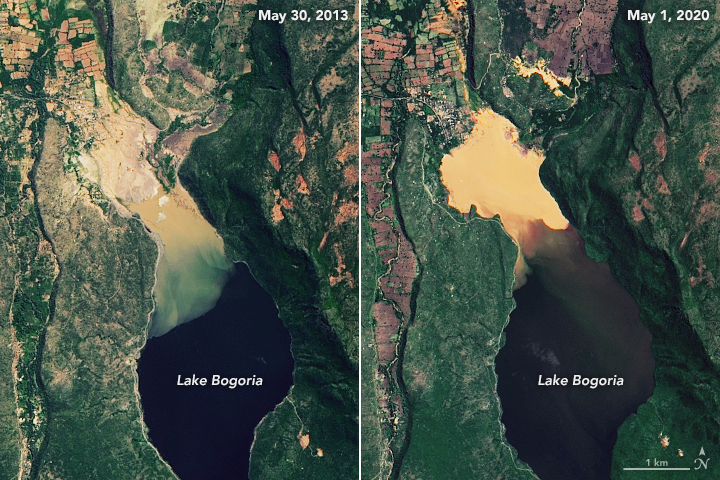

The natural-color images above show water levels on the south end of Lake Baringo on May 30, 2013 (left) and May 1, 2020 (right). The images below show flooding on the north end of Lake Bogoria, located less than 15 kilometers (10 miles) south of Lake Baringo. The images were acquired by the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8. Waters shaded brown and tan have heavy loads of suspended sediment.

The water levels of both lakes have been rising in recent years, but they have been particularly high in 2020. The senior warden for the Kenya Wildlife Service told Reuters that the area of Lake Baringo has expanded by 60 percent in the past seven years; it now covers 270 square kilometers (105 square miles). Lake Bogoria has swollen by 25 percent, now covering 43 square kilometers (17 square miles).

Both lakes play significant roles in sustaining local citizens, attracting tourists, and providing a home for many wildlife species. Lake Baringo provides irrigation and drinking water and is also home to Nile crocodiles. Rising waters at the lake have damaged businesses, schools, homes, and hotels, while bringing crocodiles and hippos dangerously close to people. Lake Bogoria is a World Heritage site and home to hundreds of bird species, including as many as one million flamingos at times. It also contains several geysers and hot springs that are popular with tourists; nearly 80 percent of these hot springs are now underwater.

Officials are particularly concerned that the freshwater Lake Baringo and alkaline Lake Bogoria could merge soon, which would cause cross-contamination and threaten wildlife even more. The two lakes were once 20 kilometers (13 miles) apart, but now sit 13 kilometers (8 miles) from one another. Neither lake has an outlet to allow excess water to flow out.

Editor’s note: Due to the persistent rain and the frequent midday cloudiness of nations around the equator, the images from May 2020 are the most recent clear views of the flooded areas acquired by Landsat satellites.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Kasha Patel.