Less than two months into hurricane season, the Atlantic basin has already produced six named storms, delivering some of the earliest activity in the past fifty years. None of the storms reached hurricane intensity, but the sheer number of them fit with forecasts of a busy season.

Forecasters at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center predicted in May that 2020 would likely be an above-average hurricane season. A typical year brings 12 named storms (winds of at least 63 kilometers/39 miles per hour), of which 6 become hurricanes (winds of at least 120 kilometers/74 miles per hour). This year, forecasters predicted 13 to 19 named storms, of which 6 to 10 would become hurricanes. Storm formation and intensification depend on a number of complex variables and conditions, and several are lining up in favor of robust activity in 2020.

“Early season storm activity does not necessarily correlate with later hurricane activity,” said Jim Kossin, an atmospheric scientist with NOAA. “But if we’re in a season where the environment is conducive to storm formation early on, then those underlying favorable conditions often persist throughout the season.”

Sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic Ocean have been abnormally warm so far in 2020, which could help fuel storms. Warm ocean water evaporates and provides moisture and energy for the lower atmosphere. As water vapor rises and condenses, it releases heat that warms the surrounding air and can promote the growth of storms. Ocean waters typically need to be above 27°C (80°F) for storms to develop. In early July, parts of the Atlantic basin (which includes the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean) hit temperatures of 30°C (86°F).

The map above shows sea surface temperatures on July 14, 2020. The map below shows sea surface temperature anomalies for the same day, indicating how much the water was above or below the long-term average (2003-2014) temperature for July 14. The data come from the Multiscale Ultrahigh Resolution Sea Surface Temperature (MUR SST) project, based at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. MUR SST blends measurements of sea surface temperatures from multiple NASA, NOAA, and international satellites, as well as ship and buoy observations.

“If it’s warmer than average for several months, it’s reasonable to say that it will still be warmer than average later on in the season,” said Tim Hall, a hurricane researcher at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies. “Ocean temperatures do not change rapidly.”

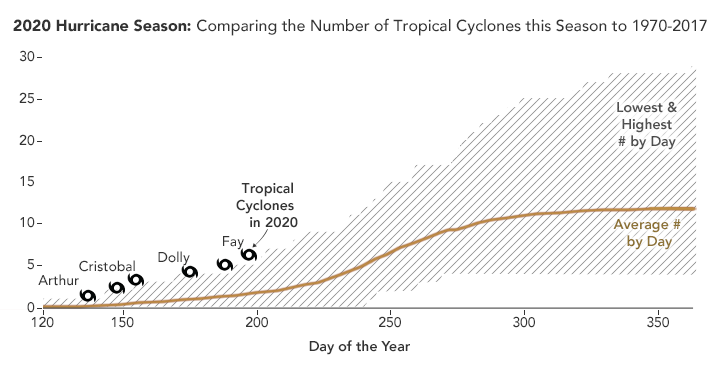

Hall compiled the data for the chart below, which shows how this season compares so far to the past 50 years. The brown line represents the average number of tropical cyclones from 1970-2017 for that day, calculated from the National Hurricane Center’s HURDAT2 database. Day 120 is April 30 (except in Leap Years), one month before the official start of the season. The crest and trough of the shading represent the highest and lowest accumulated tropical cyclone count on that day. The season with the overall highest count was 2005, when there were 30 named storms and four category 5 hurricanes (Emily, Katrina, Rita, and Wilma).

“2020 is leading the pack in the number of tropical storms so far,” said Hall. The fifth and sixth named tropical storms of 2020—Eduoard and Fay—occurred earlier than any other in the five decades of satellite observations. Hall is quick to note, however, that the coastal impacts of the storms have been relatively mild, as no storm strengthened into a hurricane.

Beyond a warm ocean, a combination of factors also need to line up in order to create strong storms. Kossin noted that storms need low vertical wind shear and moist air in order to form, intensify, and persist. Vertical wind shear arises from changes in wind speed or direction between Earth’s surface and the top of the troposphere (10 kilometers/6 miles above sea level). Strong vertical wind shear can impede storm formation by removing heat and moisture from the atmosphere. It can also up-end the shape of a hurricane by blowing its top away from its bottom.

Forecasters have noted the development of one phenomenon that may affect wind shear in 2020: La Niña. Characterized by unusually cold ocean surface temperatures in the eastern equatorial Pacific, La Niña weakens westerly winds high in the atmosphere. This leads to low vertical wind shear in areas around the Americas, including the Atlantic basin, allowing hurricanes to form.

On the other hand, bursts of dry air from the Sahara can suppress storm formation. Since June 2020, Saharan dust storms have carried dry air across the Atlantic Ocean and stunted storm development.

“Even when the oceans are very warm and favorable for storm formation, dry air intrusions and dusty air from the Sahara can keep hurricanes from forming,” said Kossin. Saharan air layers create strong wind shear and bring dry air to the mid-levels of the atmosphere, where it can affect the structure and development of tropical cyclones.

But unlike ocean temperatures, atmospheric conditions like wind shear and dry air can change rapidly. “We had events that suppressed further intensification of the tropical storms so far, but that doesn't mean those events will still be around in August and September," said Hall. "The warmer-than-average ocean temperatures will likely persist until the fall so the table is set for an active season if these other key factors also line up.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using data from the Multiscale Ultrahigh Resolution (MUR) project. Chart data courtesy of Tim Hall. Story by Kasha Patel.