In southern South America, clouds often rule the skies. But in June 2020, just the right weather patterns were in place to provide a rare, clear view of Patagonia in winter.

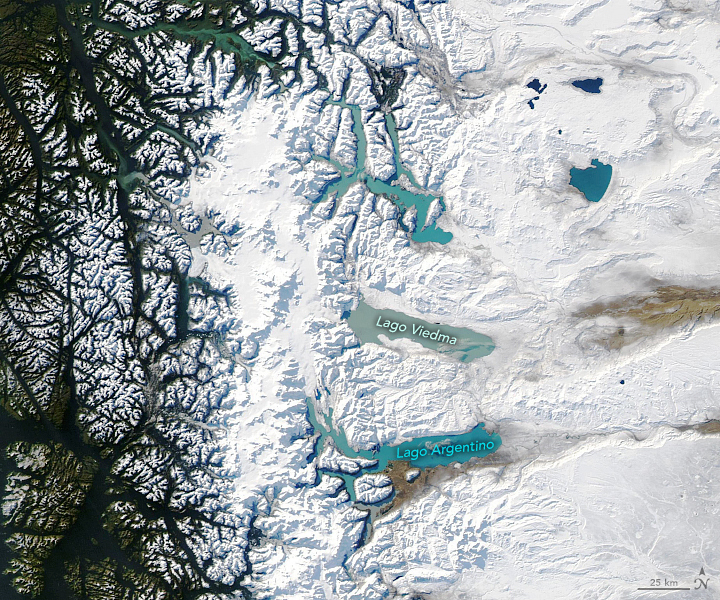

On June 26, when the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite acquired these images, skies were clear over nearly all of Patagonia, which spans more than 1 million square kilometers of the continent’s southern end. Snow cover is visible from the western slopes of the Andes Mountains in Chile to the coastal lowlands in Argentina.

According to René Garreaud, a professor at the University of Chile, it’s unusual to see such a widespread cloud-free area over Patagonia. “The last time that I saw a completely clear image was in February 2019,” he said. At that time, during the Southern Hemisphere’s summer, the warm seasonal temperatures meant snow and ice were mostly limited to the spine of the Andes and the Patagonian icefields.

The region is typically cloudy in satellite imagery due to the year-round passage of storms. The southern tip of the continent dips into a belt of prevailing westerly winds, along which high- and low-pressure systems constantly drift eastward. The terrain also enhances the region’s cloudiness: when winds encounter the Andes, moist air blowing in from the Pacific Ocean is forced upward, where it cools and condenses into clouds.

In June, the usual weather pattern came to a halt. A system of high pressure settled in over the Drake Passage—the waterway just south of the continent—and brought clear skies to the wider region. The weather system stayed put for nearly a week. The phenomenon is known as a “blocking high,” aptly named because it blocks the typical movement of air masses. In this case, westerly winds were forced to take a detour.

As a result of the blocking high, unusually cold temperatures stretched from Patagonia all the way to Paraguay and Bolivia. Cloud-free skies mean that heat near the land surface can more easily escape to space, resulting in cooler temperatures. In addition, the diverted westerly winds brought cold air from Antarctica and funneled it right into southern Patagonia.

Those cold temperatures kept the Patagonian plateau in Argentina blanketed under snow that fell during a major storm on June 23-24. Parts of the southern Andes receive abundant precipitation each year, measuring more than 500 centimeters (200 inches). It’s less common, however, to see snowfall so far east on an arid part of the continent that receives less than 30 centimeters (12 inches) of precipitation each year.

The bout of frigid air, however, was not enough to freeze the deep lakes east of the icefield (detailed image). “Even in winter, surface air temperatures are generally above 0 degrees C.,” Garreaud said. “So the cold event was intense, but not long enough to freeze these lakes.” Left unfrozen, the lakes’ turquoise color—a result of “glacial flour”—contrasts even more with the surrounding white snow.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS/LANCE and GIBS/Worldview. Story by Kathryn Hansen.