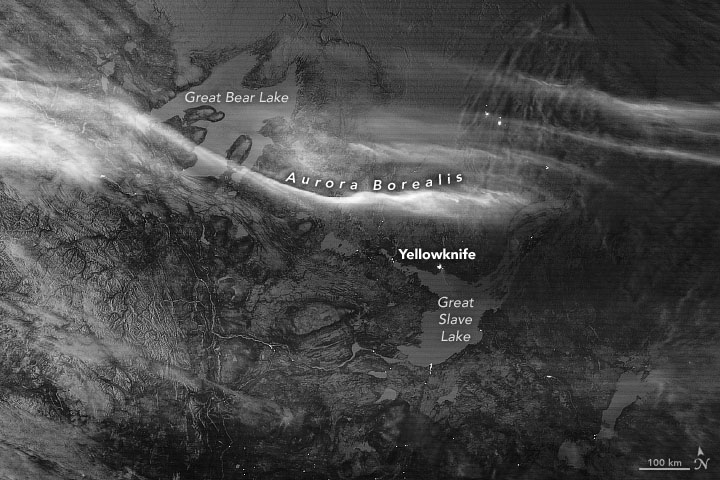

On February 4, 2020, the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the NOAA-NASA Suomi NPP satellite acquired these images of the northern lights over northwestern Canada. The combination of light from the aurora and from the waxing gibbous Moon (between the first quarter and full)—along with the reflections from bright snow and ice on the mountains and lakes—gives the landscape extra visual definition for a nighttime shot.

The image was acquired through the use of the VIIRS day-night band (DNB), which detects light in a range of wavelengths from green to near-infrared and uses filtering techniques to observe signals such as city lights, auroras, wildfires, and reflected moonlight. Since the launch of Suomi NPP in late 2011, scientists have been using VIIRS to provide unprecedented views of Earth at night (see our gallery here).

“The DNB, simply stated, brings the day to the night in the sense that it can use moonlight in the same way conventional daytime visible sensors use sunlight,” said Steven Miller, a Colorado State University researcher who works regularly with nighttime imagery.

The day-night band has particular value for people at high latitudes, such as the area featured in this image. “Detecting and tracking sea ice at high latitudes and snow fields at mid-latitudes in the winter months, via moonlight, has proved a strong suit of the DNB. It has been a hit with forecasters in Alaska and northern Canada as they face those long, dark nights,” Miller said. Many weather satellites are situated in geostationary orbit over the equator, and the polar regions are far off on the fringes of what they can see. But the polar-orbiting Suomi NPP can provide multiple observations and measurements per day of moonlit clouds, sea ice, snow cover, and open waterways for people whose winter nights can last for months.

The VIIRS sensors on Suomi NPP and the NOAA-20 satellite (launched in 2017) succeed and improve upon 40 years of night lights data from the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP). VIIRS DNB can distinguish night lights with six times better spatial resolution and 250 times better lighting resolution (dynamic range) than past military satellites. And because Suomi NPP and NOAA-20 are civilian satellites, the data are available to scientists and the public within minutes to hours of acquisition.

According to Miller, at least 500 peer-reviewed journal papers have been published based on DNB data, with another 120 combining DNB data with the older DMSP observations. Subject areas have included social science (often demography and economics), atmospheric composition, civil engineering, biology, and natural resource monitoring and management. Nighttime imagery is particularly useful for weather forecasters and for emergency response and relief agencies working in the wake of natural disasters.

Beyond the practical, nighttime imagery is simply awe-inspiring. “We can see the beauty of civilization as a web of lights sprawling across the globe, connecting us, sometimes separating us, and always reminding us that we are all inhabitants of one planet,” Miller added. “The DNB allows us to see ourselves—our accomplishments, our tragedies, our strengths and vulnerabilities, and our existence as part of the Earth’s biosphere—in an unprecedented way.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using VIIRS day-night band data from the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership. Story by Michael Carlowicz.