Austral summer is a popular time for hikers to tramp across the stunning New Zealand back country. But this year in the mountains of South Island, there are hints of events unfolding 2,000 kilometers away. Carried by the wind, dust and ash particles from Australia have painted some glaciers in New Zealand with a brown-orange tint.

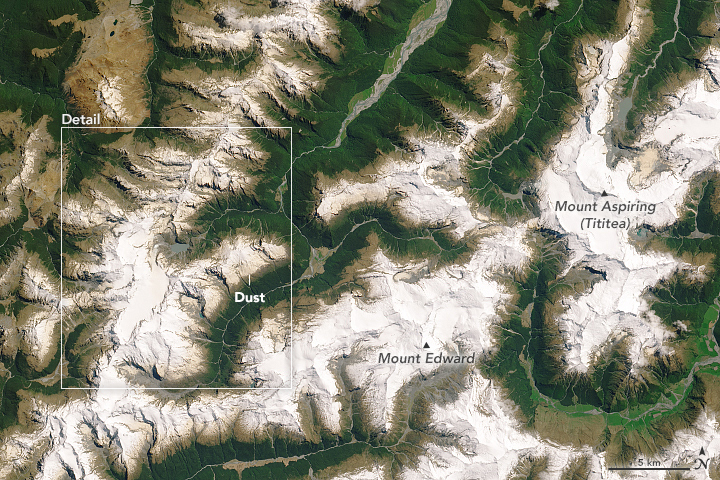

The natural-color image pair above, acquired with the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8, shows areas of dirty snow and ice in New Zealand’s Southern Alps. The right image was acquired on November 11, 2019, during an extremely hot and dry season in eastern Australia. For comparison, the left image shows the same area on December 15, 2014, during a more typical year.

The images show part of Mount Aspiring National Park, a mountainous and glaciated wilderness at the southern end of the Southern Alps. The image below shows a wide view of the region, including the park’s tallest mountain and namesake, Mount Aspiring (called Tititea by the Māori). Ancient glaciers carved the mountain into a pyramid shape, the peak of which now towers 700 meters above the park’s largest modern glaciers—the Bonar, Therma, and Volta. More than 100 other glaciers dot the region. Many appear at least partly covered with the colorful particles.

According to Andrew Mackintosh, a glaciologist at Monash University, the brown-orange color is likely dust from soil erosion in Australia. Particles rich in iron oxide are lofted into the air during Australia’s dry summers and carried by winds across the Tasman Sea.

Hamish McGowan, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Queensland, agrees that the source of the color is dust. “Australian dust on New Zealand snowfields is relatively common,” McGowan said. He notes that previous analyses of samples collected from New Zealand glaciers have shown that the dust typically comes from New South Wales, northwest Victoria, South Australia, and occasionally from western Queensland.

November was unusually early for New Zealand glaciers to be covered with so much dust. Accumulations usually peak late in the austral summer, after months of dry weather in Australia and little fresh snow in New Zealand. Years with severe drought can make the dust more abundant. Indeed, Australia has seen exceptionally hot and dry conditions in 2019; the country’s annual mean temperature was reported to be the hottest on record.

Some of the color on the glaciers is also likely to be black carbon—tiny soot-like particles that rise into the atmosphere when bushfires burn through wood, vegetation, and other materials. Models have shown that ample amounts of black carbon have blown eastward from Australia during the devastating fire season. These particles tend to make a much darker discoloration of the snow. The relative proportion of dust and soot particles at the time of the Landsat images is unknown.

“I would expect that the layers seen in the November 11 image will be some sort of combination of particles,” said Heather Purdie, a glaciologist at the University of Canterbury. “It had an orange-brown color, so maybe more dust, less ash, compared to what is arriving this week.”

Pink areas spotted on some of the glaciers could have a different source entirely. “It’s possible that the pink is algae or something else that is growing from the nutrients in the dust and soot,” Mackintosh said. Purdie agrees, noting that “snow algae” is relatively common. “I saw a large area of this on some remaining seasonal snow on Mount Enys (Craigieburn Range) just last week.”

Purdie and other researchers use end-of-summer dust layers to estimate how much snow has accumulated on the glaciers each year. “During the annual monitoring trip to Rolleston glacier in late November, there was already a distinctive orange-brown layer visible in the snow pack,” Purdie said. “I expect that by the end of summer this year the layer will be quite distinctive due to the volume of ash and dust arriving.”

Scientists will wait until March (end of summer) to determine how the dark-colored particles have affected the glaciers’ mass balance; that is, whether the glaciers have had a net gain or net loss of ice. Gains come from the accumulation of snowfall. “We did get a lot of late-spring snow, so our glaciers went into summer in slightly better shape than they had the previous two years,” Purdie said. Conversely, melting can be enhanced by the presence of thin layers of dust or black carbon. Darkened surfaces reduce the amount of sunlight that is reflected, increasing the rate of melting.

“If dust and soot transport from Australia becomes more of a feature of our southern summers, this will likely lead to a quicker demise of New Zealand glaciers,” Mackintosh said, “which are already projected to lose most of their mass by the end of 2100.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Kathryn Hansen.