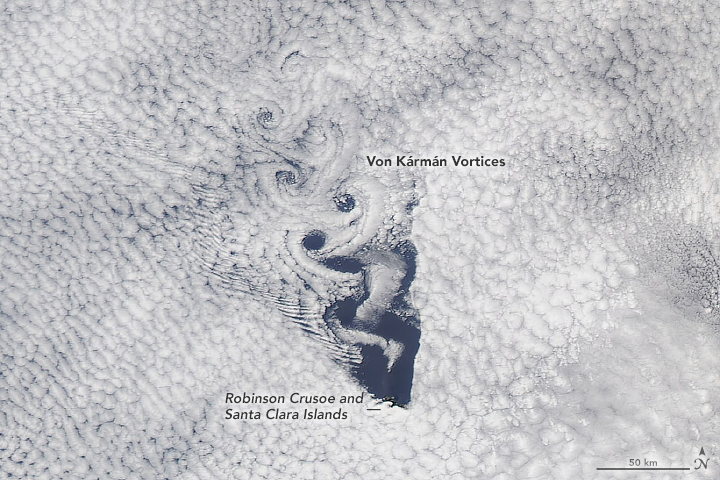

When swirls of clouds formed over the South Pacific Ocean, we couldn’t help but notice their heart-like shape. But fluid dynamics has a solid explanation for this Valentine in the sky.

The pattern is known as a von Kármán vortex, and the phenomenon occurs in a wide range of places around the planet. It forms when the flow of a fluid is diverted around a blunt object, imparting rotation in alternating directions along the object’s lee side. In this instance, the vortices were produced as winds were diverted around the Juan Fernández Islands, 670 kilometers (420 miles) off the coast of Chile.

Von Kármán vortices can form whenever there is strong air flow around a barrier, but they need clouds or smoke to become obvious to the human eye. On February 2, 2019, the rotating air produced swirls in a layer of marine stratocumulus. The disturbance that trailed behind the islands was visible in these images acquired by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite.

The vortices on the left size of the image line up behind Alejandro Selkirk, the largest of the Juan Fernández Islands. Rising 1,268 meters (4,160 feet) above sea level, it is also the tallest in the island group. The vortices to the right are behind a pair of islands in the Chilean archipelago—Robinson Crusoe and Santa Clara. The second image shows a detailed view of this island pair.

Other islands can produce the spiraling cloud patterns if conditions are right. An island must be tall enough to force enough air around it rather than over it. The formula also requires adequate and generally constant wind speeds low in the atmosphere, which is one reason why the spirals often form behind islands in the path of the trade winds. Check out these vortices that formed in recent years behind the Canary Islands, and the Guadalupe and Tristan da Cunha islands.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Kathryn Hansen, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS/LANCE and GIBS/Worldview. Story by Kathryn Hansen.