The world is literally a greener place than it was twenty years ago, and data from NASA satellites has revealed a counterintuitive source for much of this new foliage. A new study shows that China and India—the world’s most populous countries—are leading the increase in greening on land. The effect comes mostly from ambitious tree-planting programs in China and intensive agriculture in both countries.

Ranga Myneni of Boston University and colleagues first detected the greening phenomenon in satellite data from the mid-1990s, but they did not know whether human activity was a chief cause. They then set out to track the total amount of Earth’s land area covered by vegetation and how it changed over time.

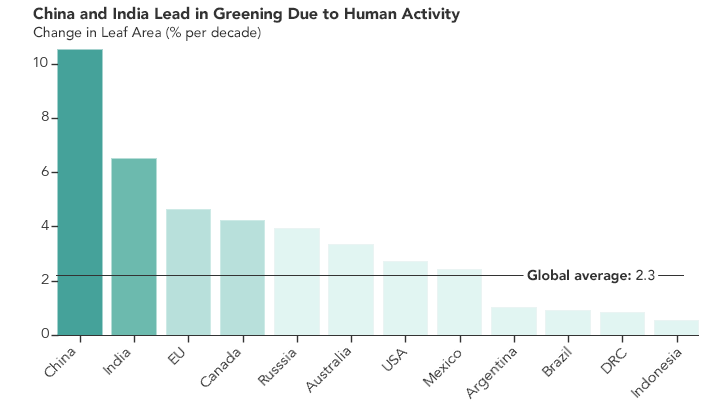

The research team found that global green leaf area has increased by 5 percent since the early 2000s, an area equivalent to all of the Amazon rainforests. At least 25 percent of that gain came in China. Overall, one-third of Earth’s vegetated lands are greening, while 5 percent are growing browner. The study was published on February 11, 2019, in the journal Nature Sustainability.

The maps on this page show the increase or decrease in green vegetation—measured in average leaf area per year—in different regions of the world between 2000 and 2017. Note that the maps are not measuring the overall greenness, which explains why the Amazon and eastern North America do not stand out, among other forested areas.

“China and India account for one-third of the greening, but contain only 9 percent of the planet’s land area covered in vegetation,” said lead author Chi Chen of Boston University. “That is a surprising finding, considering the general notion of land degradation in populous countries from overexploitation.”

This study was made possible thanks to a two-decade-long data record from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instruments on NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites. An advantage of MODIS is the intensive coverage they provide in space and time: the sensors have captured up to four shots of nearly every place on Earth, every day, for the past 20 years.

“This long-term data lets us dig deeper,” said Rama Nemani, a research scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center and a co-author of the study. “When the greening of the Earth was first observed, we thought it was due to a warmer, wetter climate and fertilization from the added carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Now with the MODIS data, we see that humans are also contributing.”

China’s outsized contribution to the global greening trend comes in large part from its programs to conserve and expand forests (about 42 percent of the greening contribution). These programs were developed in an effort to reduce the effects of soil erosion, air pollution, and climate change.

Another 32 percent of the greening change in China, and 82 percent in India, comes from intensive cultivation of food crops. The land area used to grow crops in China and India has not changed much since the early 2000s. Yet both countries have greatly increased both their annual total green leaf area and their food production in order to feed their large populations. The agricultural greening was achieved through multiple cropping practices, whereby a field is replanted to produce another harvest several times a year. Production of grains, vegetables, fruits and more have increased by 35 to 40 percent since 2000.

How the greening trend may change in the future depends on numerous factors. For example, increased food production in India is facilitated by groundwater irrigation. If the groundwater is depleted, this trend may change. The researchers also pointed out that the gain in greenness around the world does not necessarily offset the loss of natural vegetation in tropical regions such as Brazil and Indonesia. There are consequences for sustainability and biodiversity in those ecosystems beyond the simple greenness of the landscape.

Nemani sees a positive message in the new findings. “Once people realize there is a problem, they tend to fix it,” he said. “In the 1970s and 80s in India and China, the situation around vegetation loss was not good. In the 1990s, people realized it, and today things have improved. Humans are incredibly resilient. That’s what we see in the satellite data.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using data courtesy of Chen et al., (2019). Story by Abby Tabor, NASA Ames Research Center, with Mike Carlowicz, Earth Observatory.