Land surface temperature is how hot the “surface” of the Earth would feel to the touch in a particular location. From a satellite’s point of view, the “surface” is whatever it sees when it looks through the atmosphere to the ground. It could be snow and ice, the grass on a lawn, the roof of a building, or the leaves in the canopy of a forest. Thus, land surface temperature is not the same as the air temperature that is included in the daily weather report.

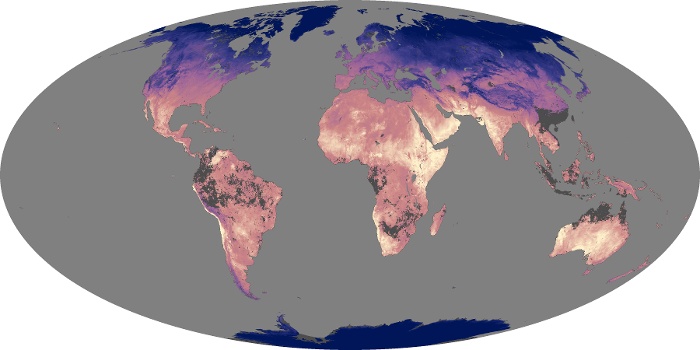

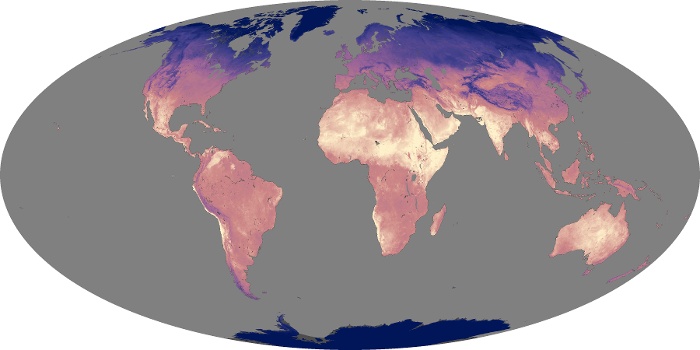

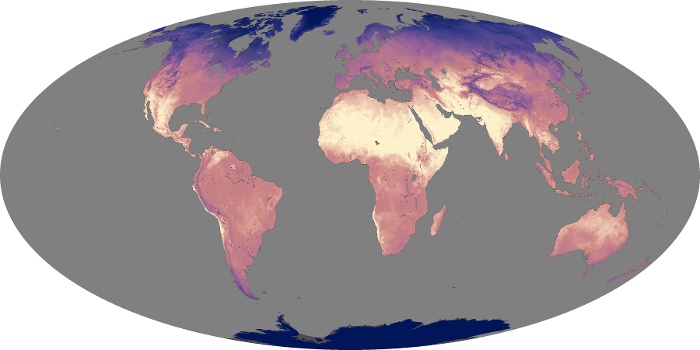

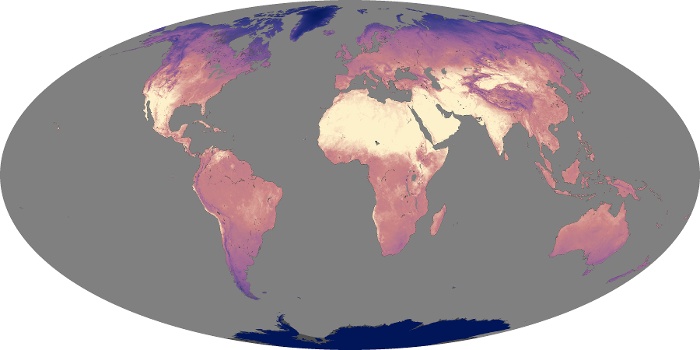

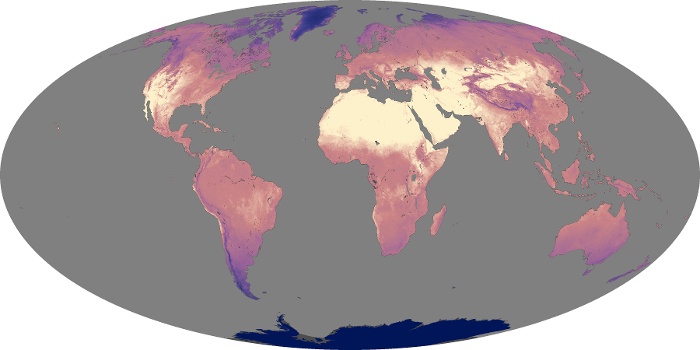

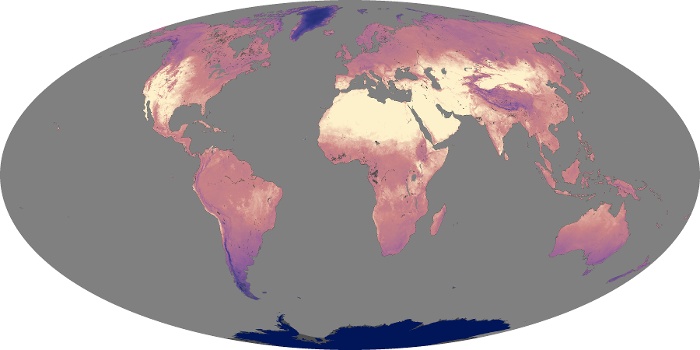

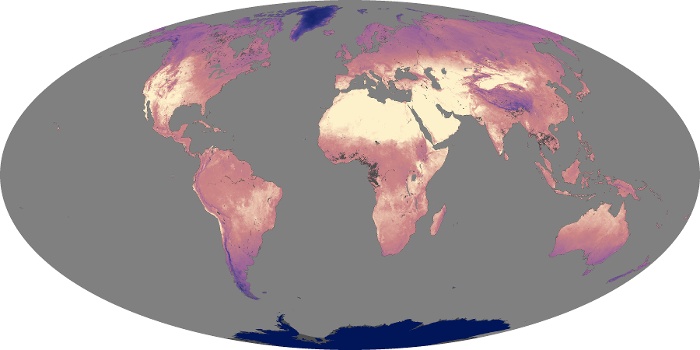

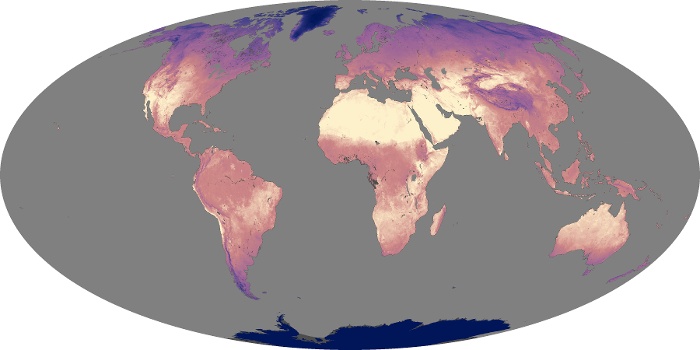

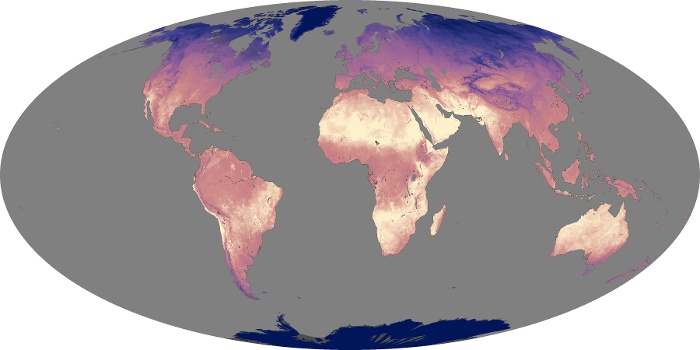

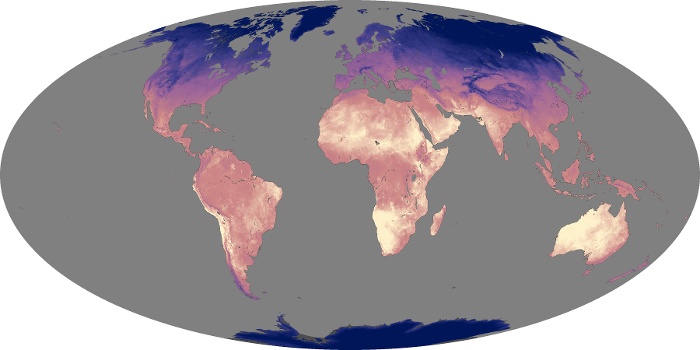

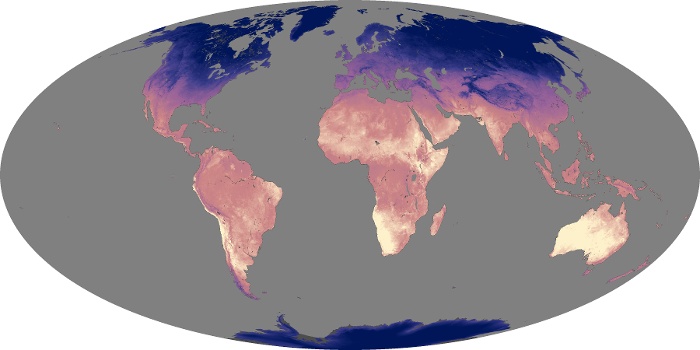

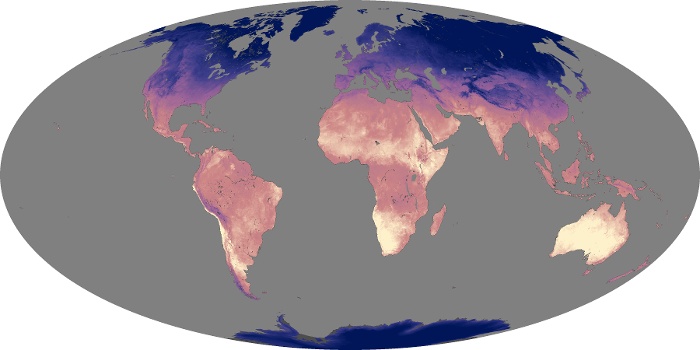

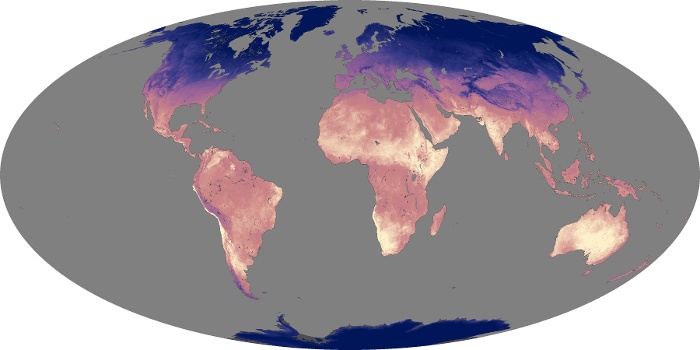

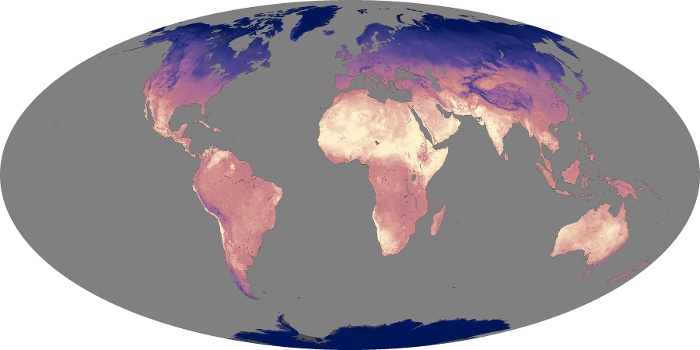

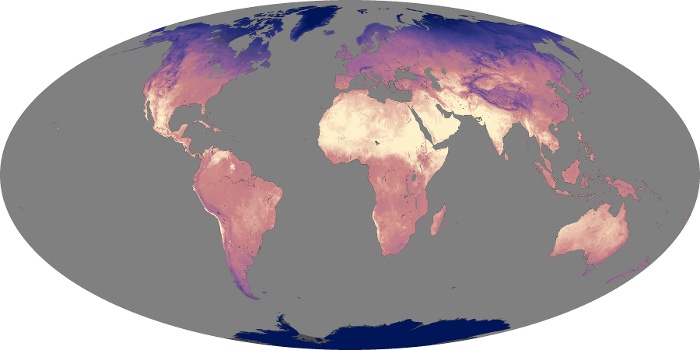

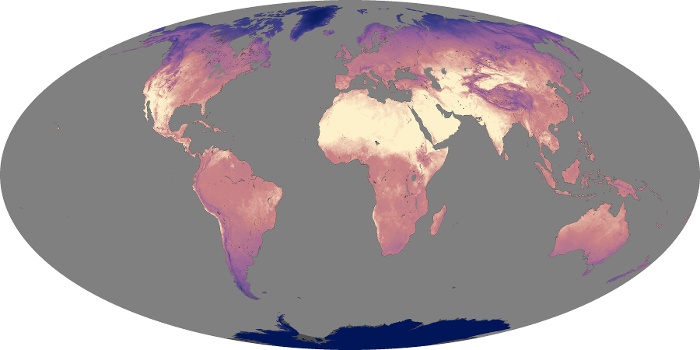

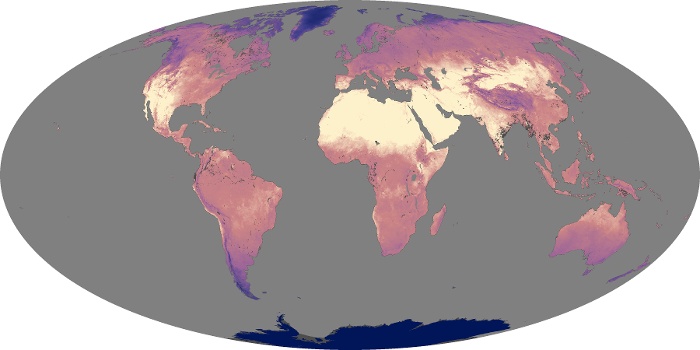

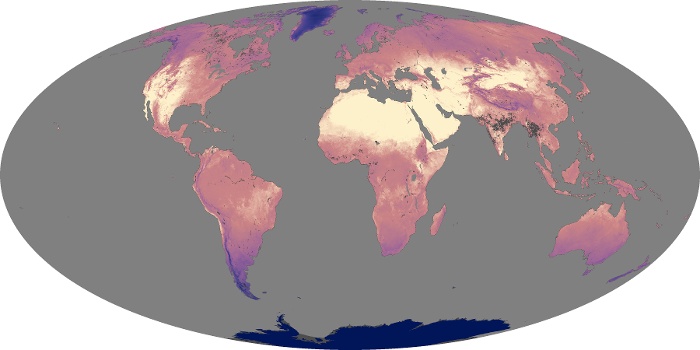

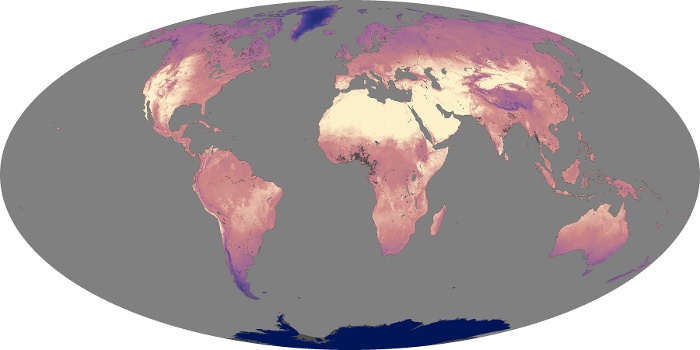

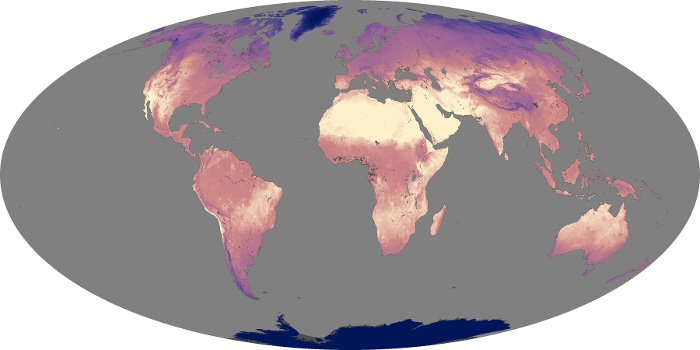

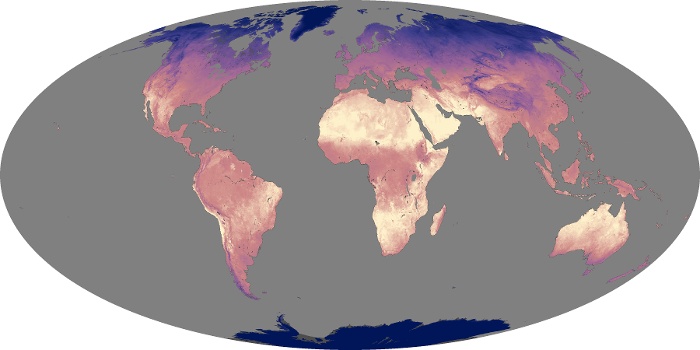

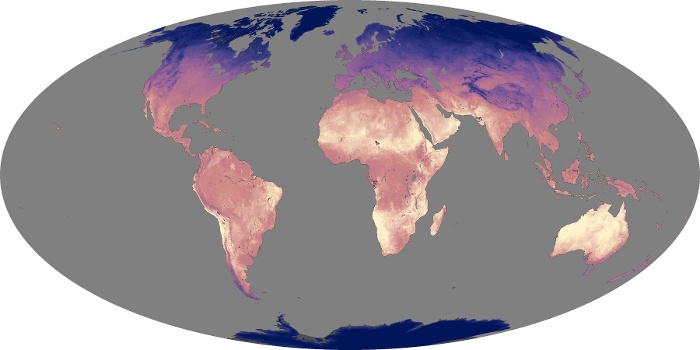

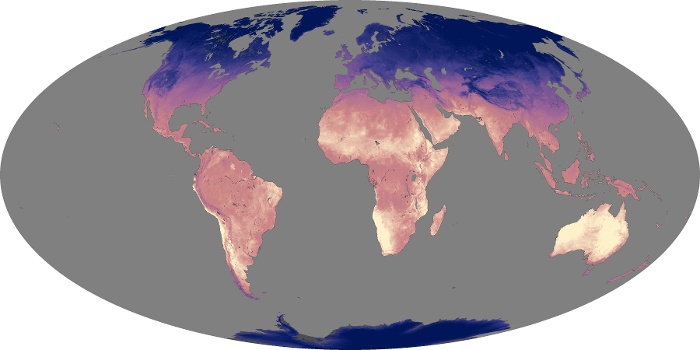

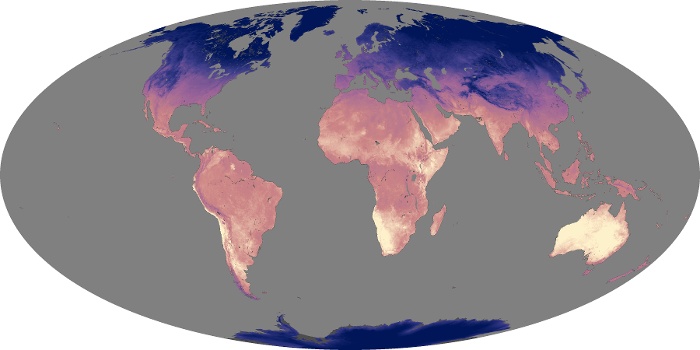

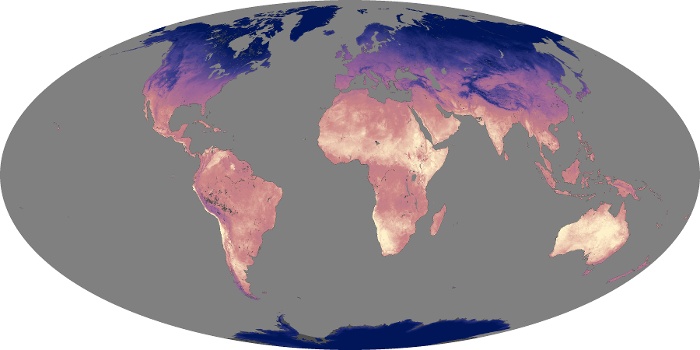

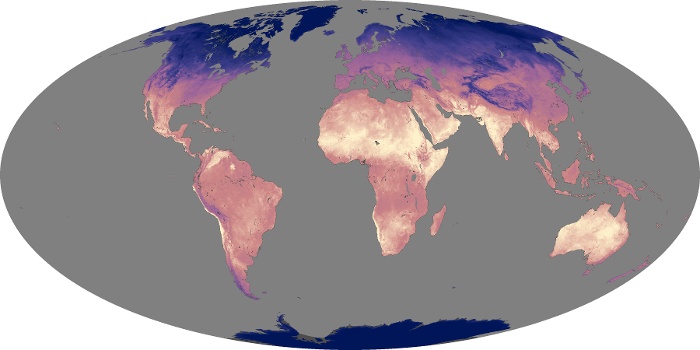

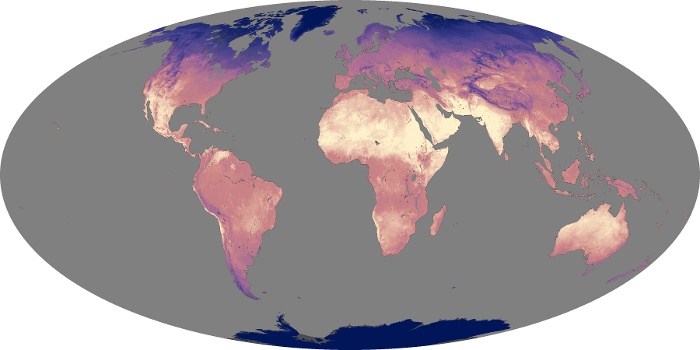

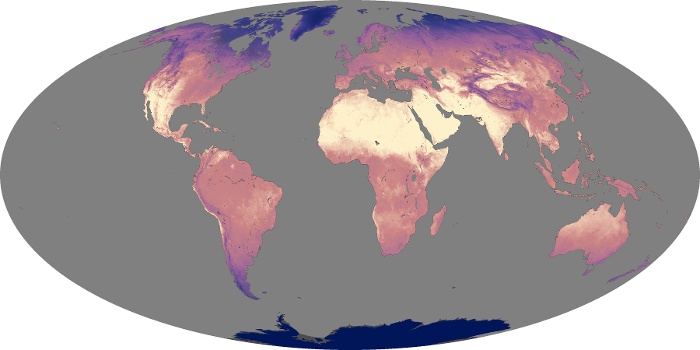

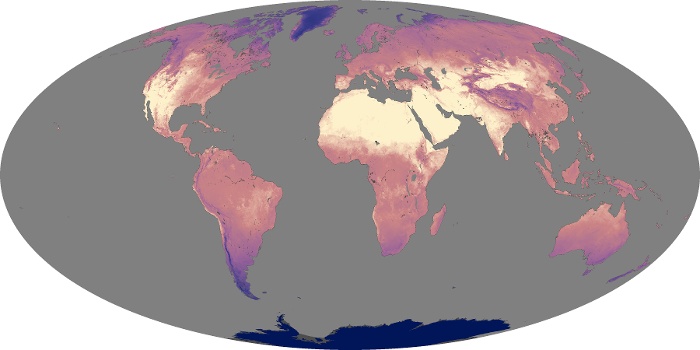

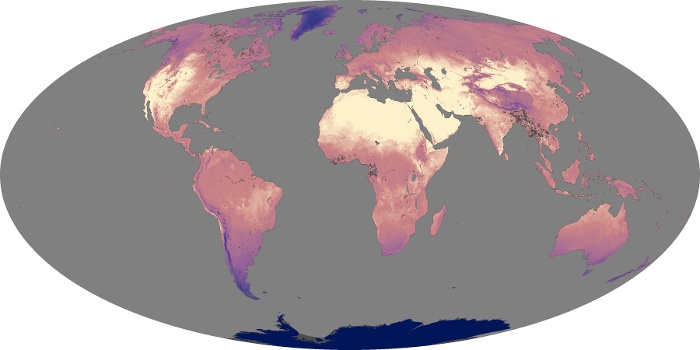

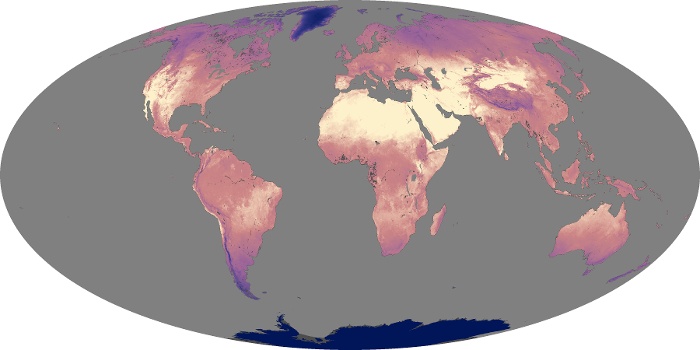

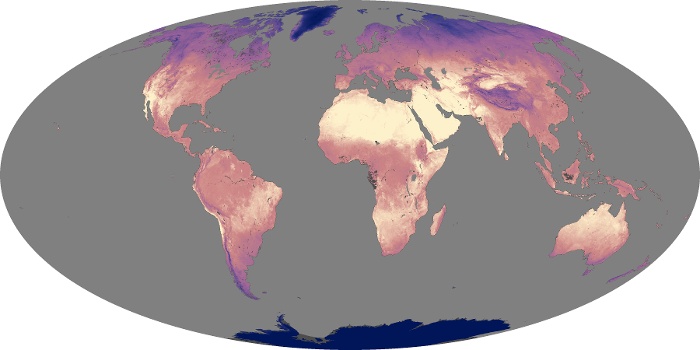

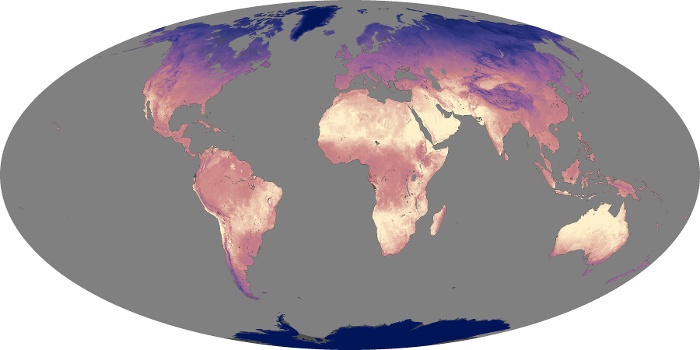

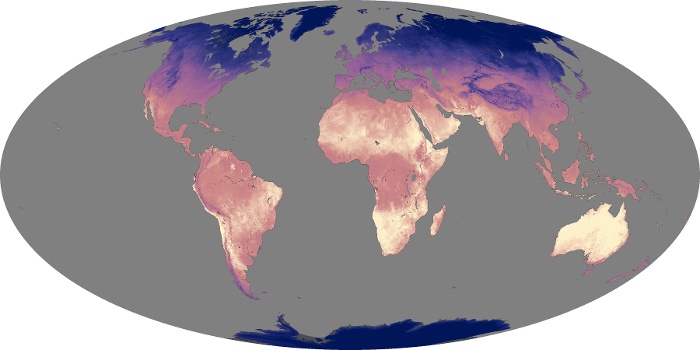

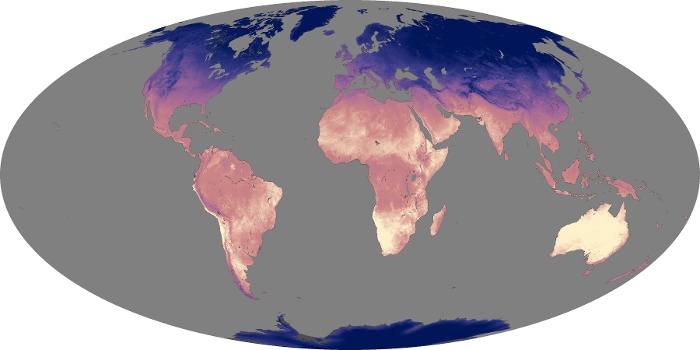

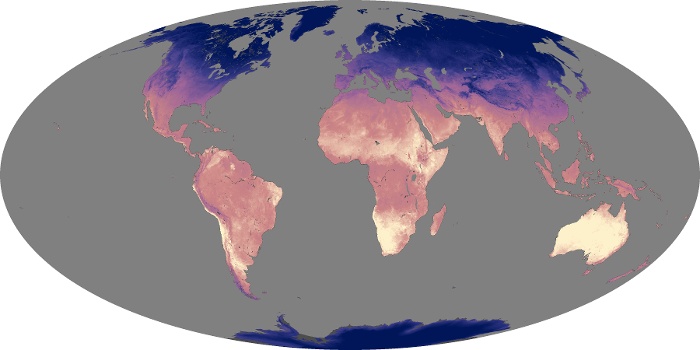

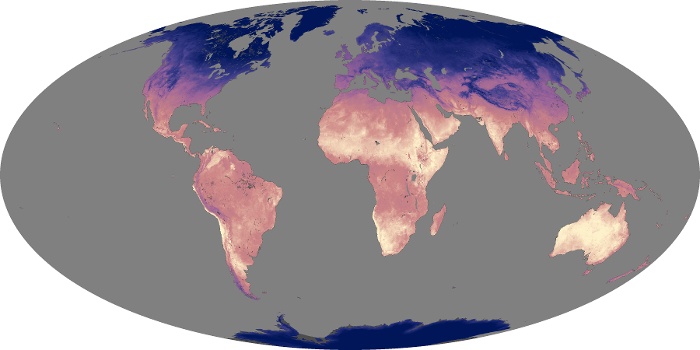

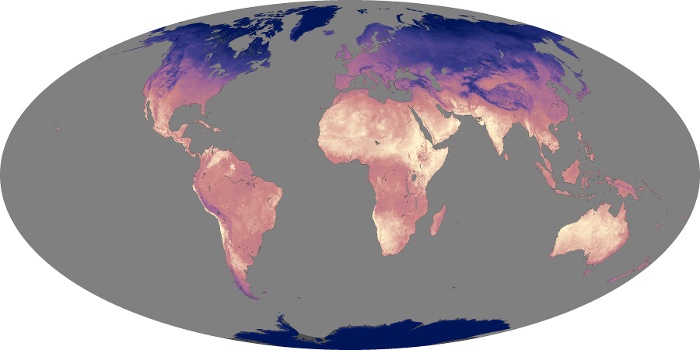

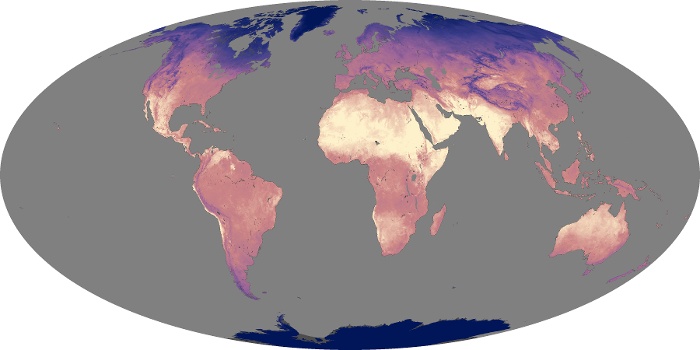

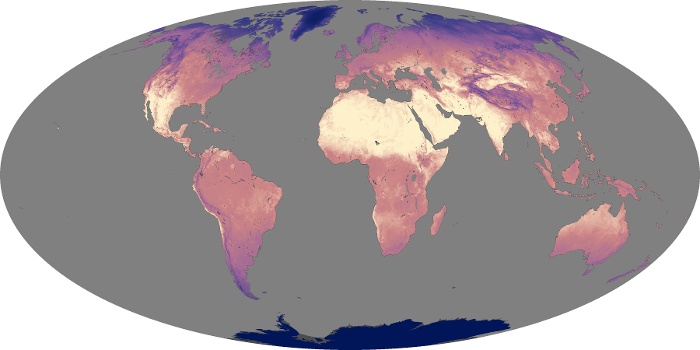

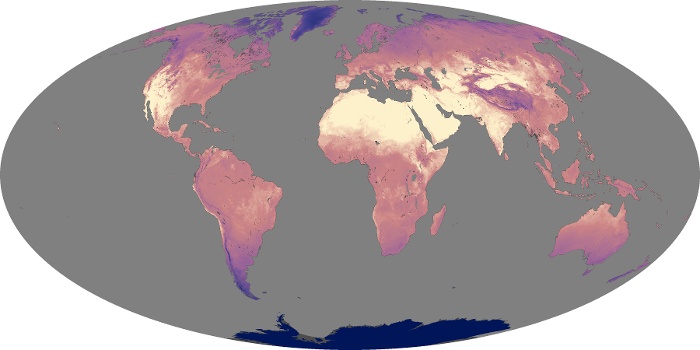

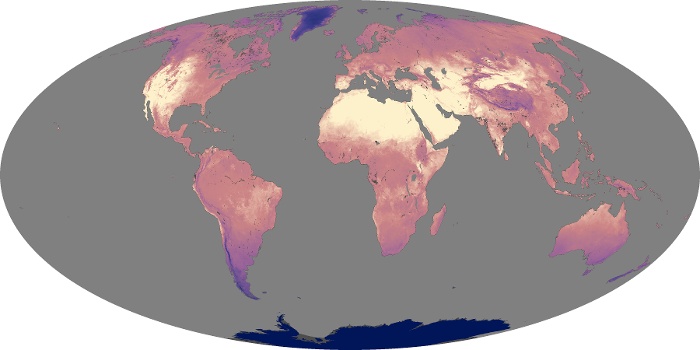

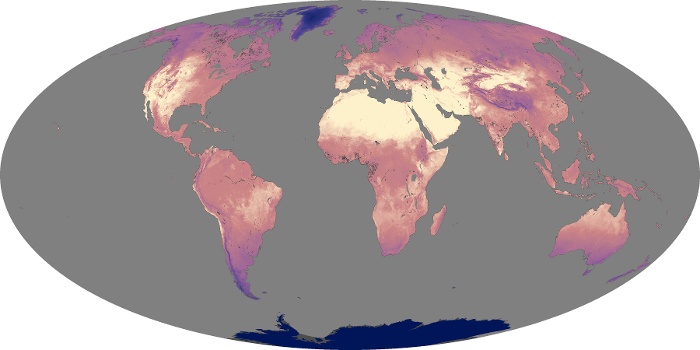

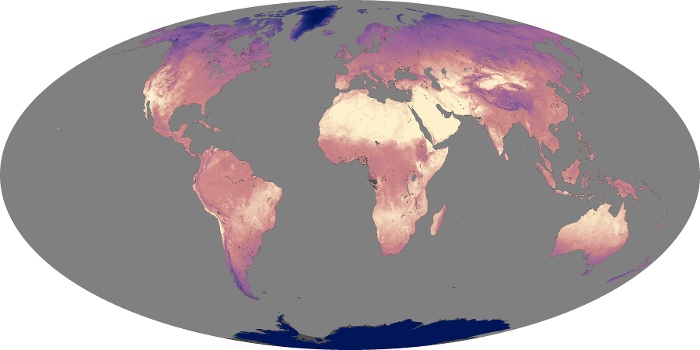

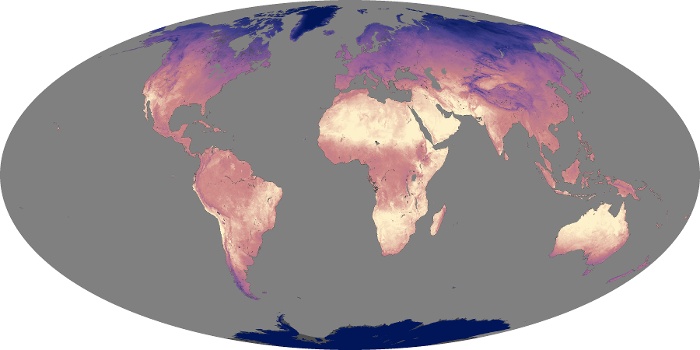

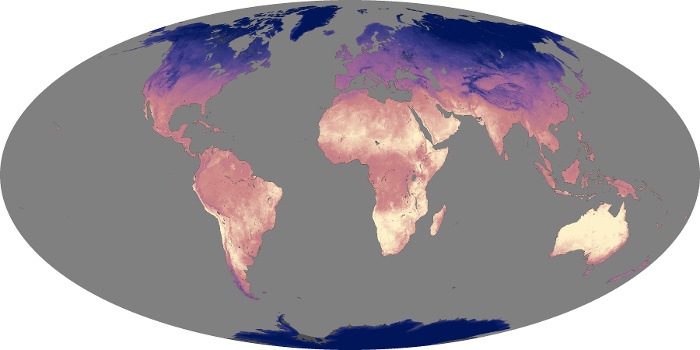

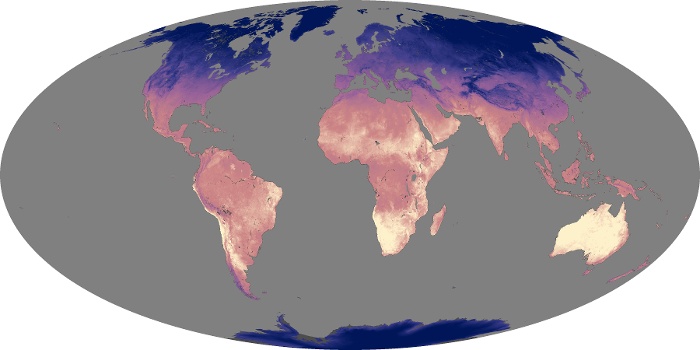

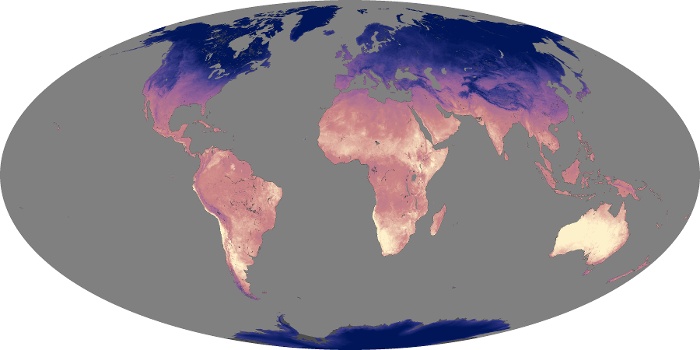

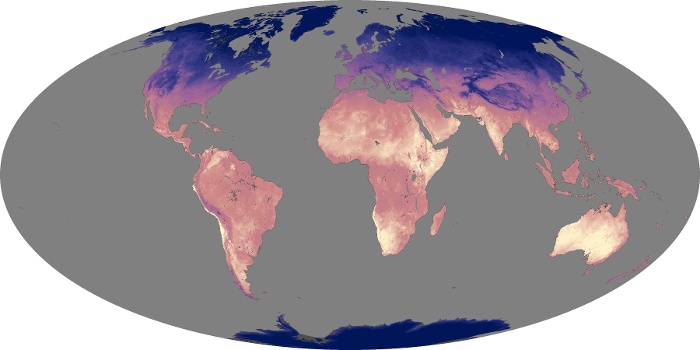

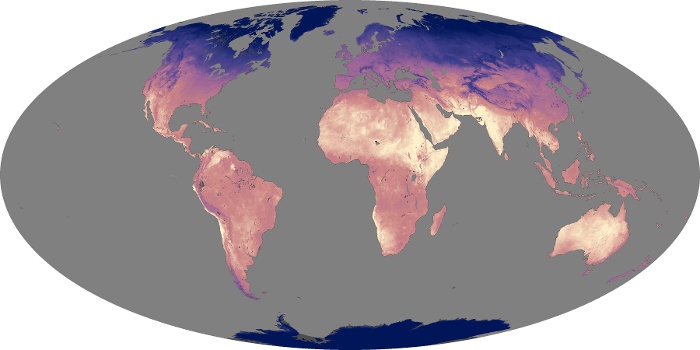

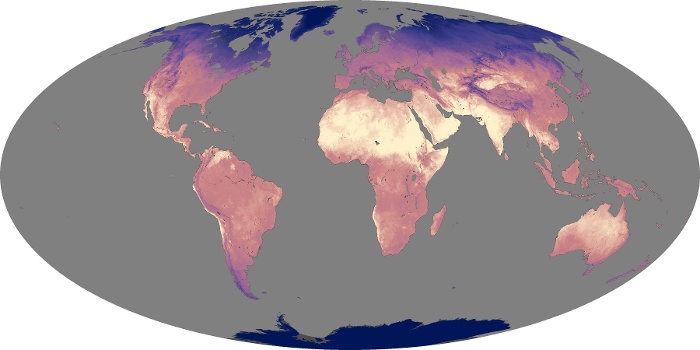

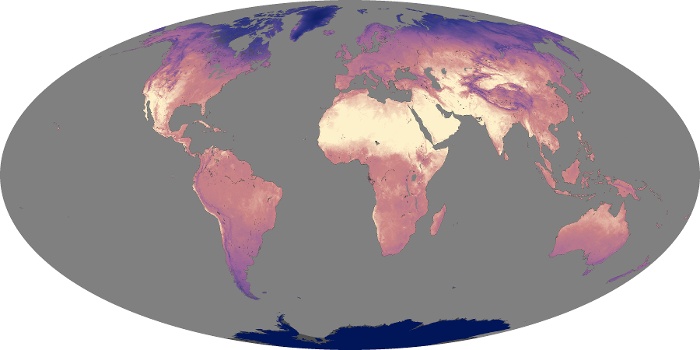

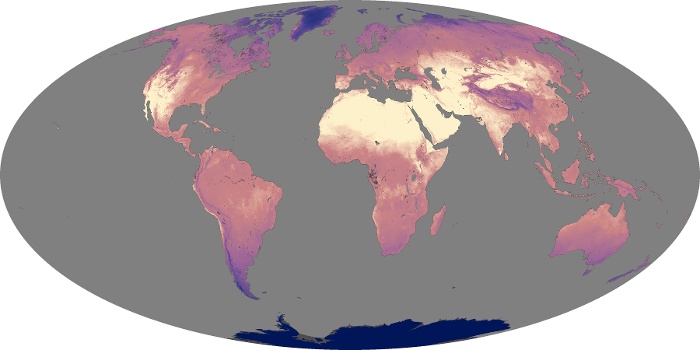

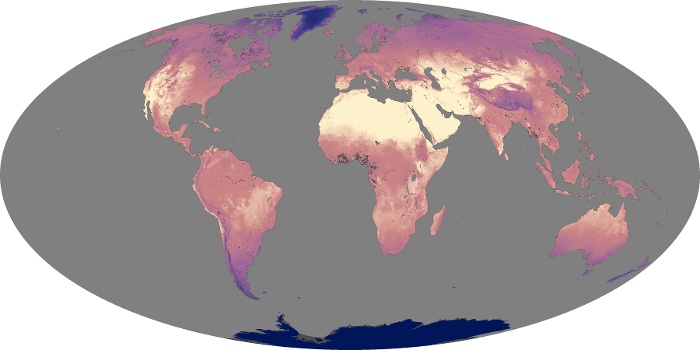

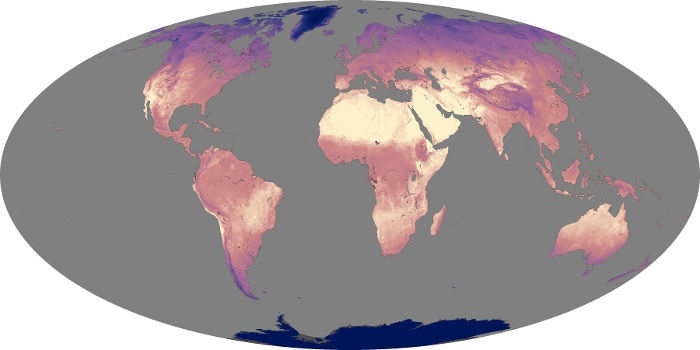

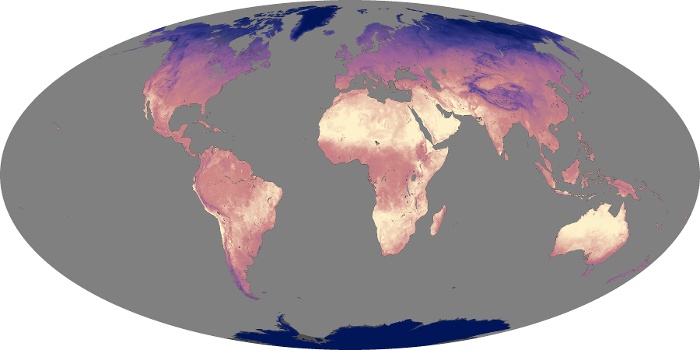

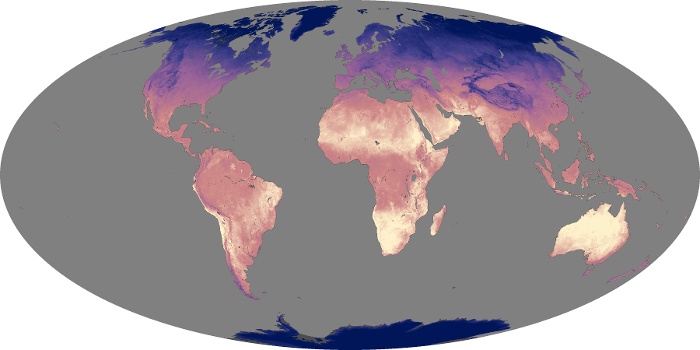

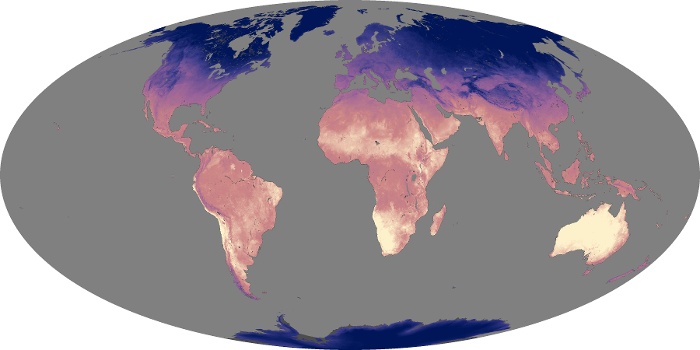

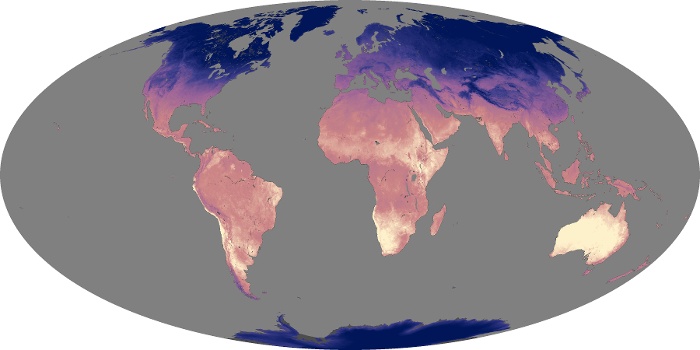

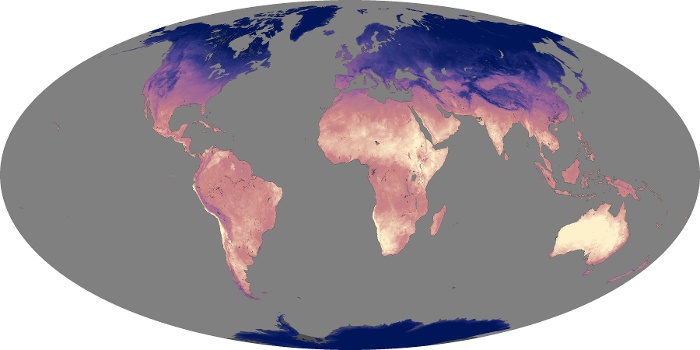

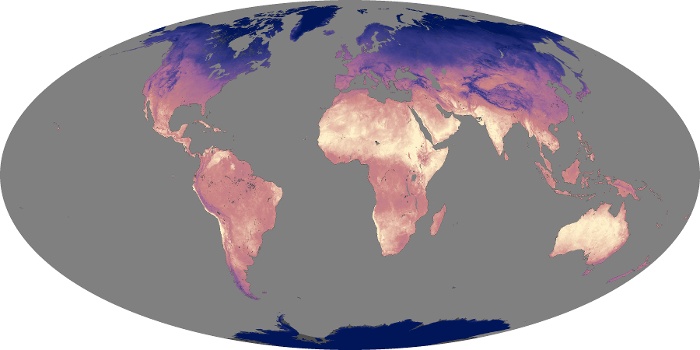

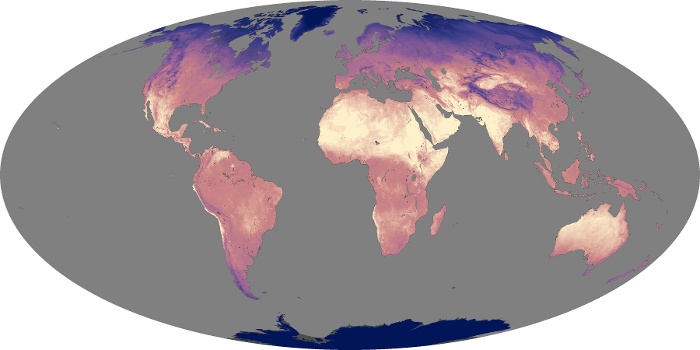

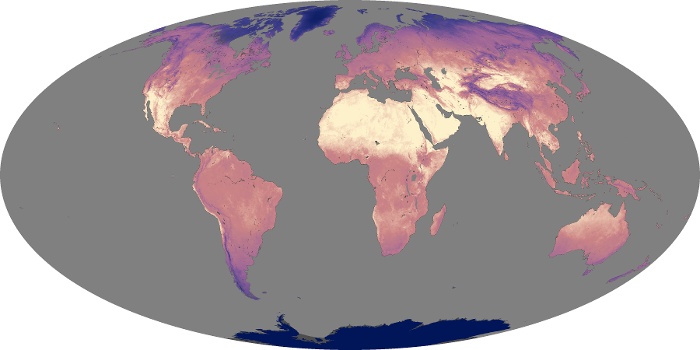

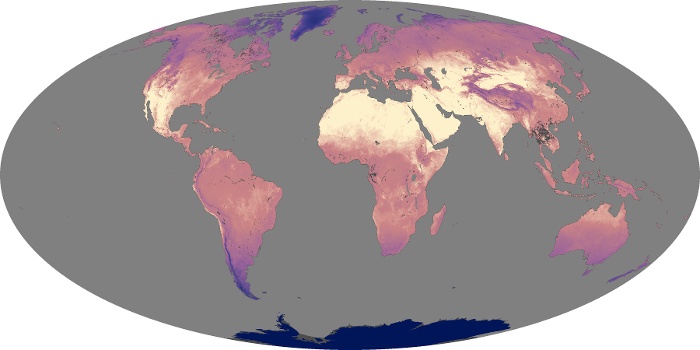

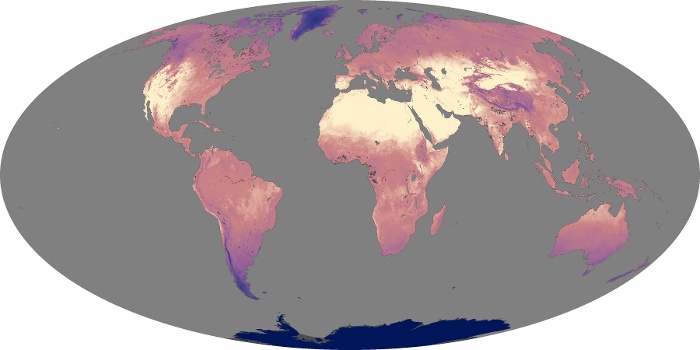

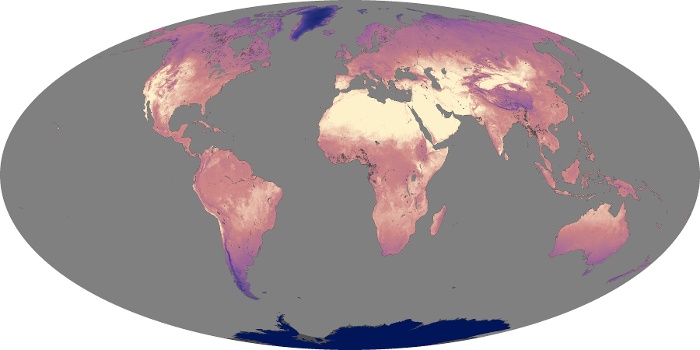

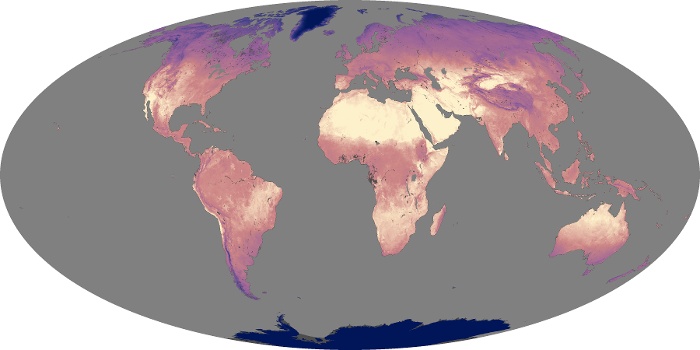

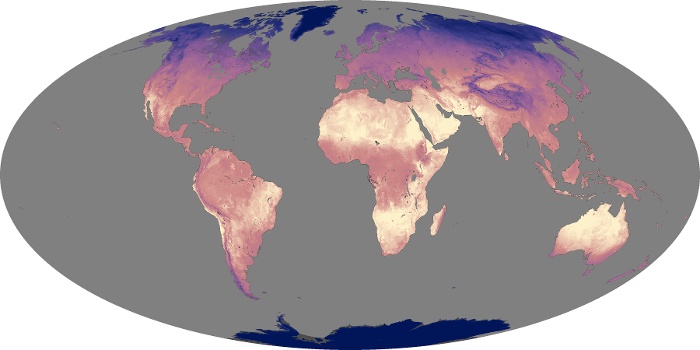

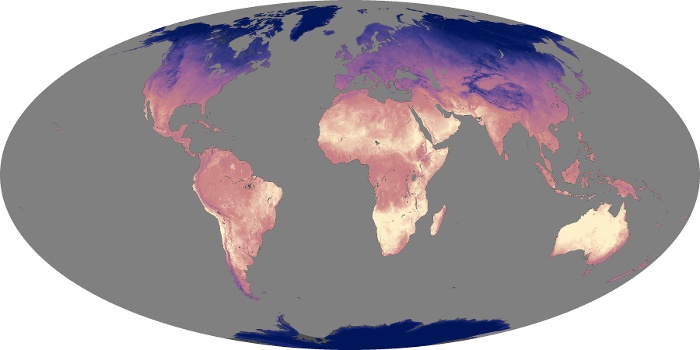

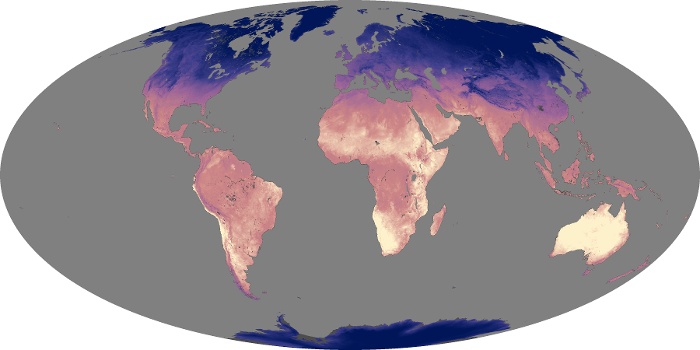

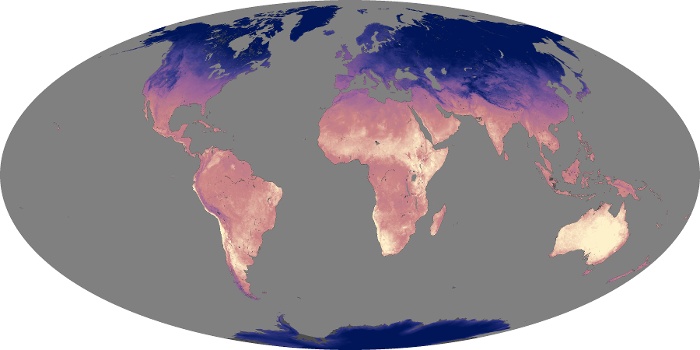

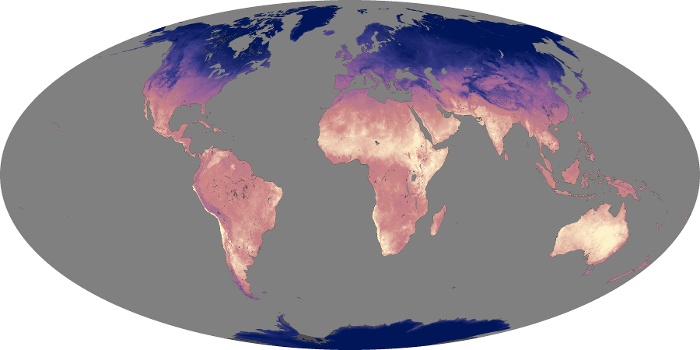

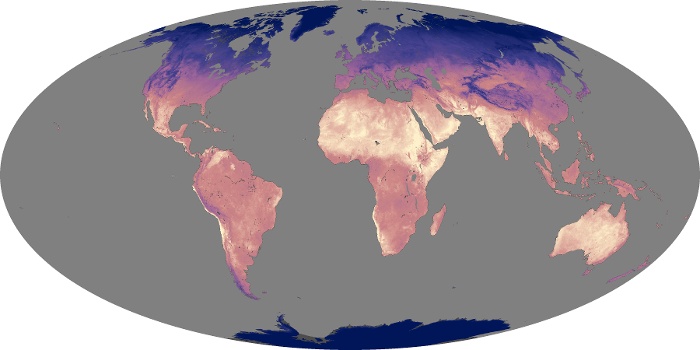

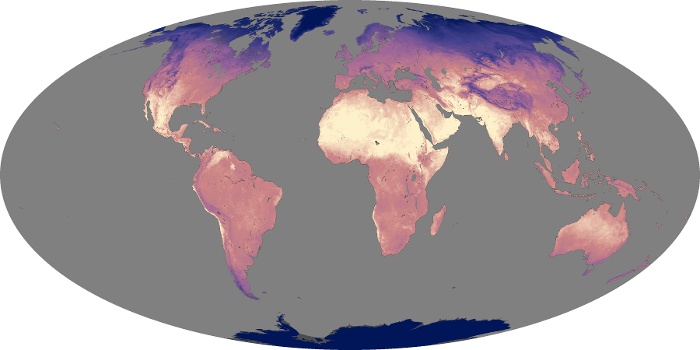

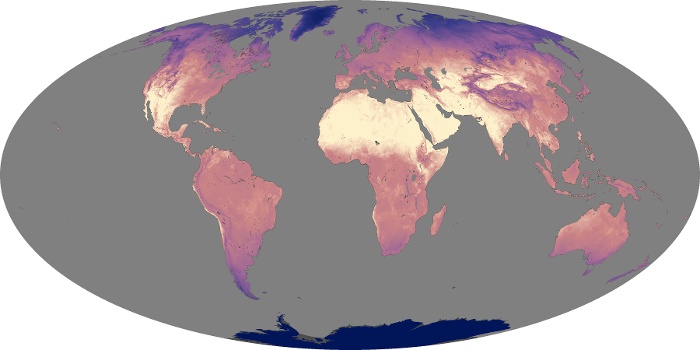

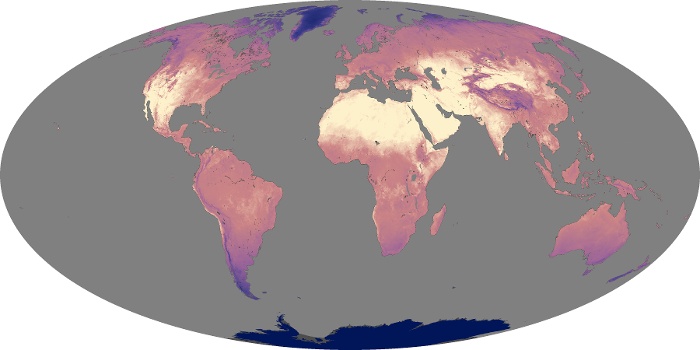

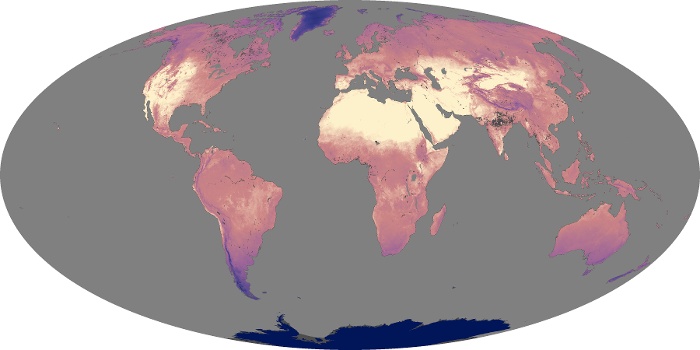

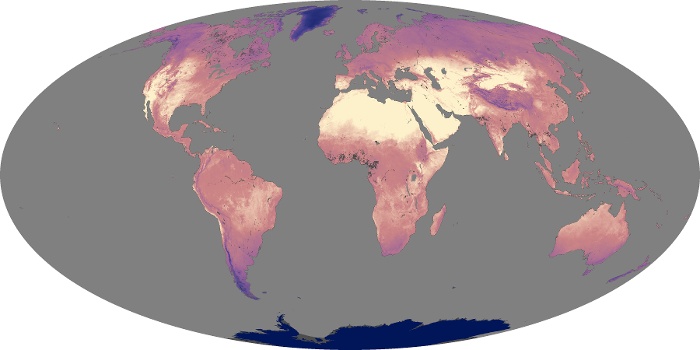

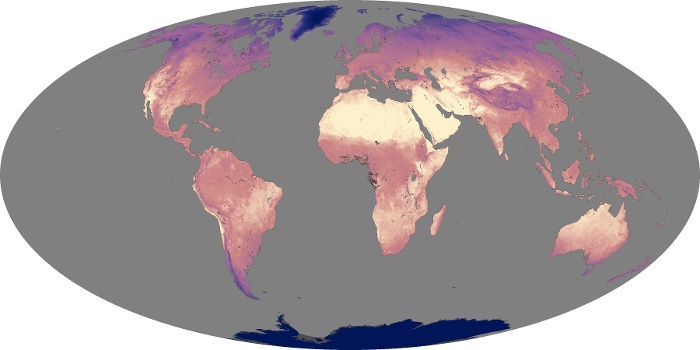

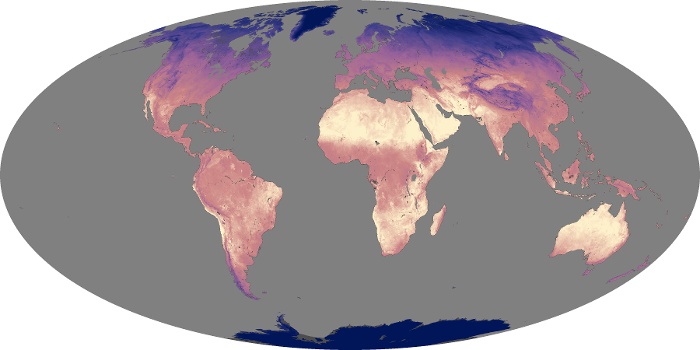

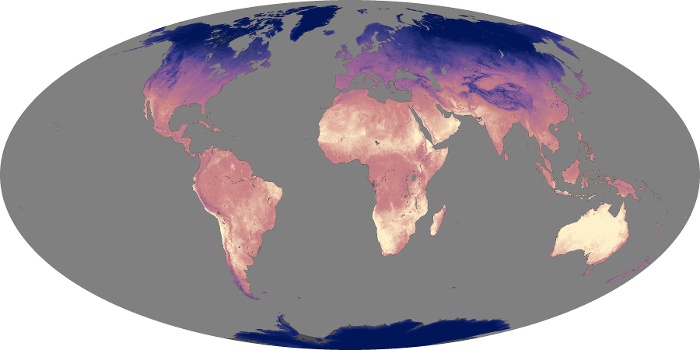

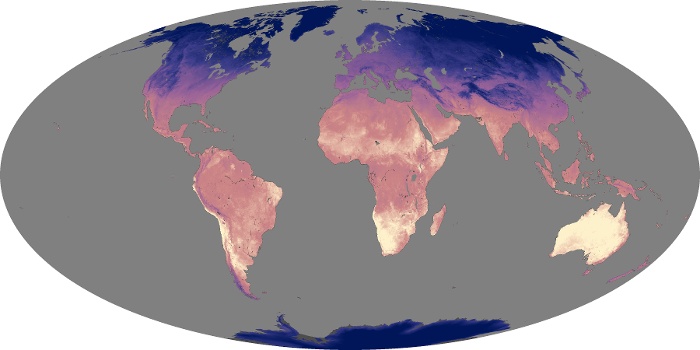

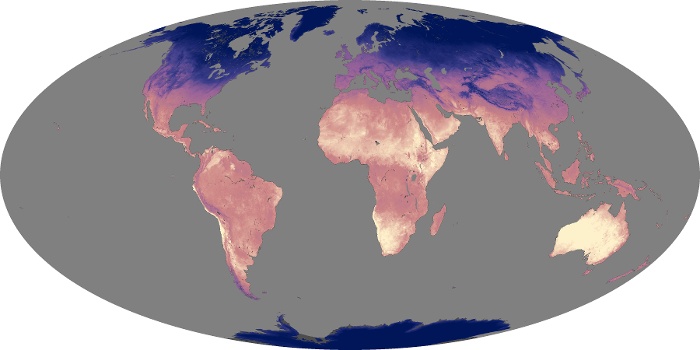

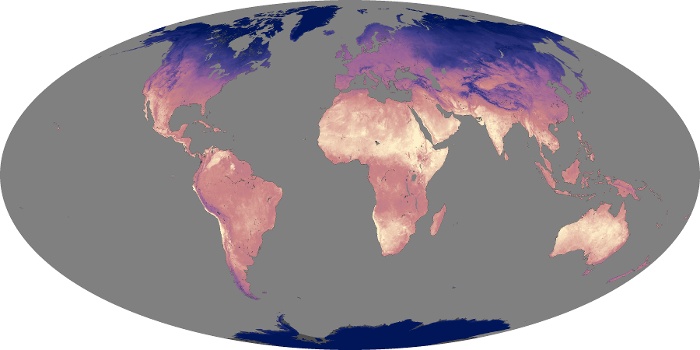

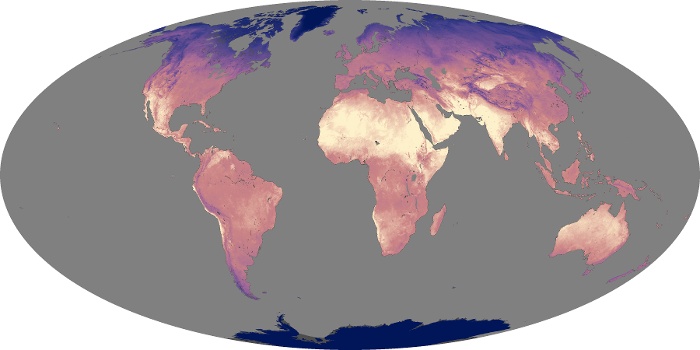

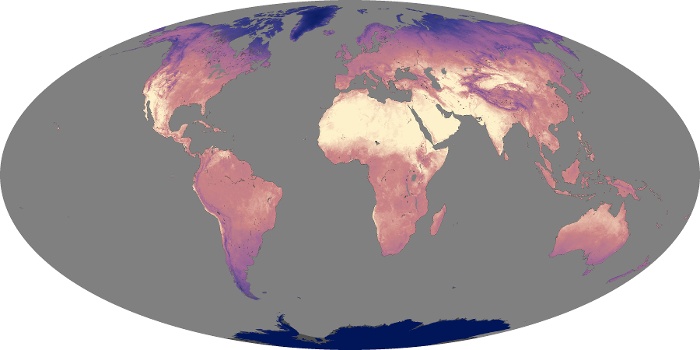

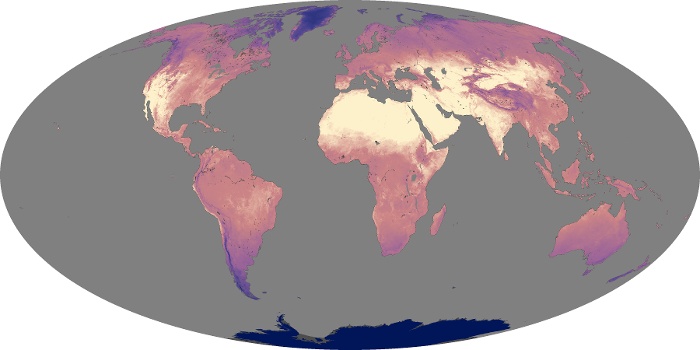

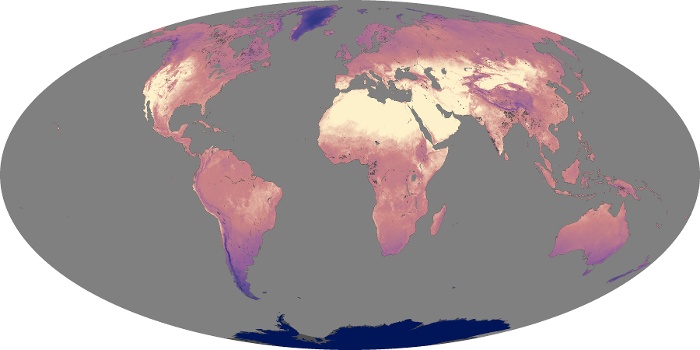

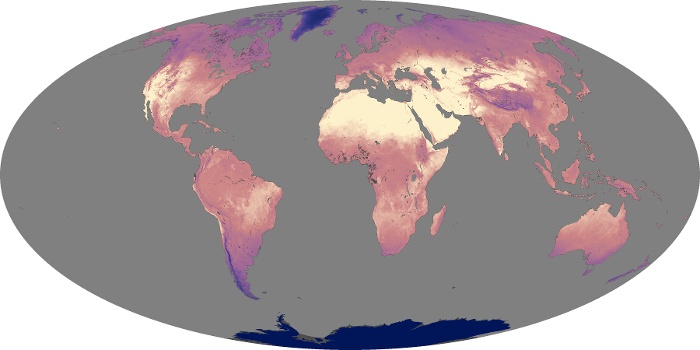

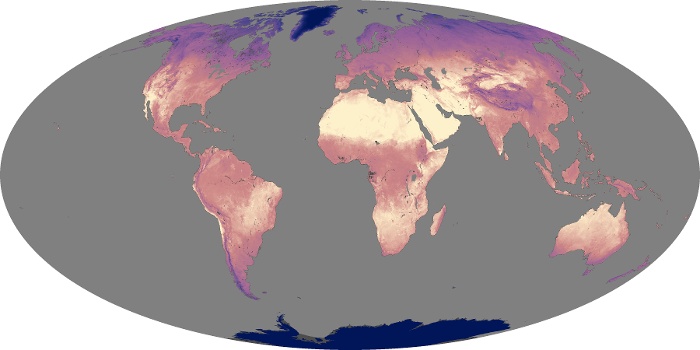

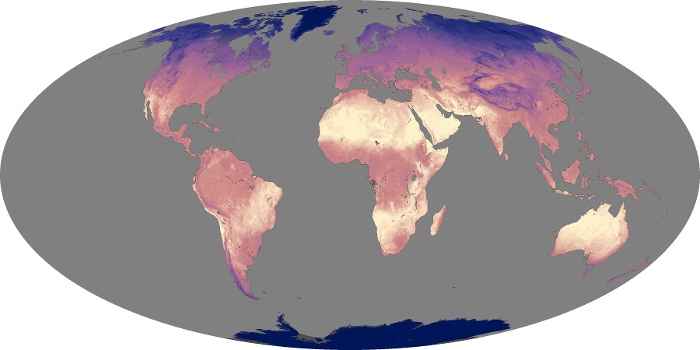

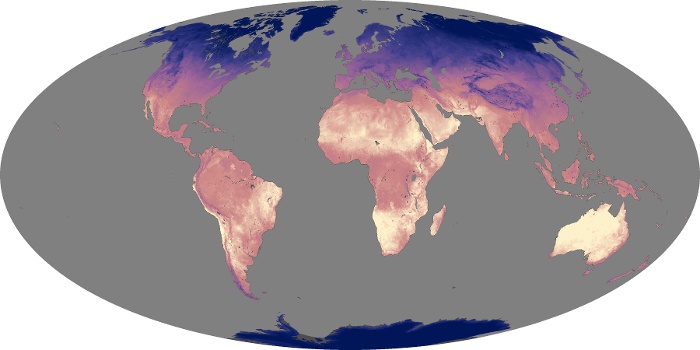

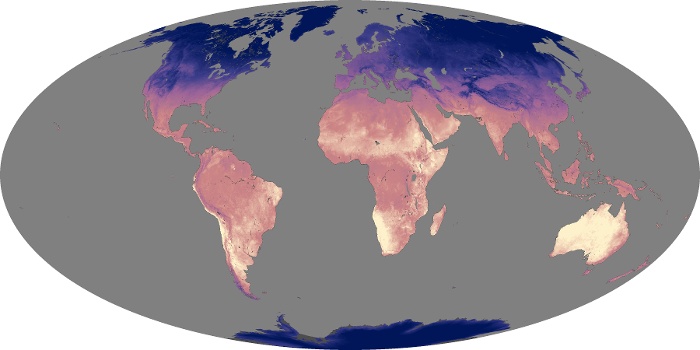

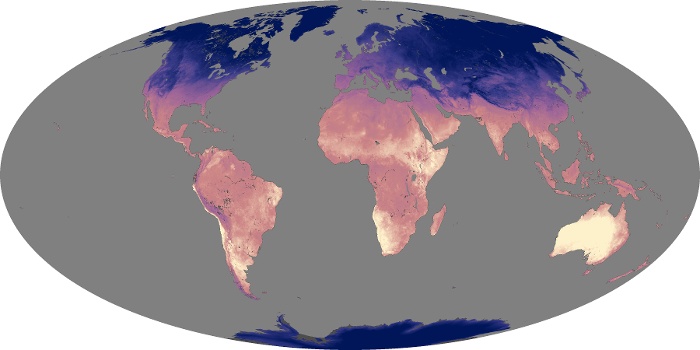

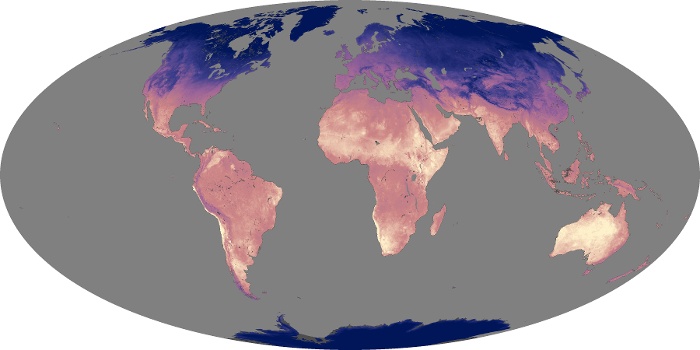

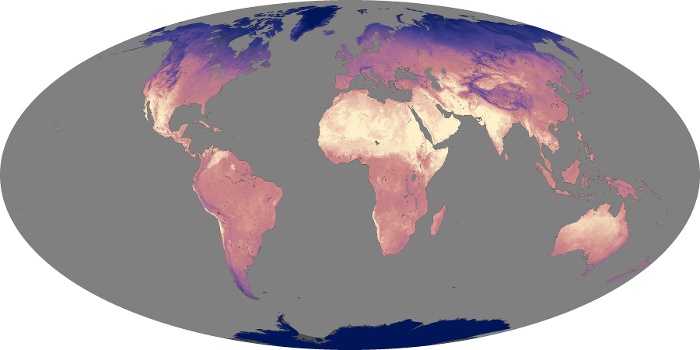

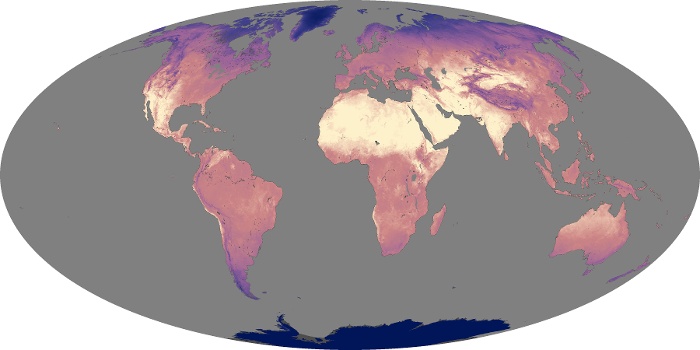

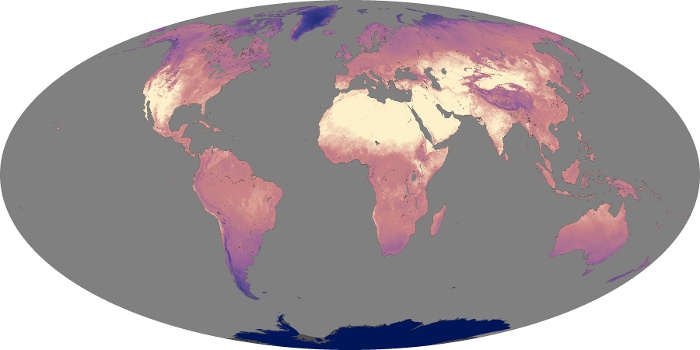

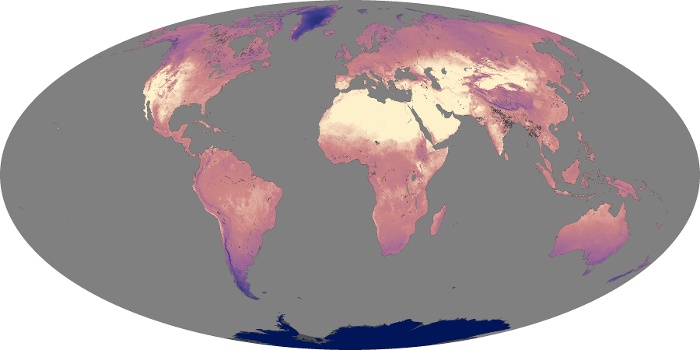

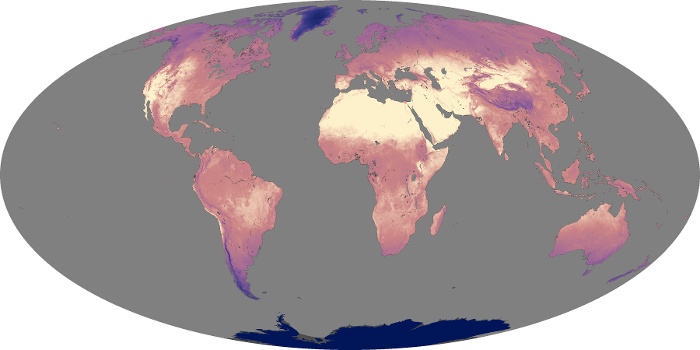

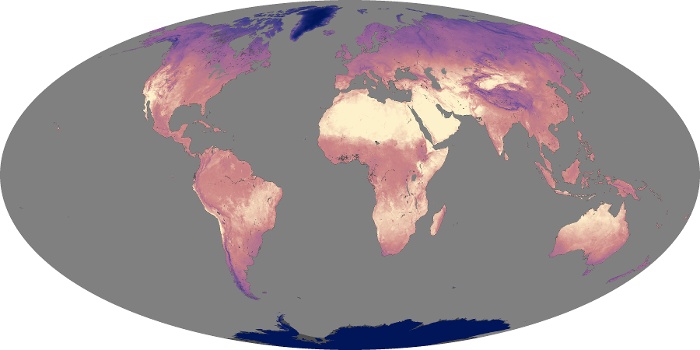

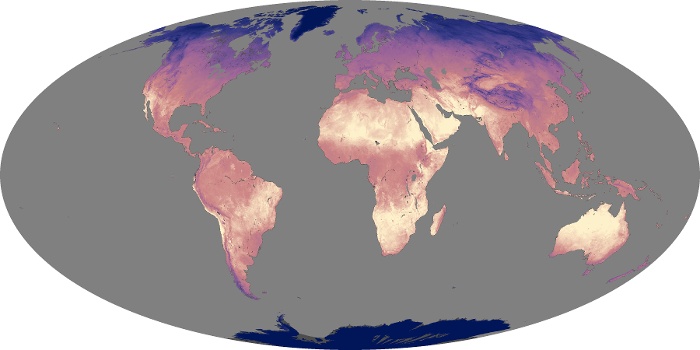

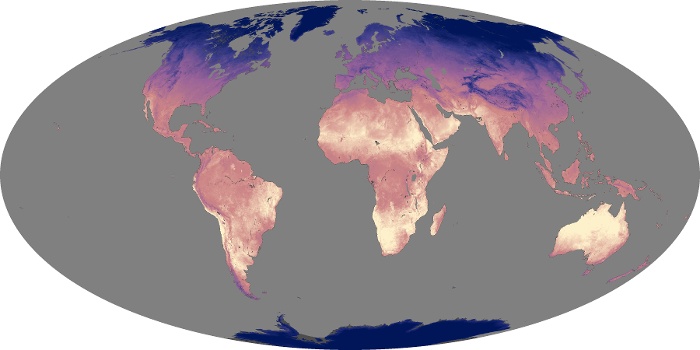

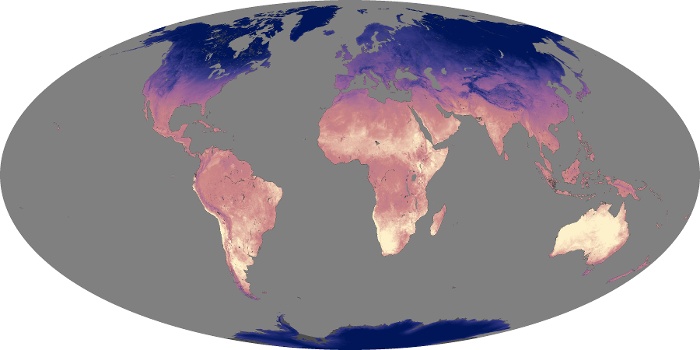

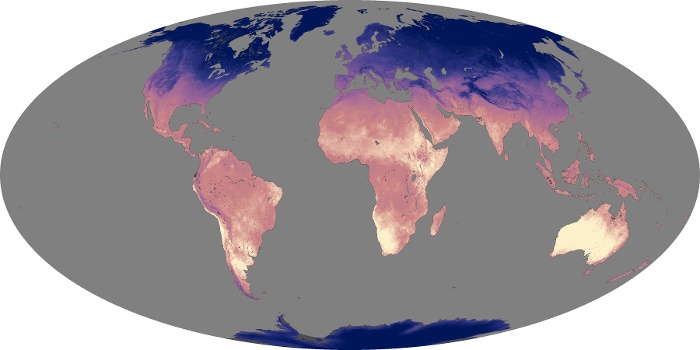

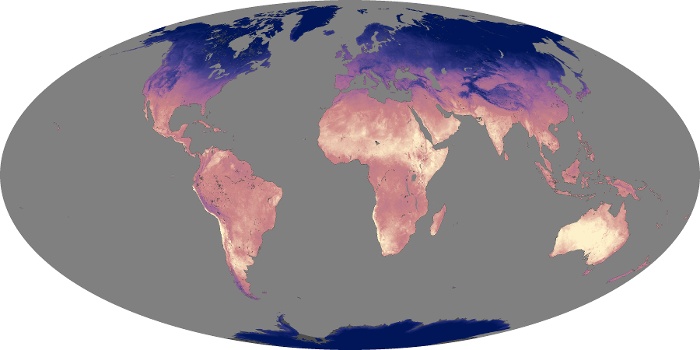

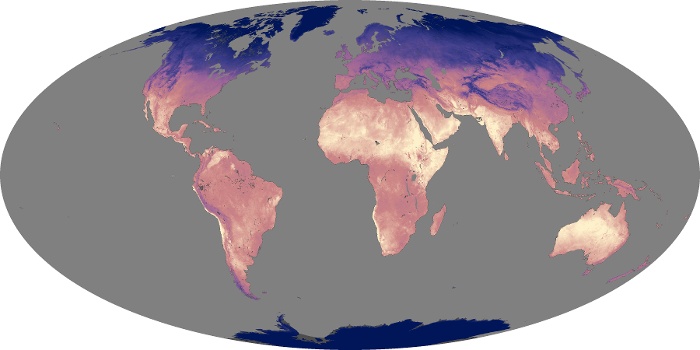

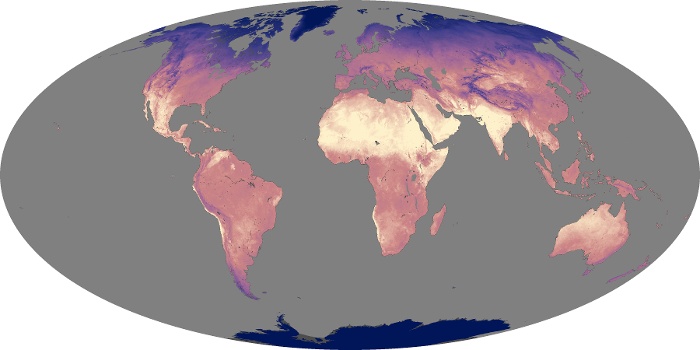

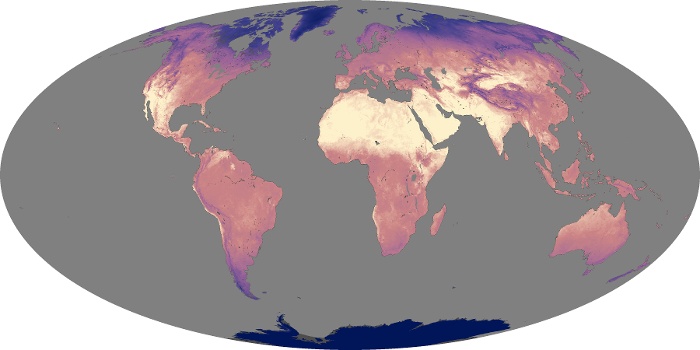

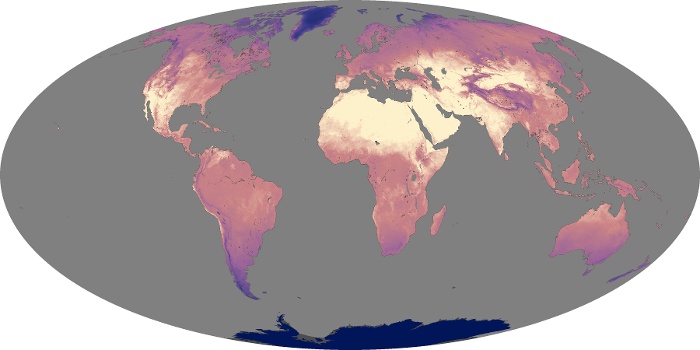

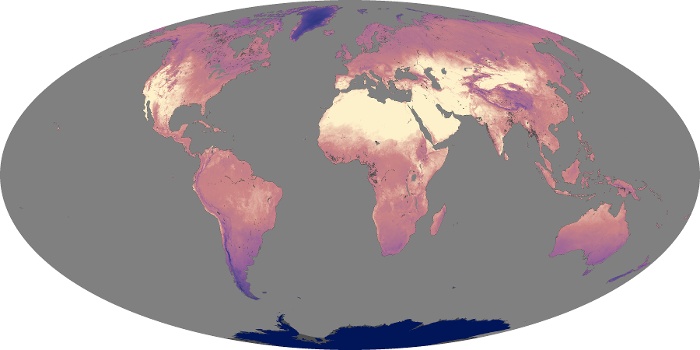

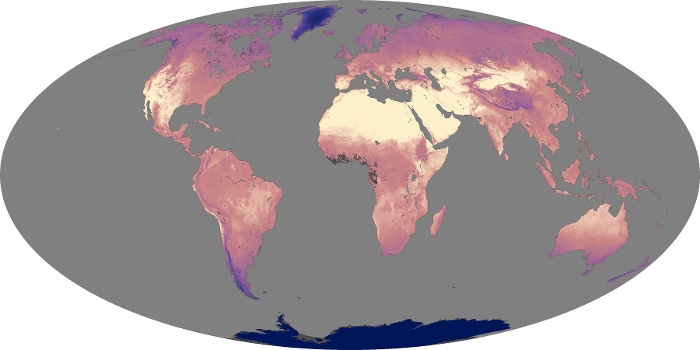

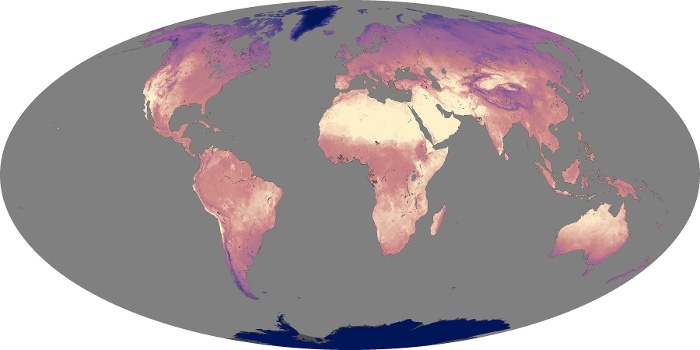

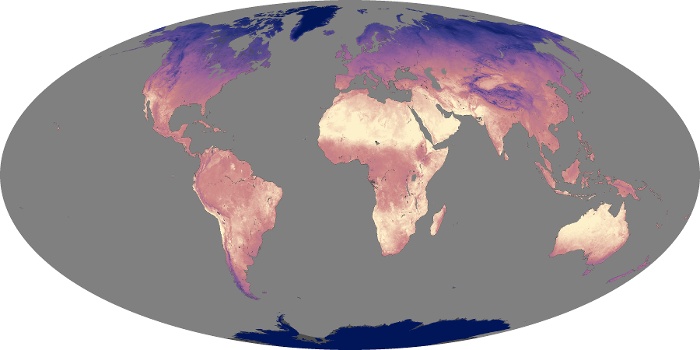

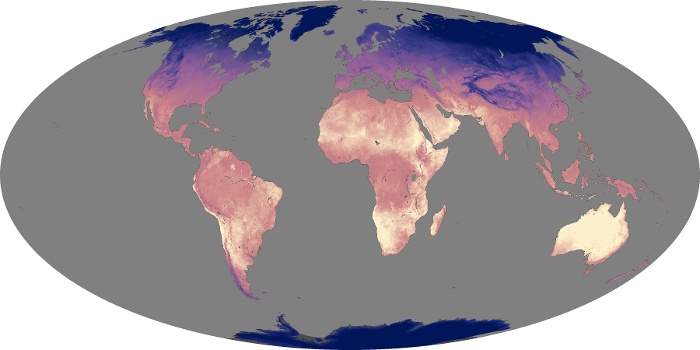

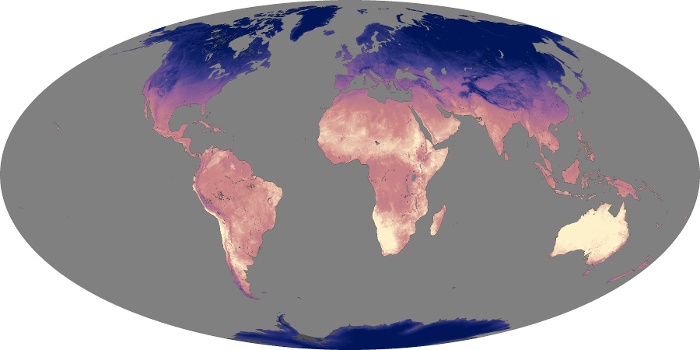

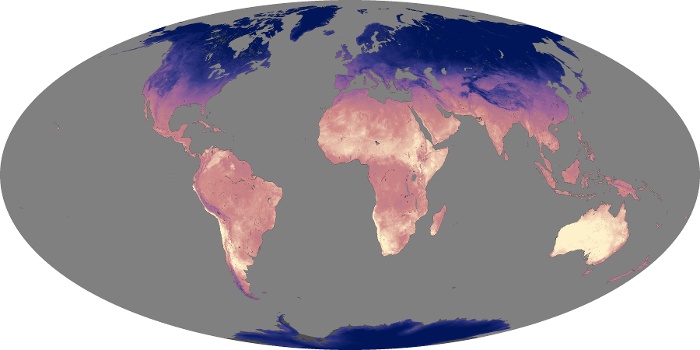

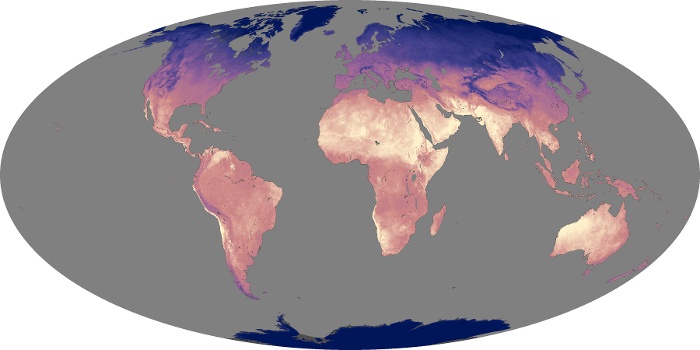

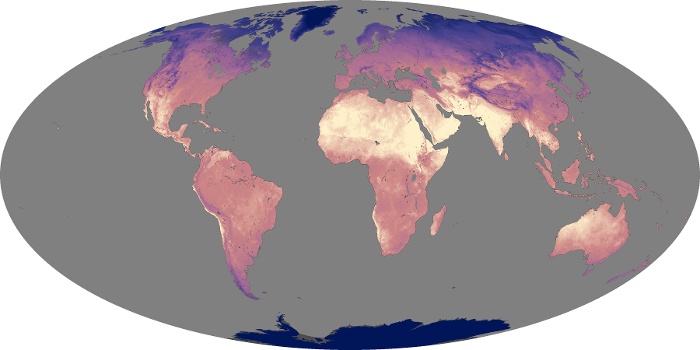

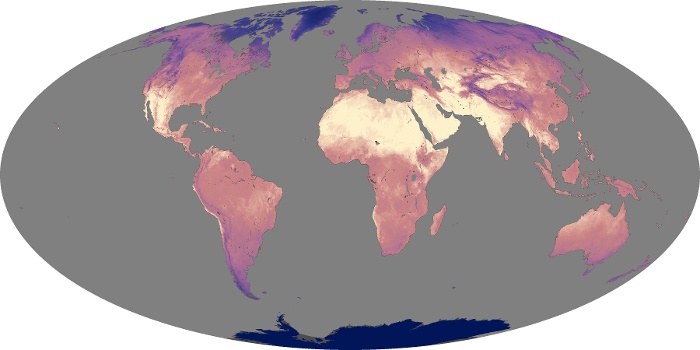

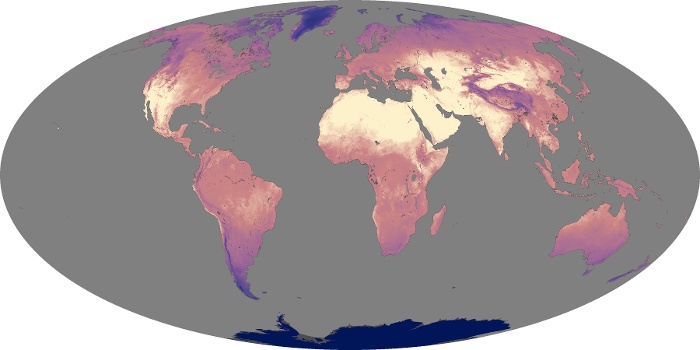

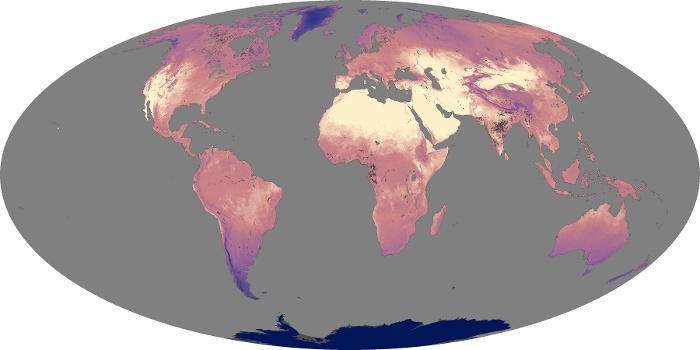

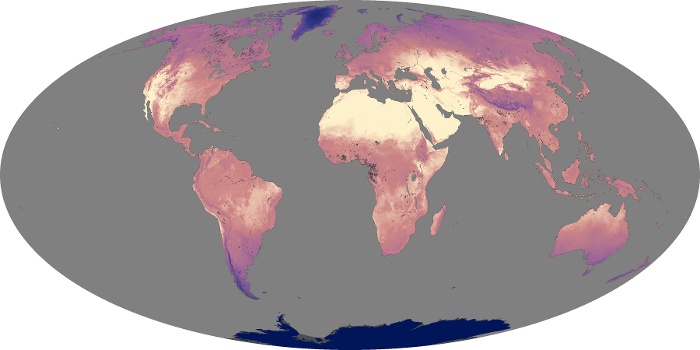

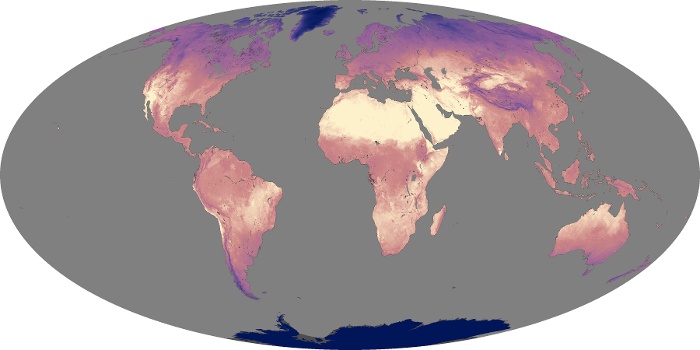

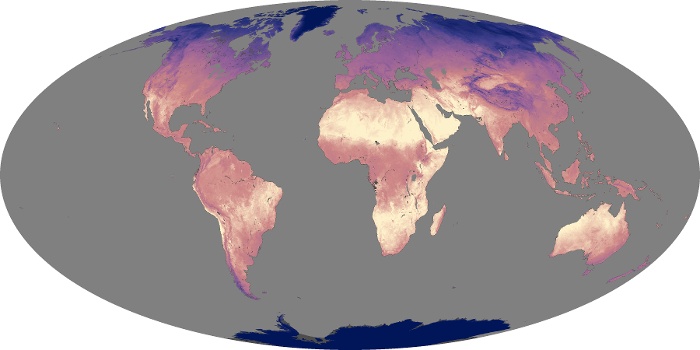

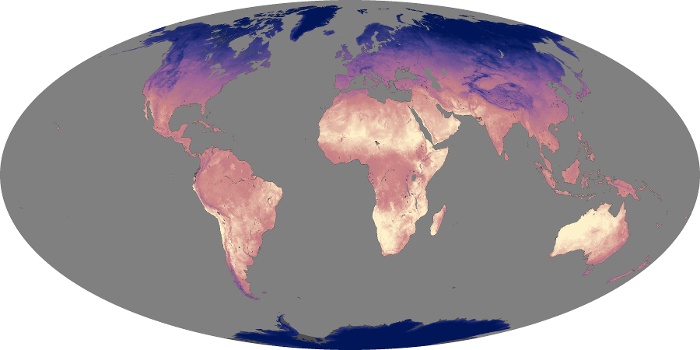

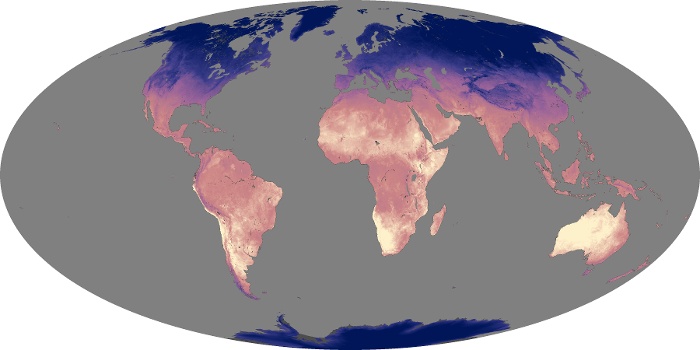

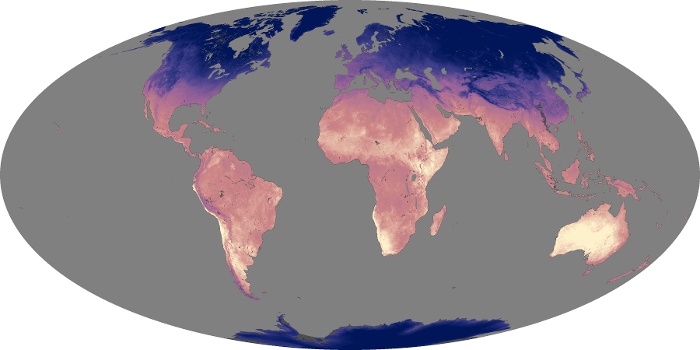

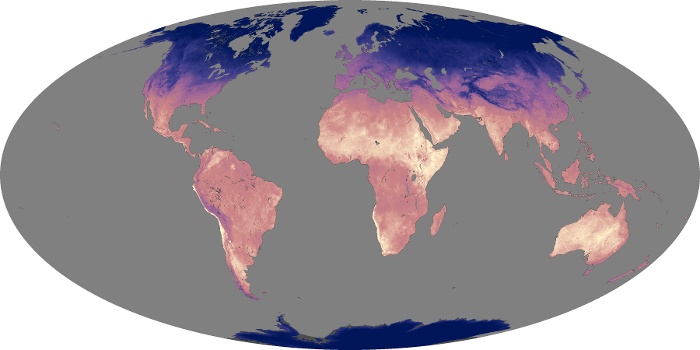

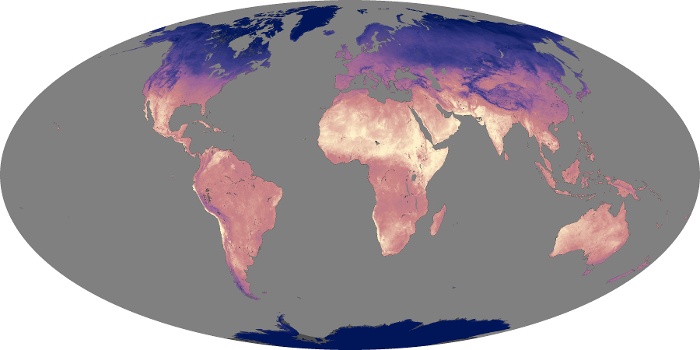

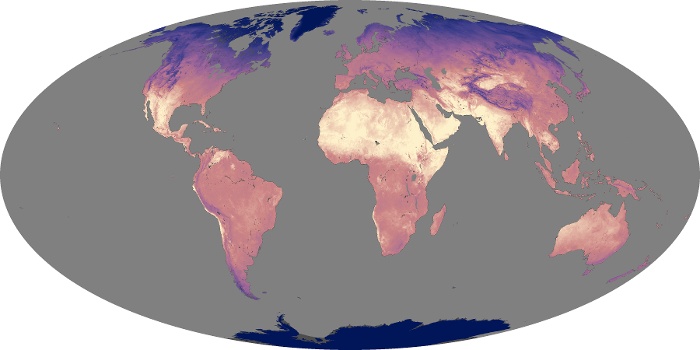

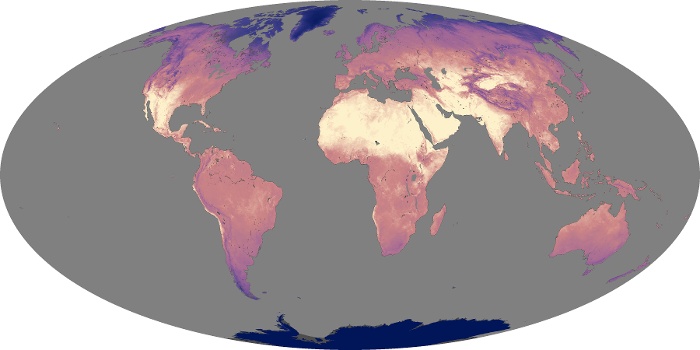

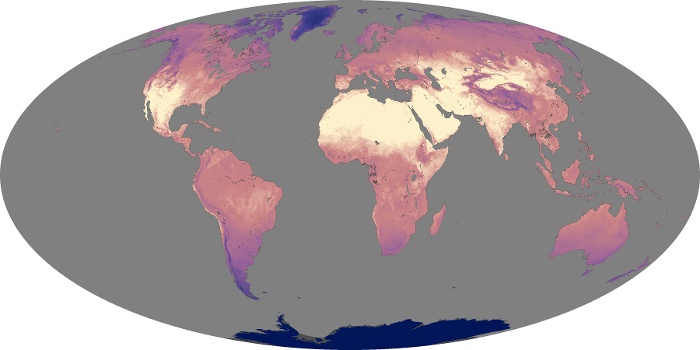

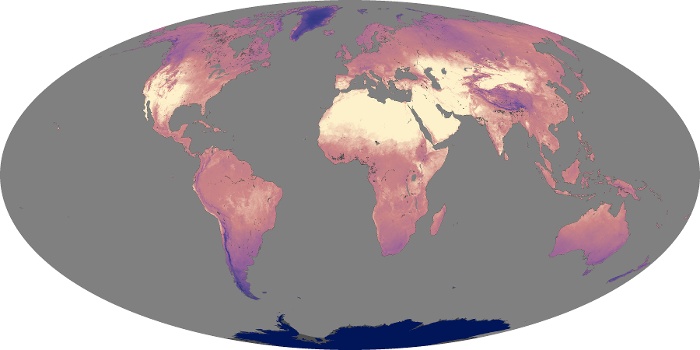

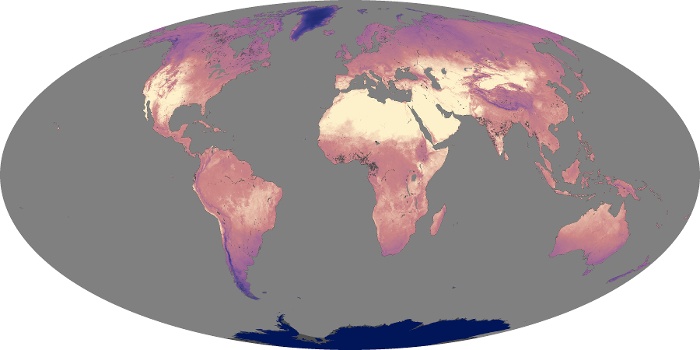

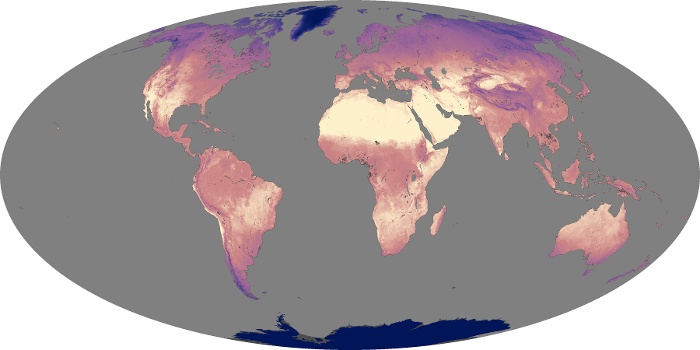

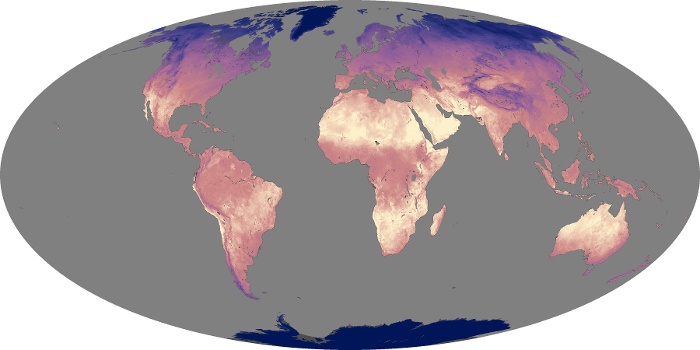

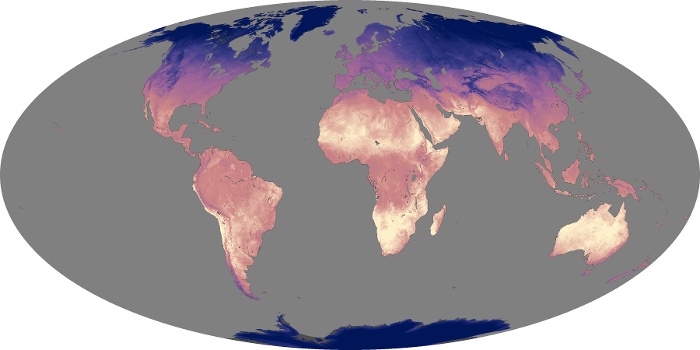

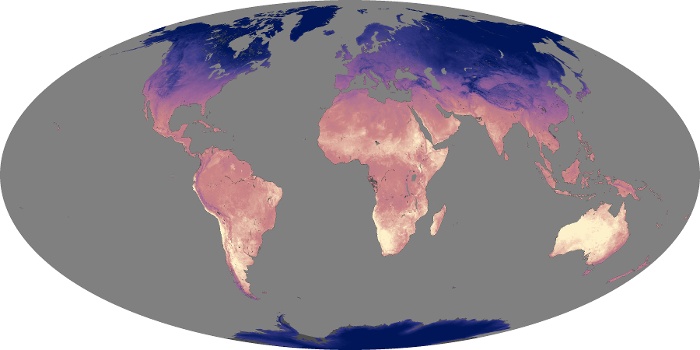

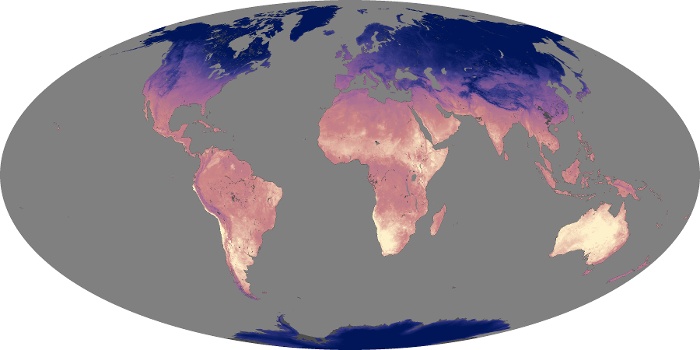

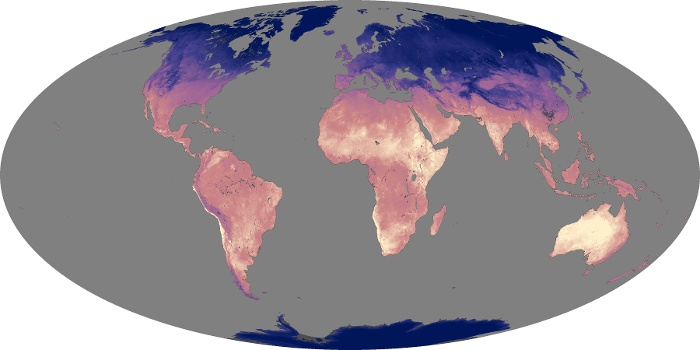

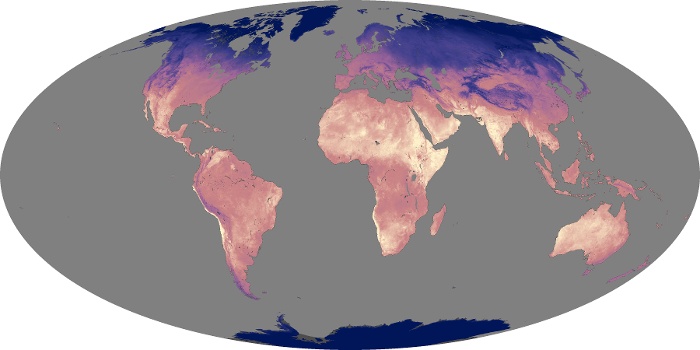

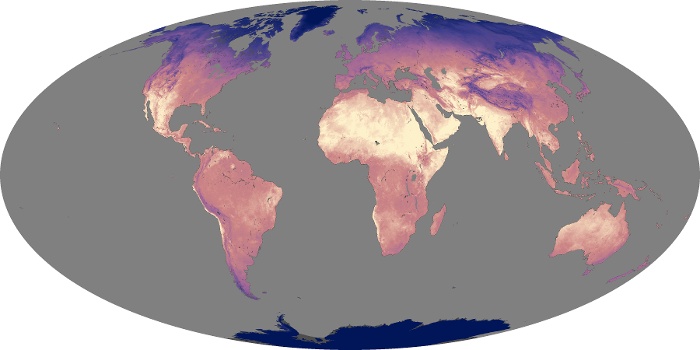

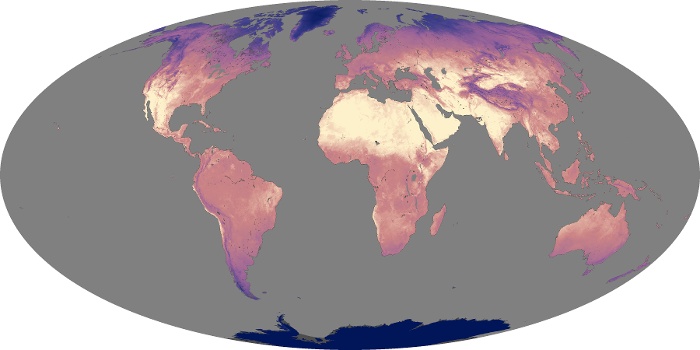

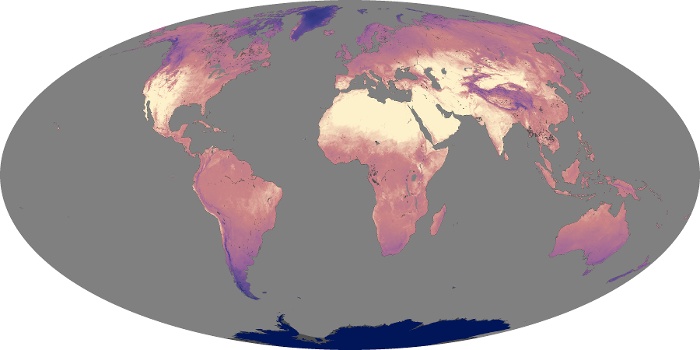

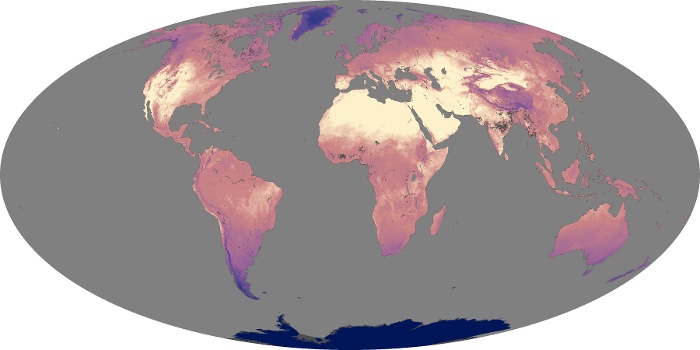

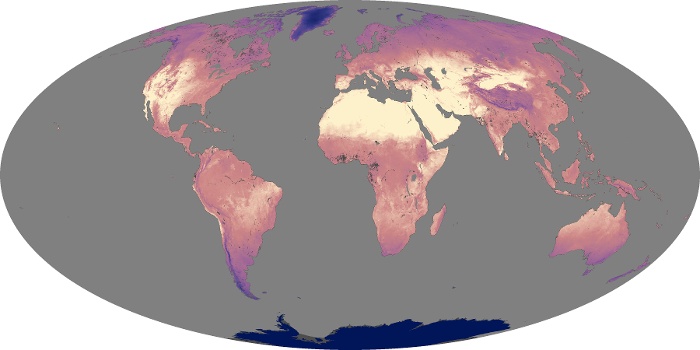

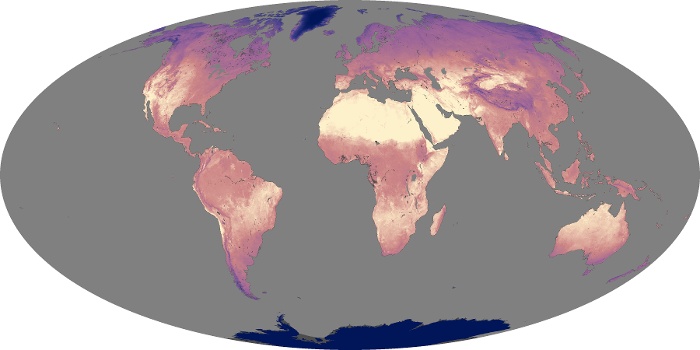

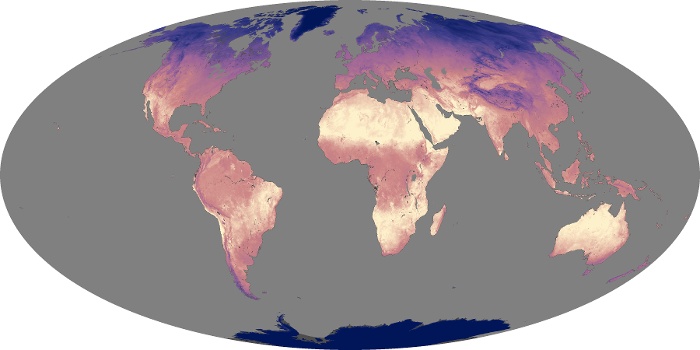

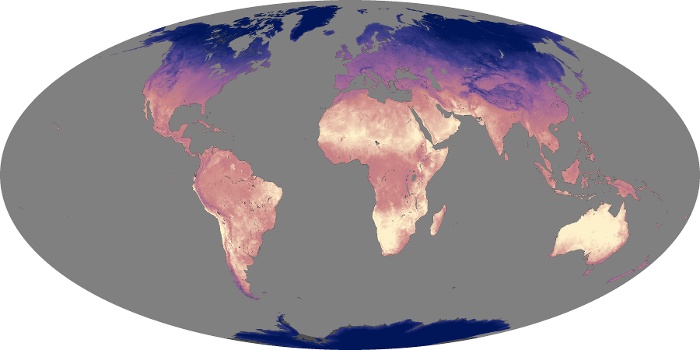

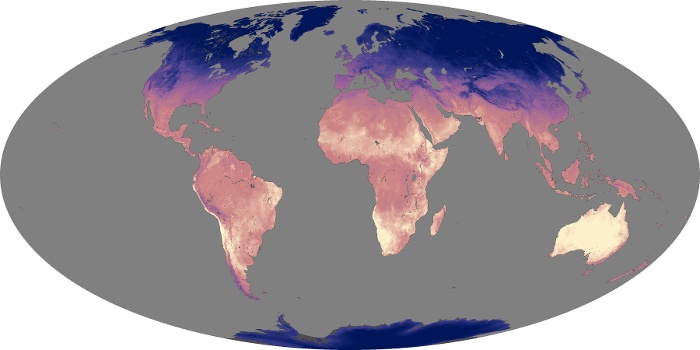

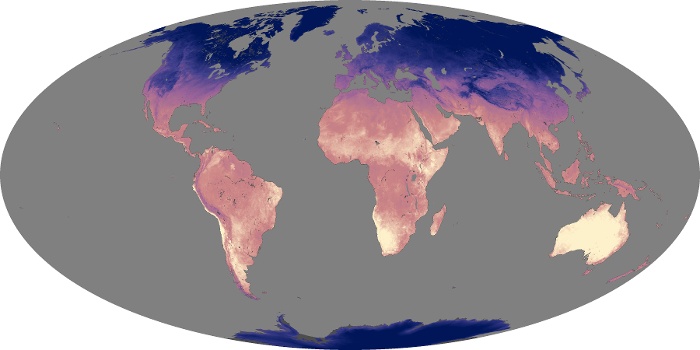

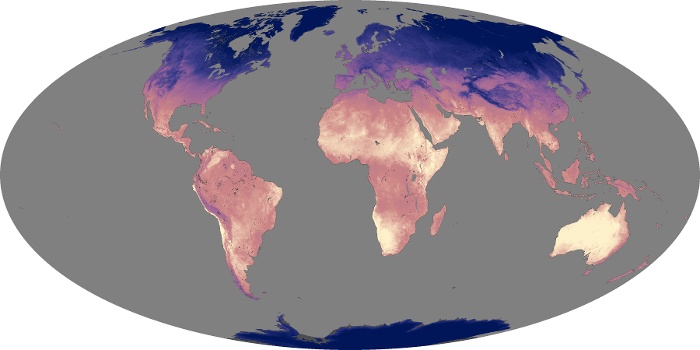

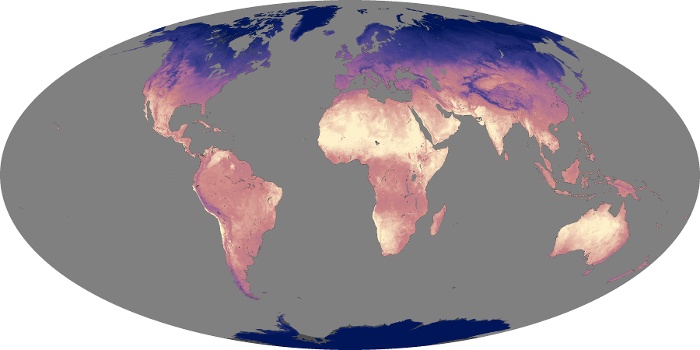

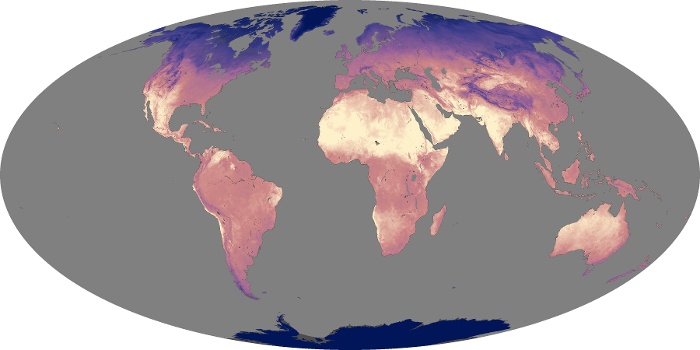

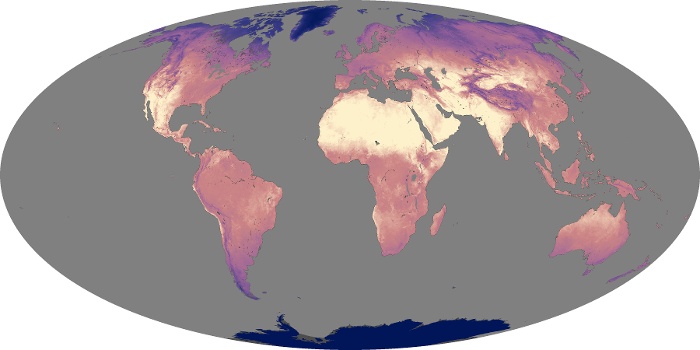

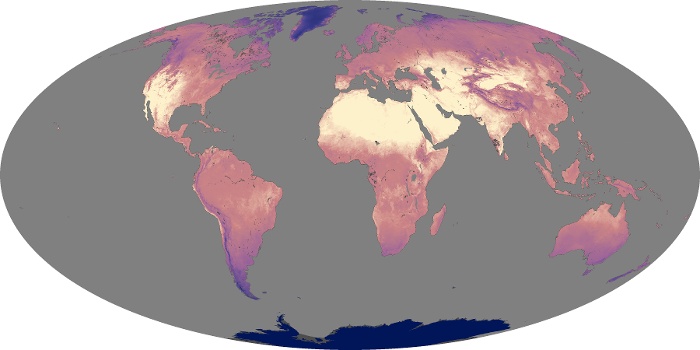

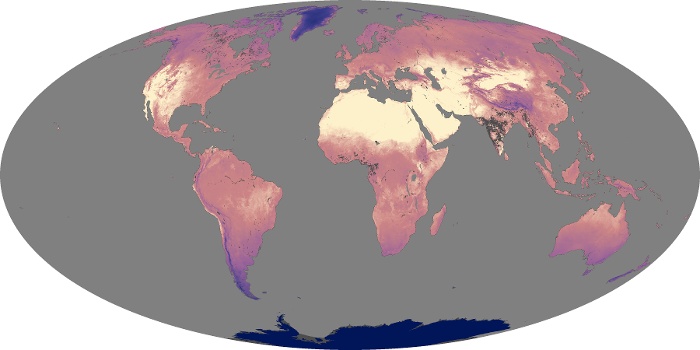

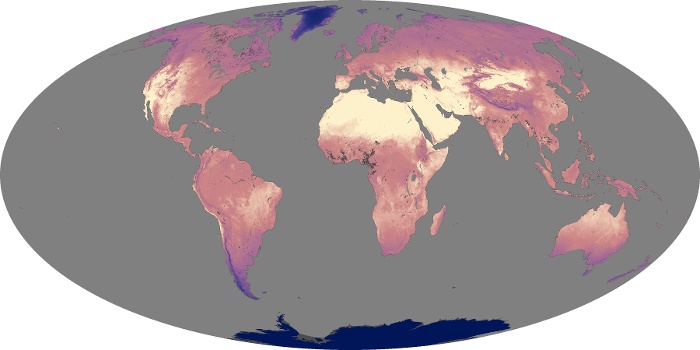

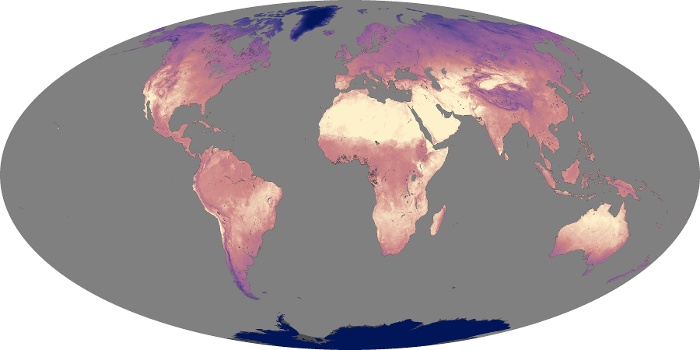

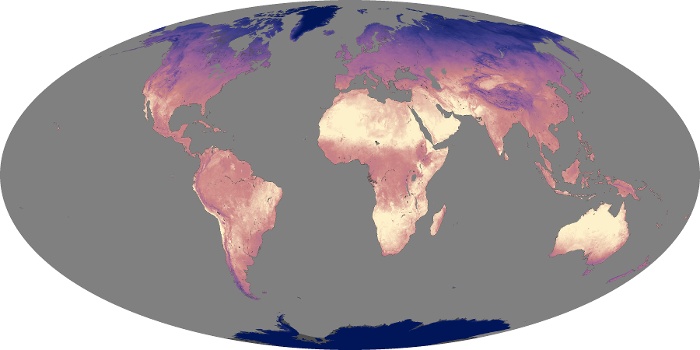

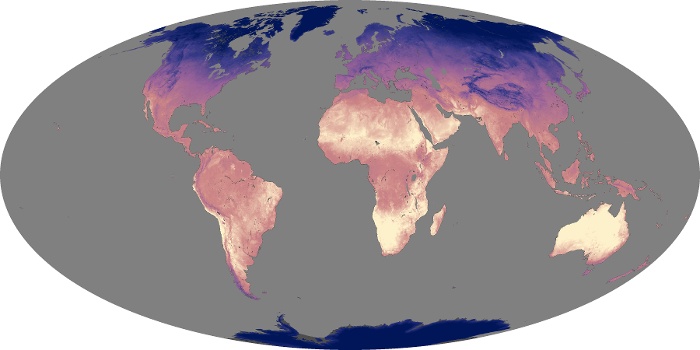

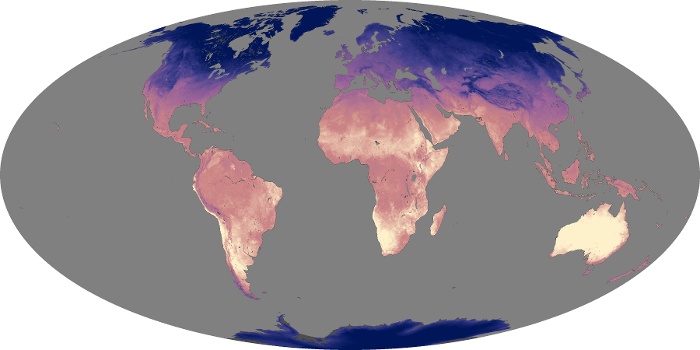

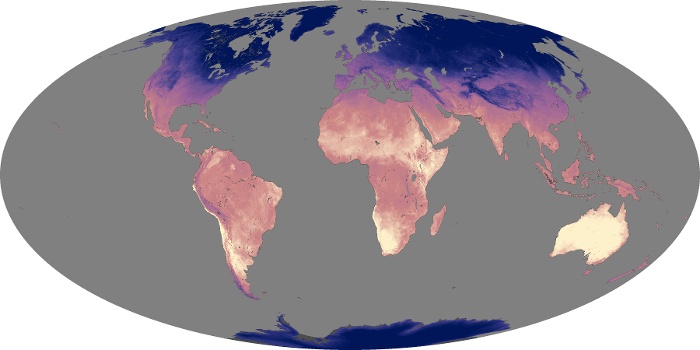

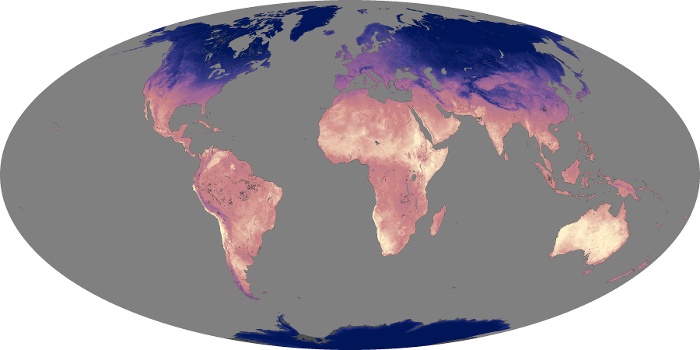

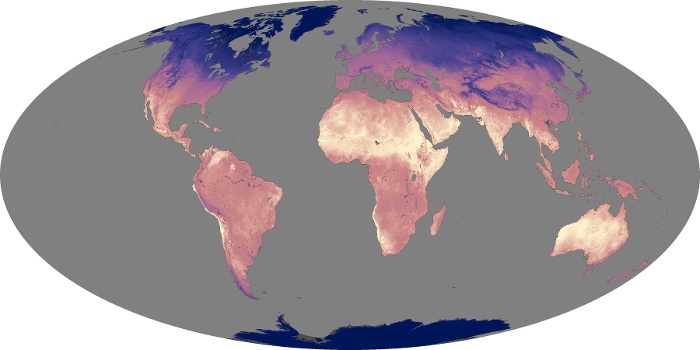

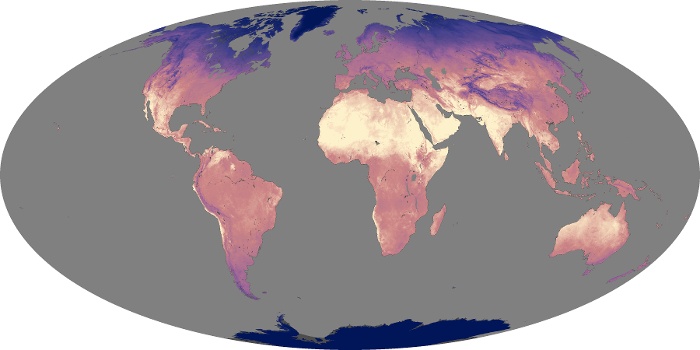

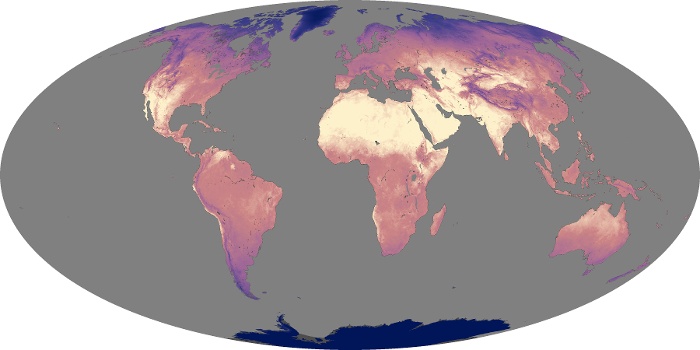

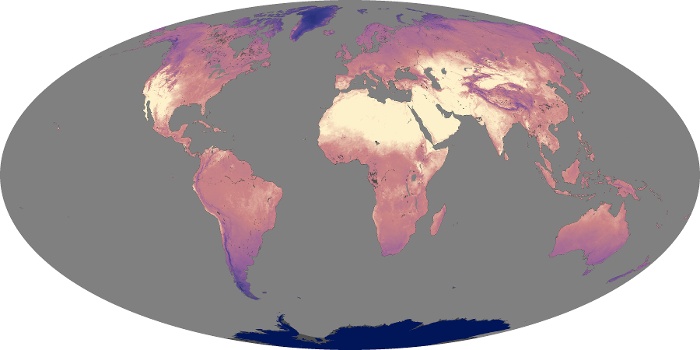

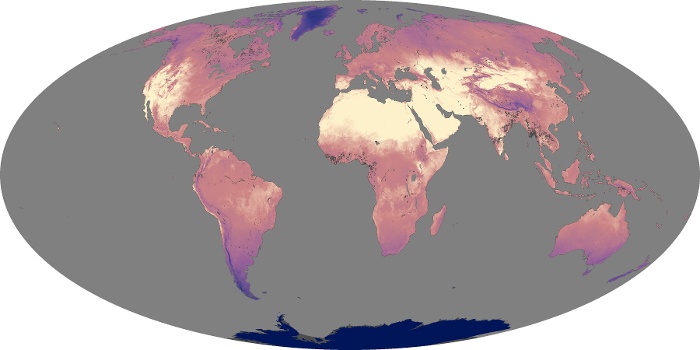

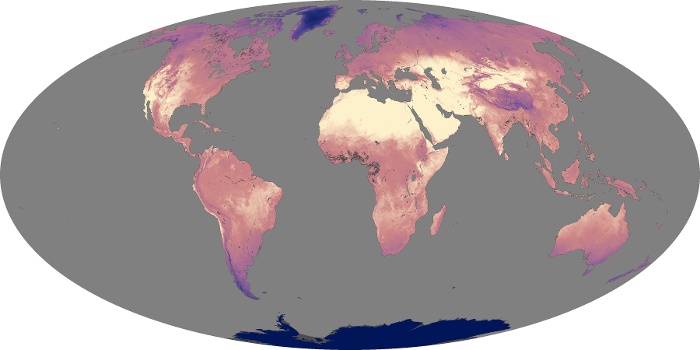

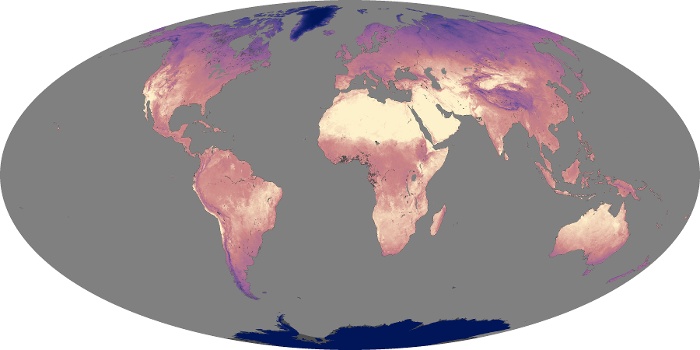

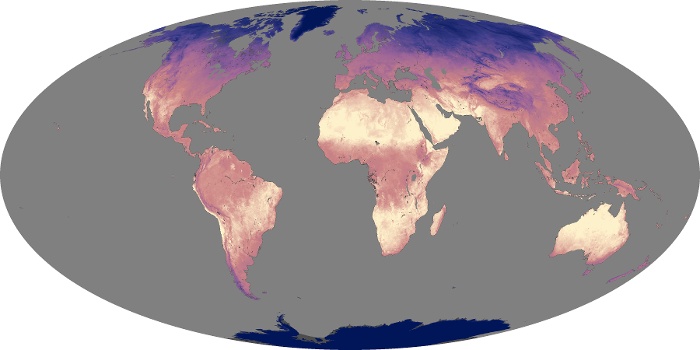

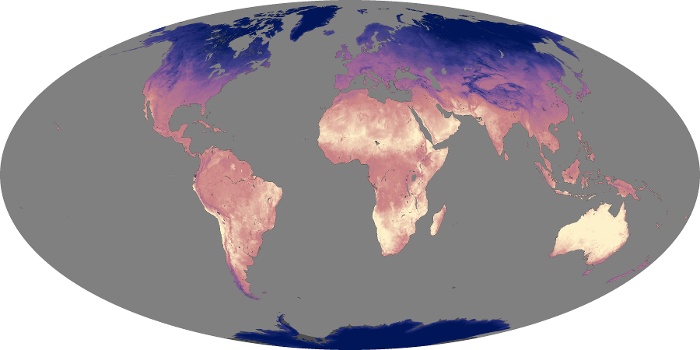

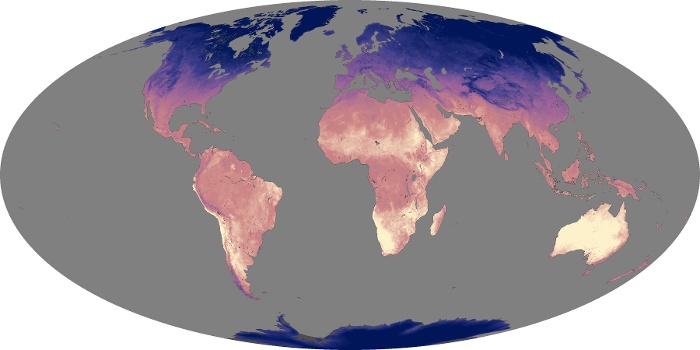

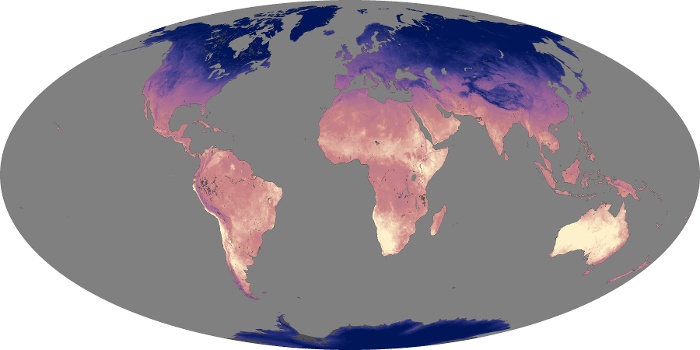

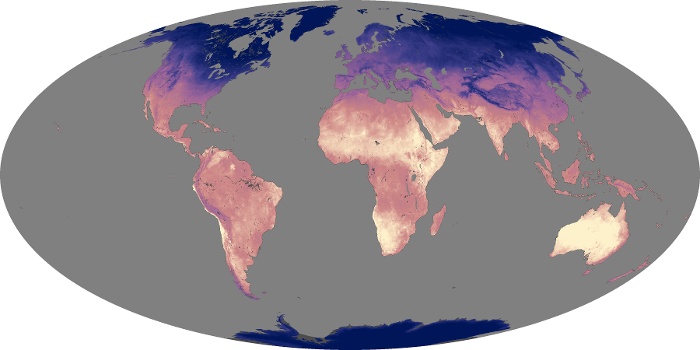

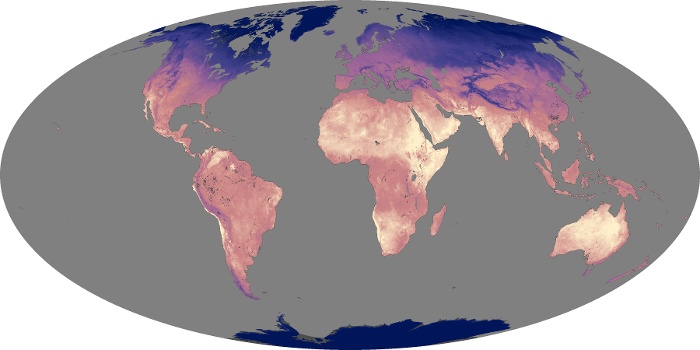

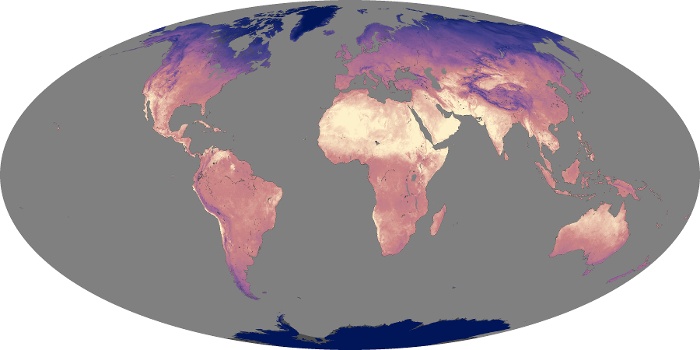

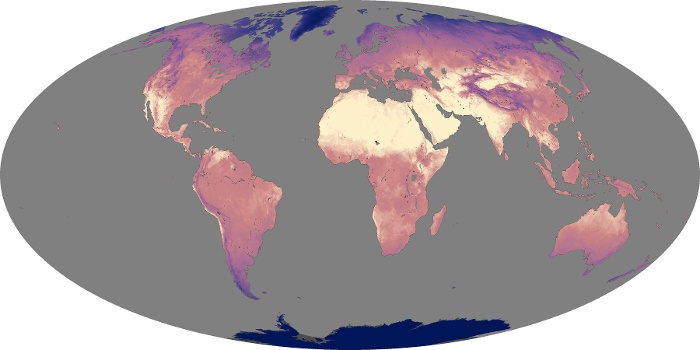

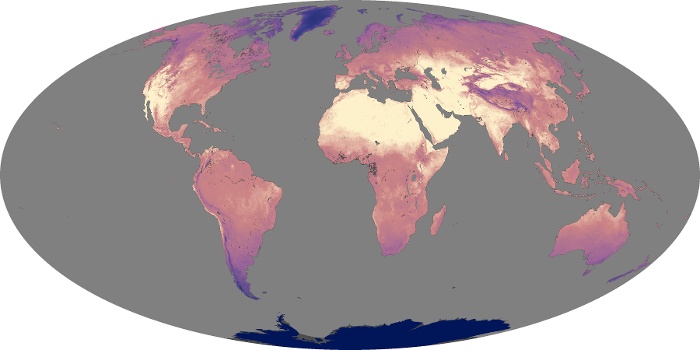

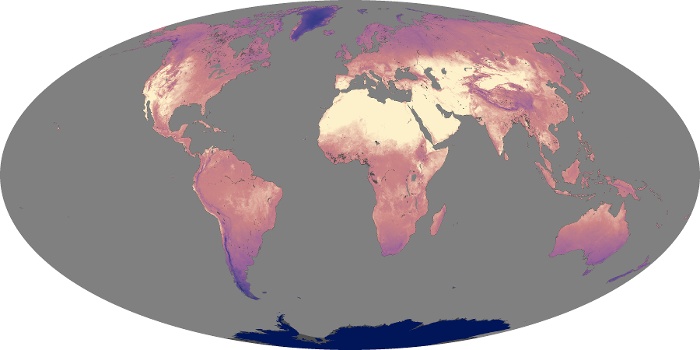

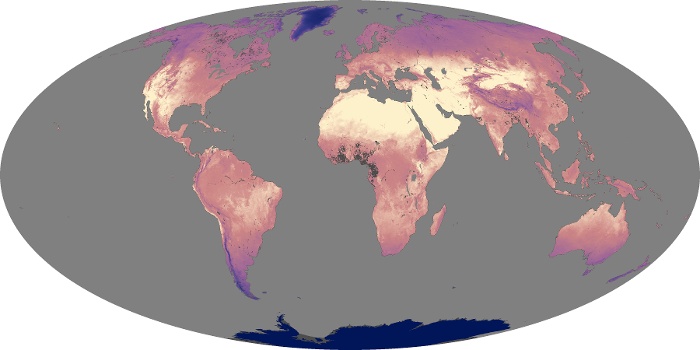

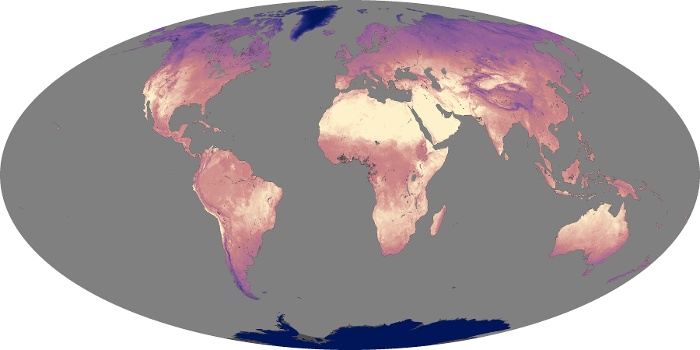

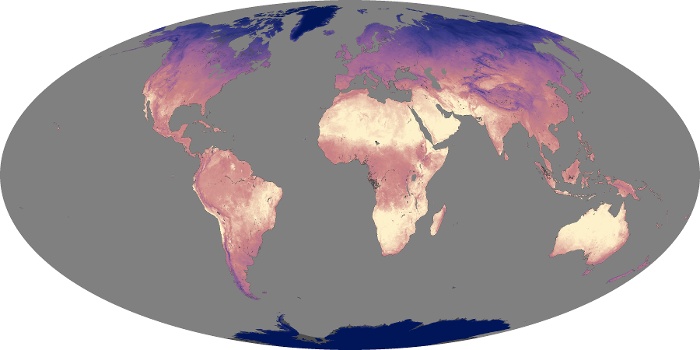

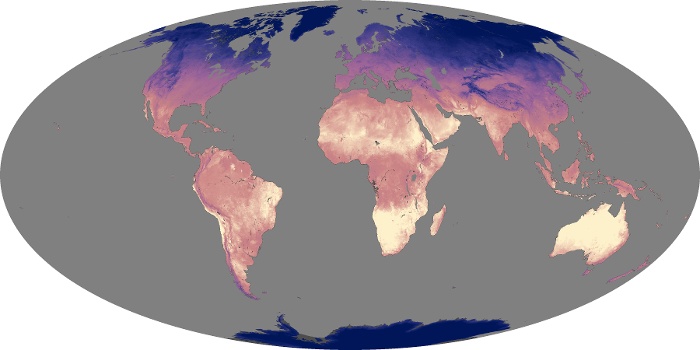

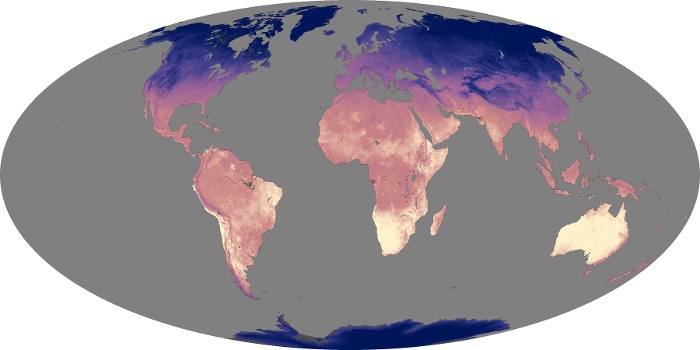

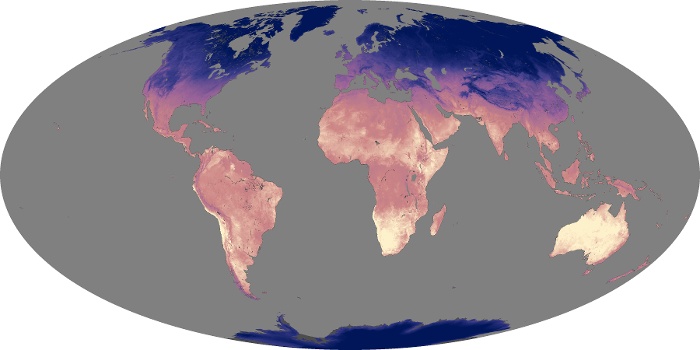

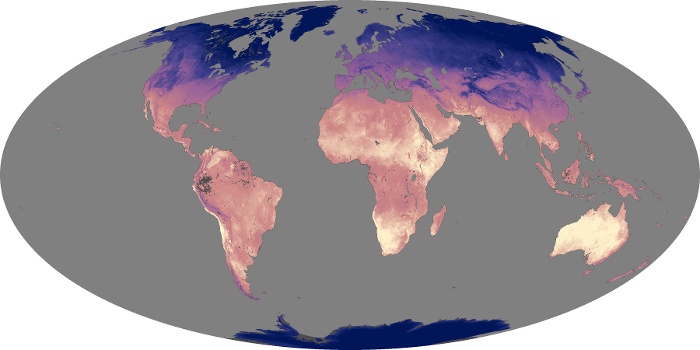

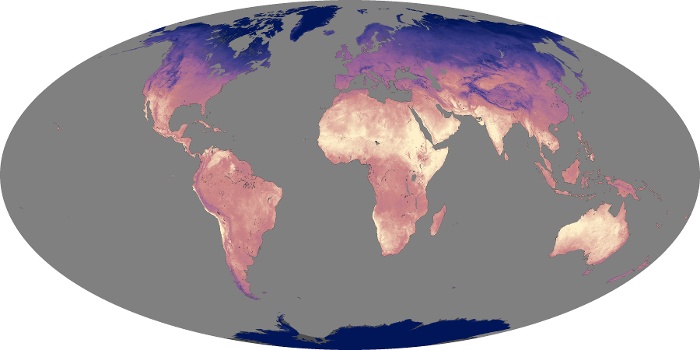

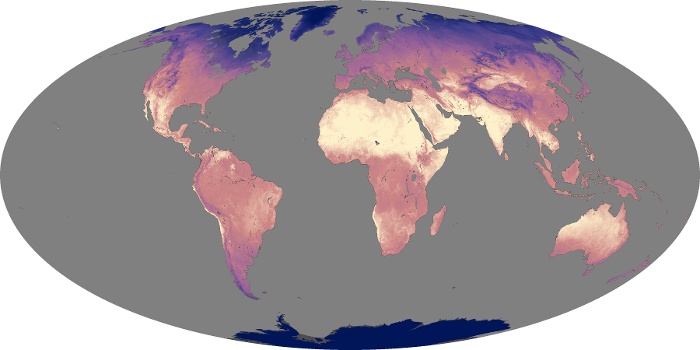

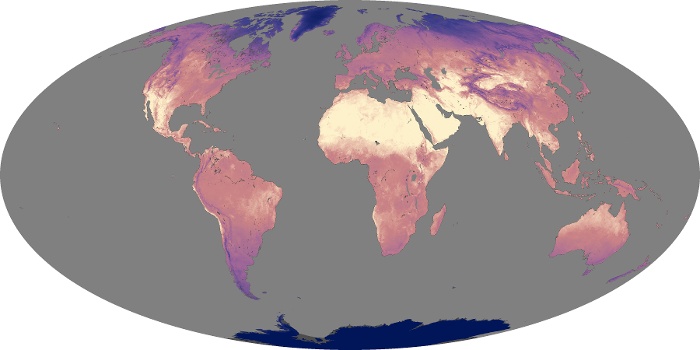

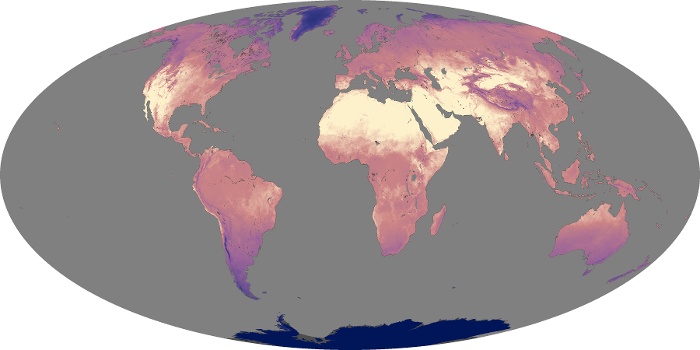

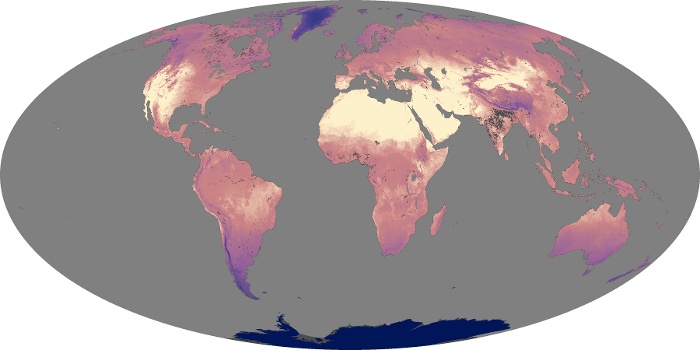

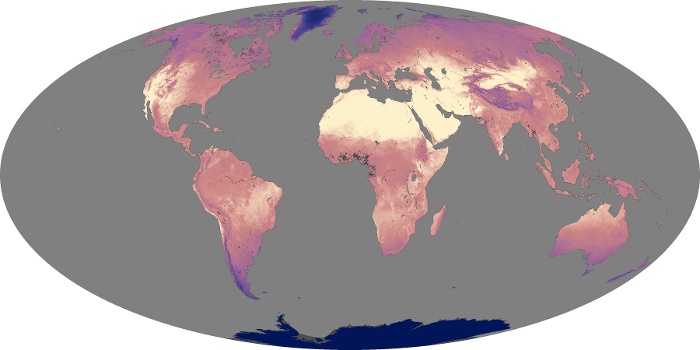

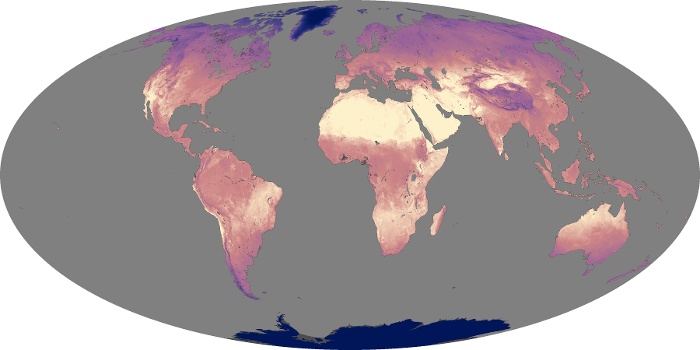

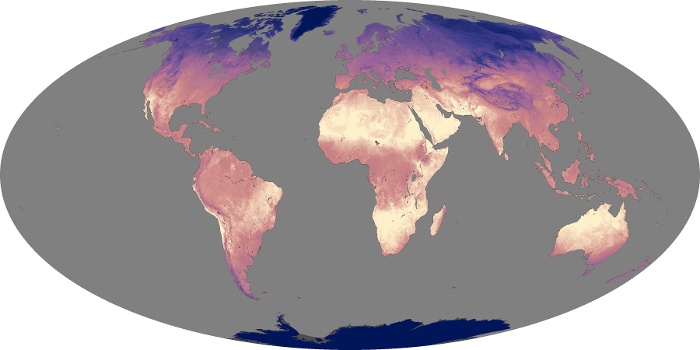

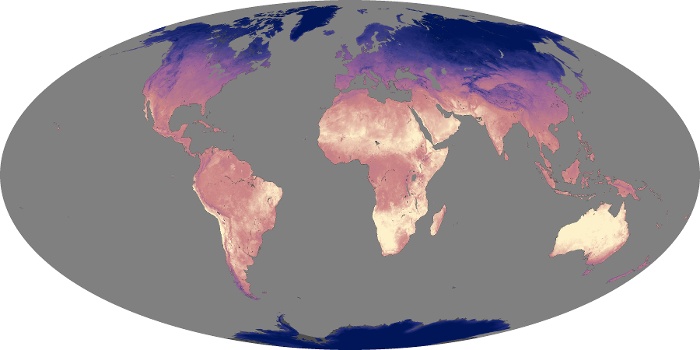

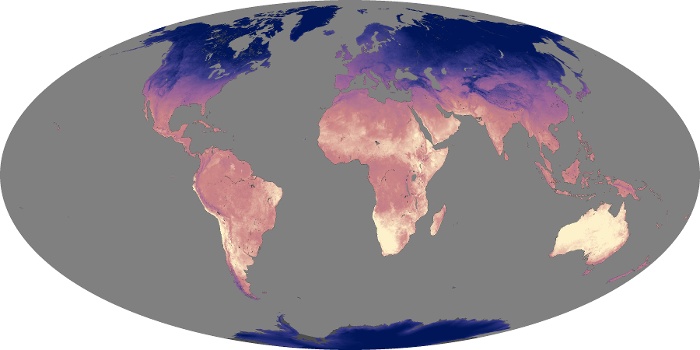

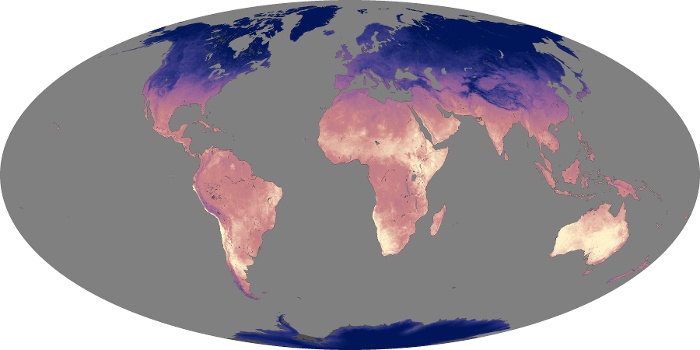

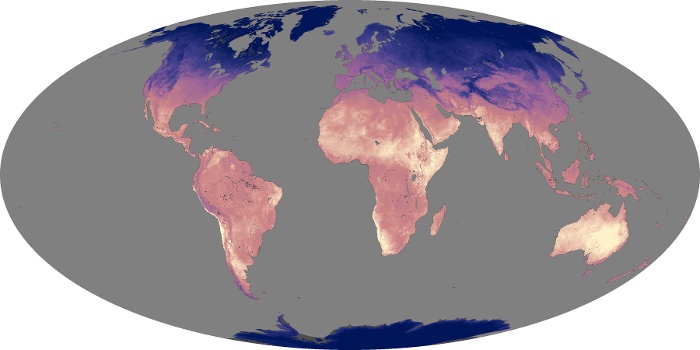

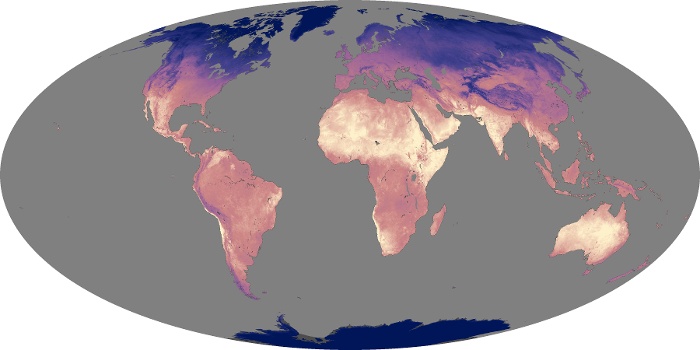

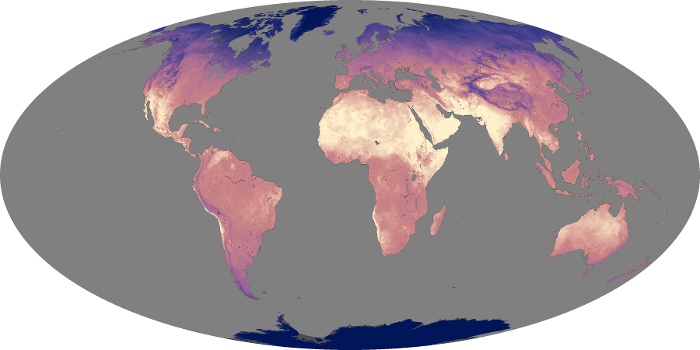

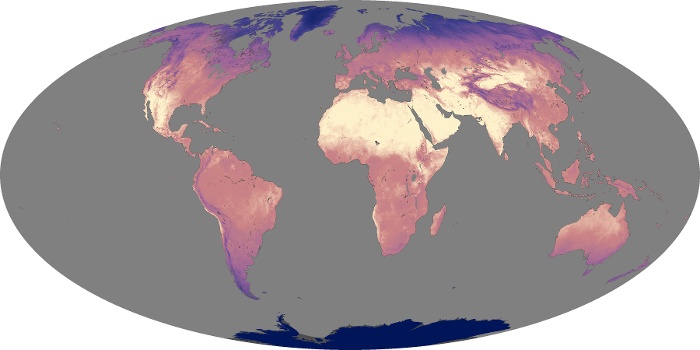

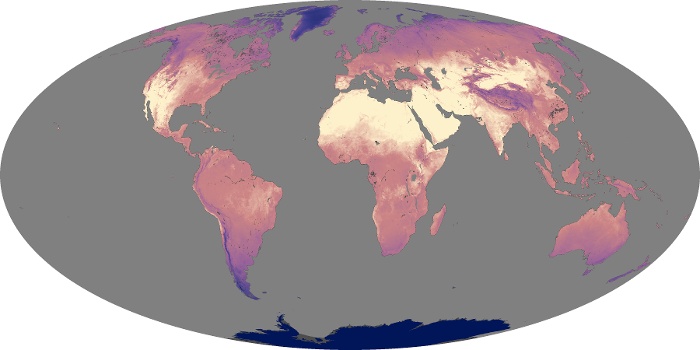

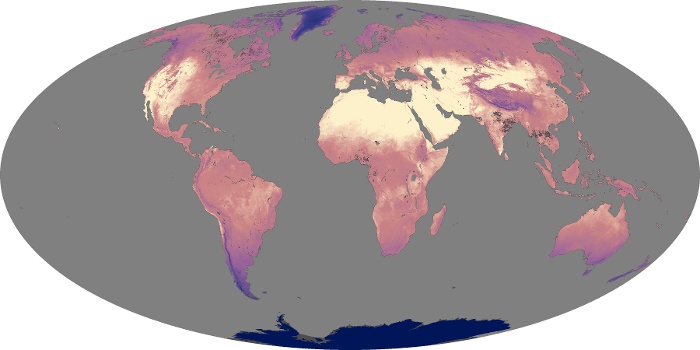

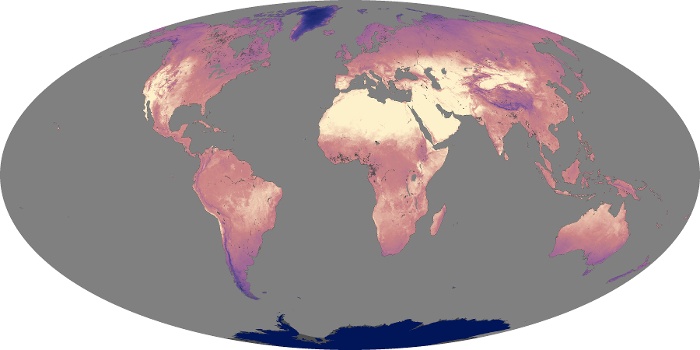

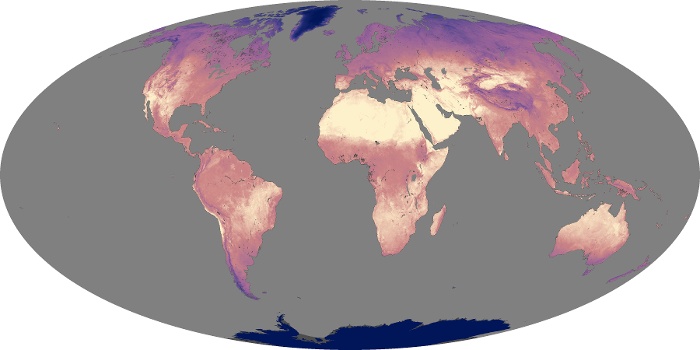

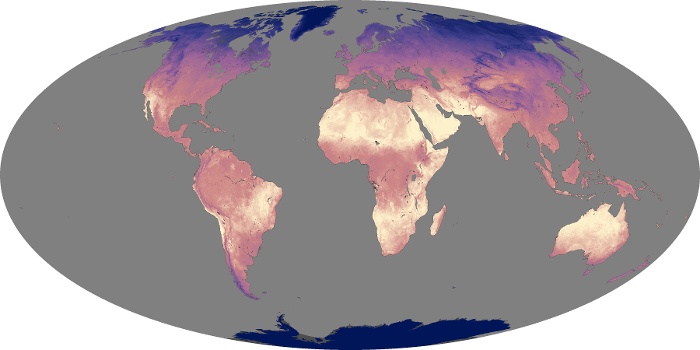

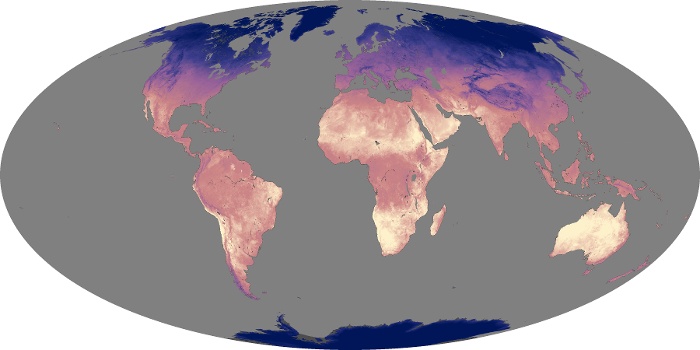

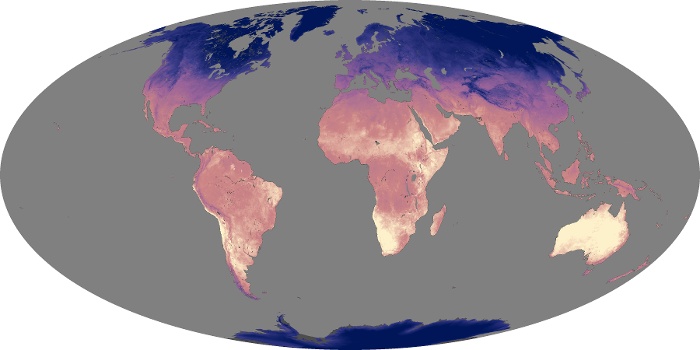

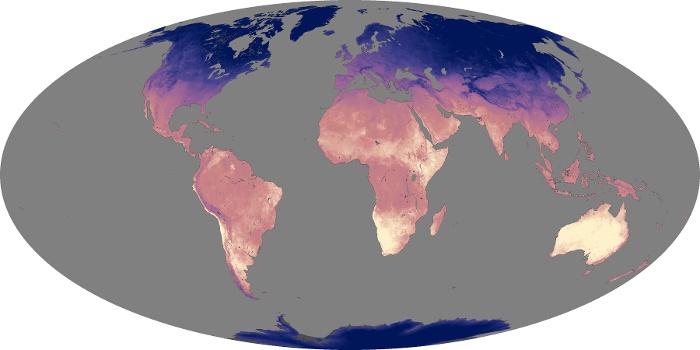

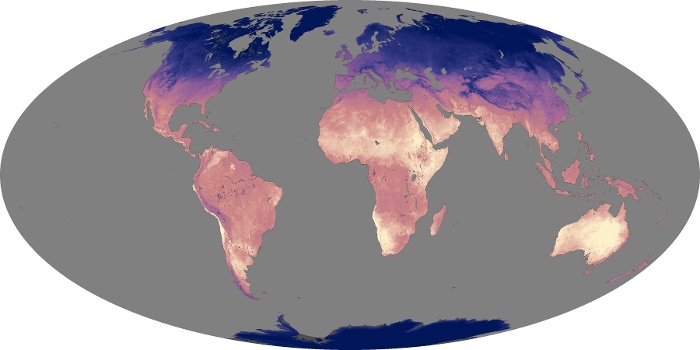

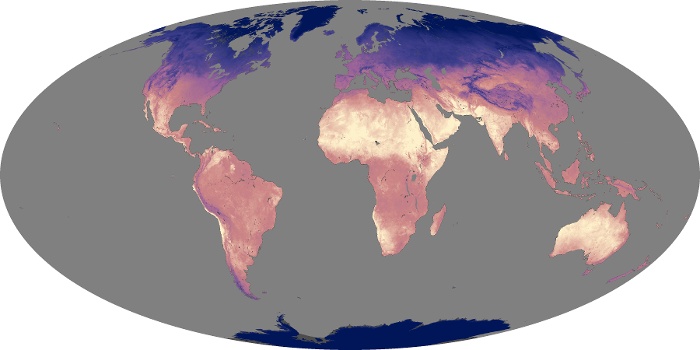

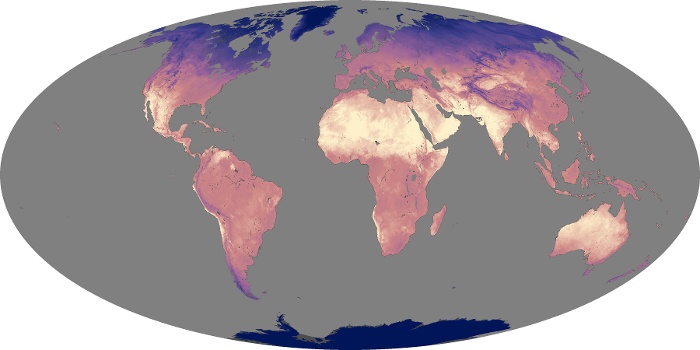

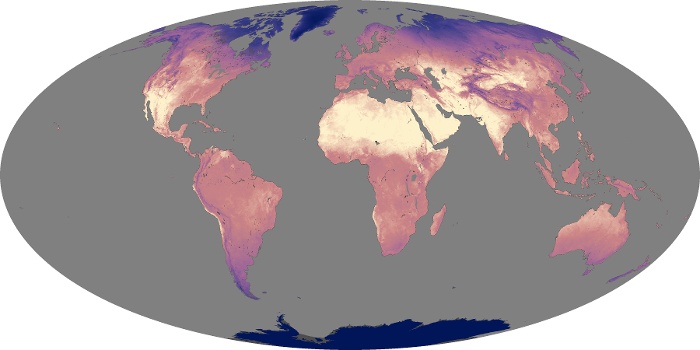

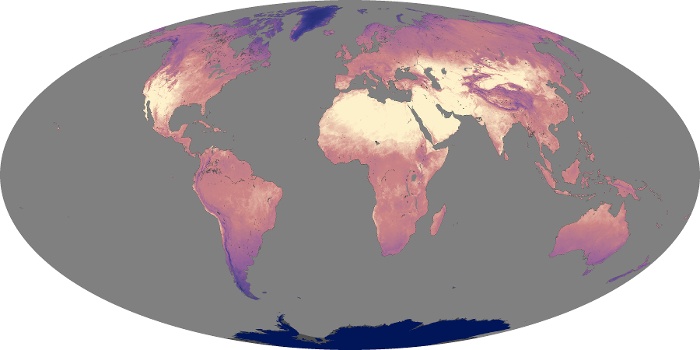

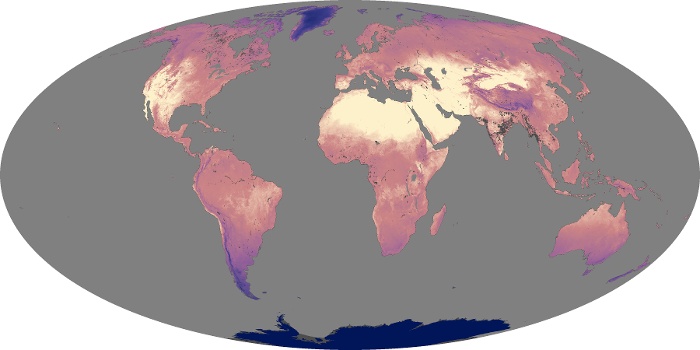

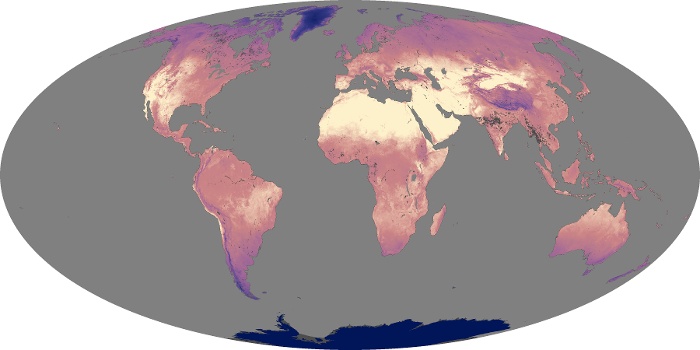

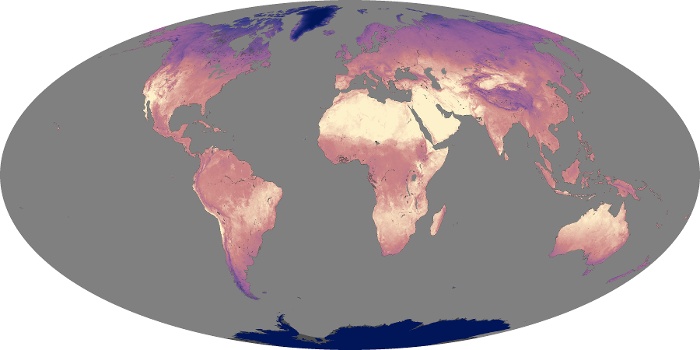

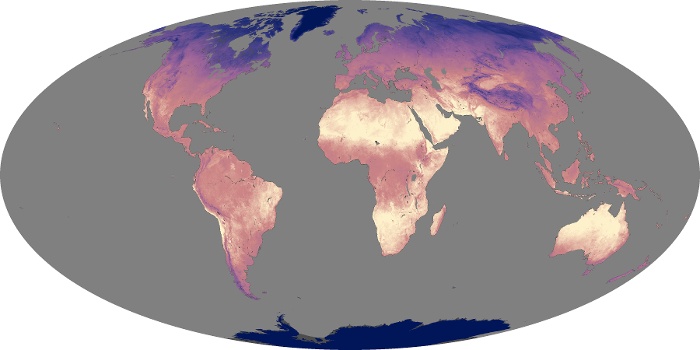

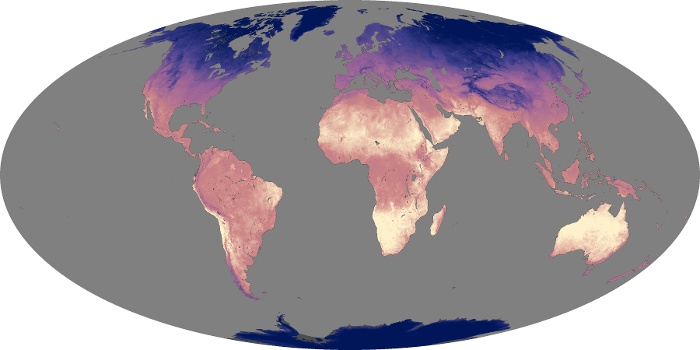

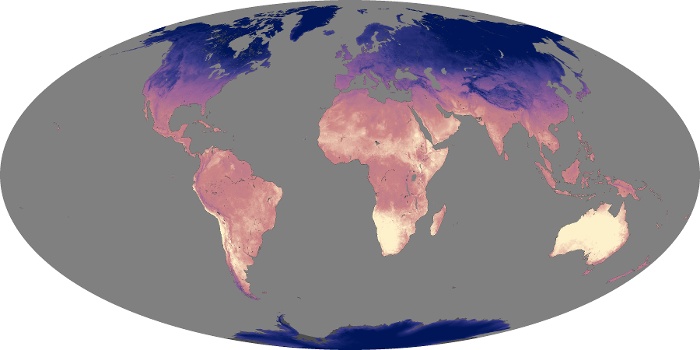

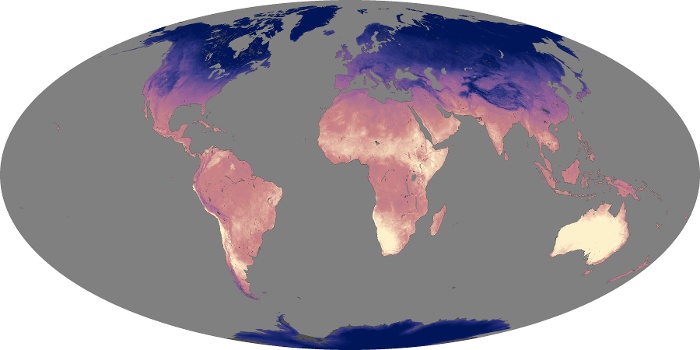

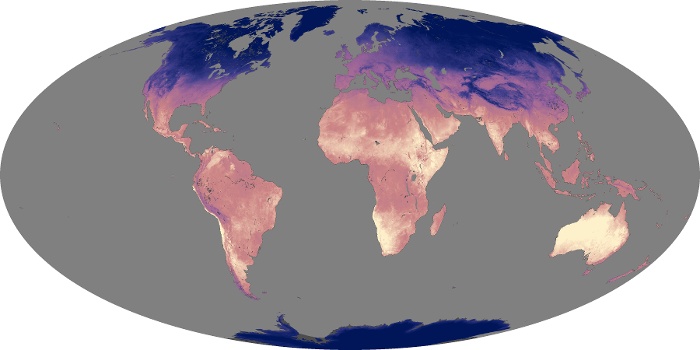

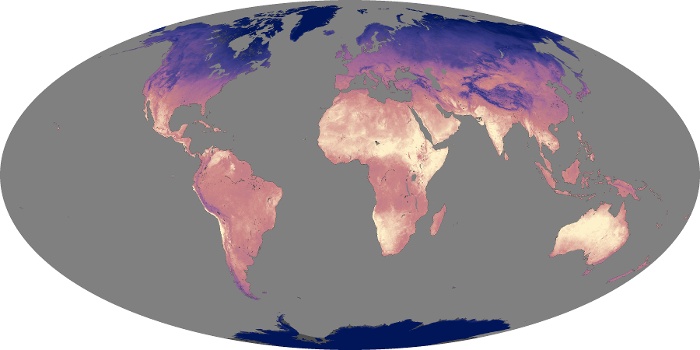

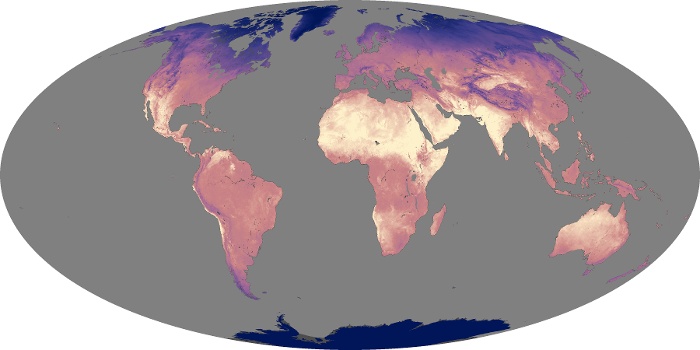

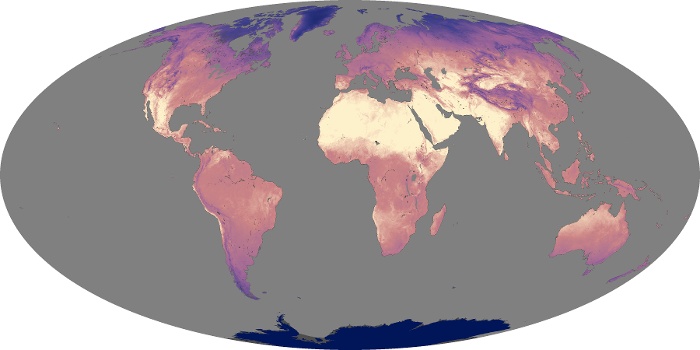

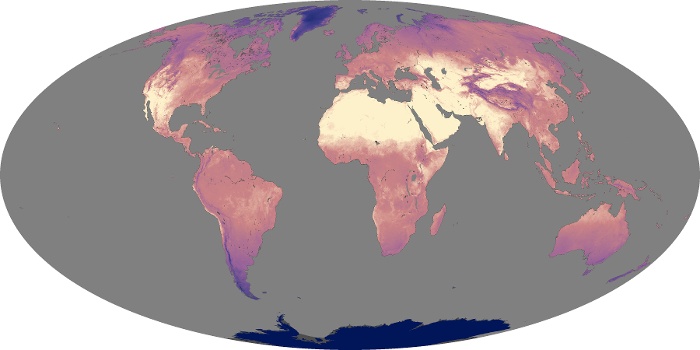

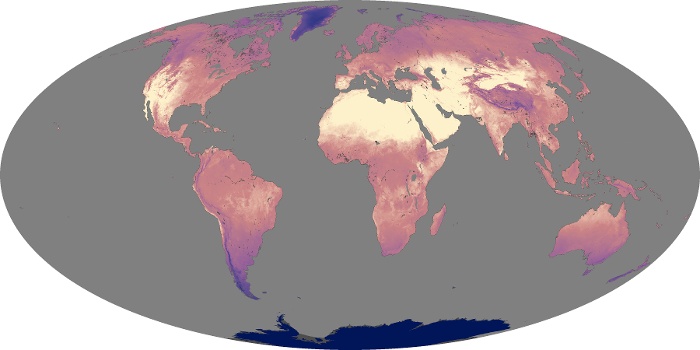

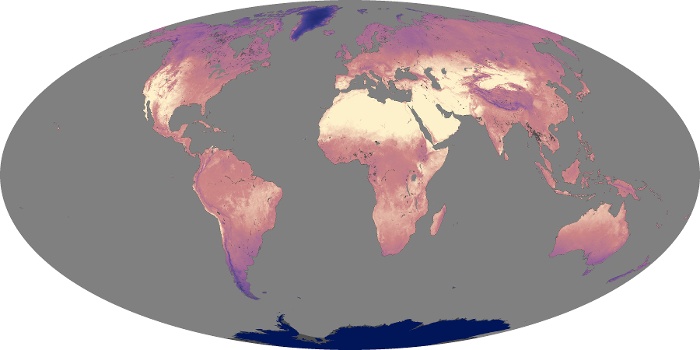

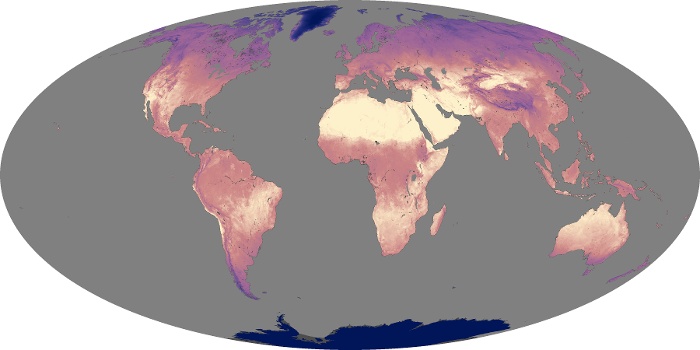

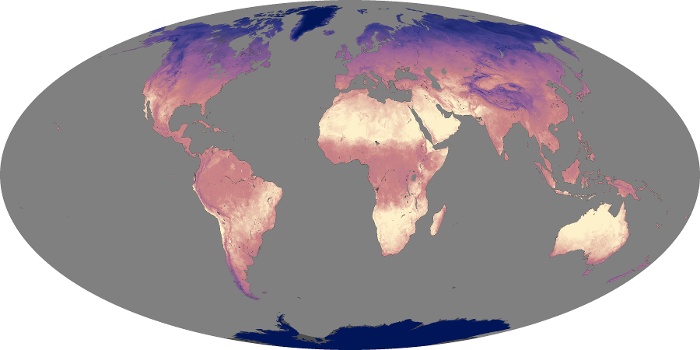

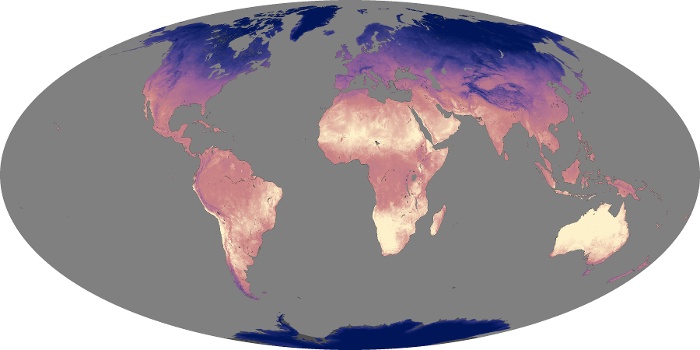

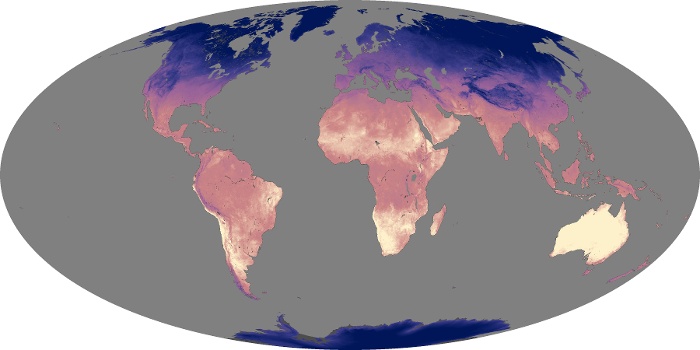

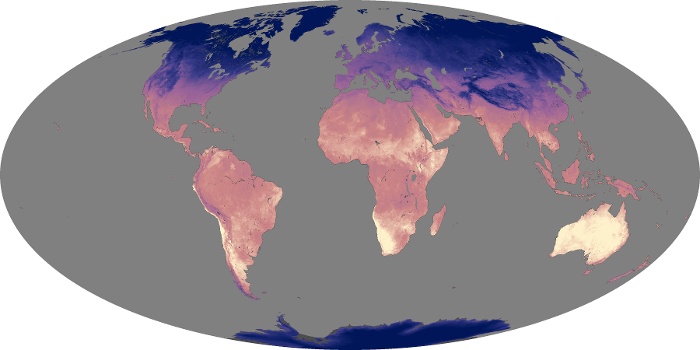

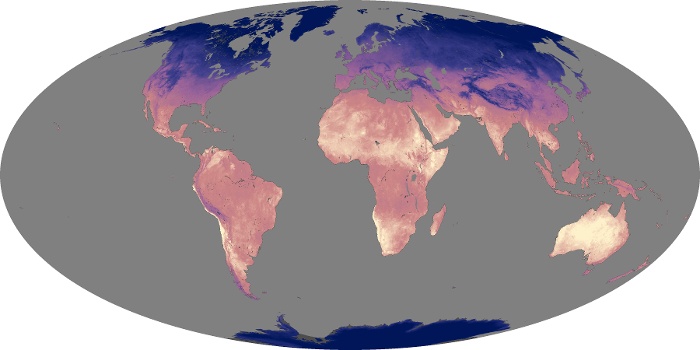

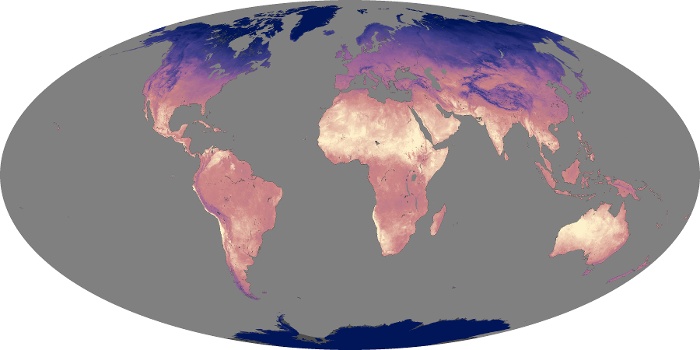

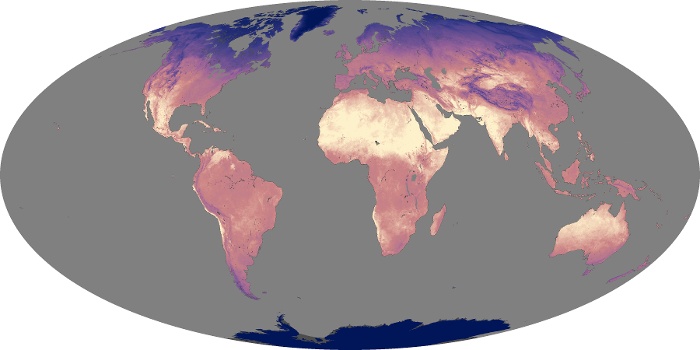

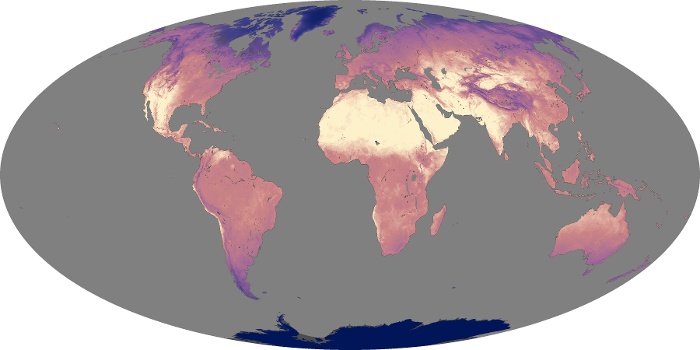

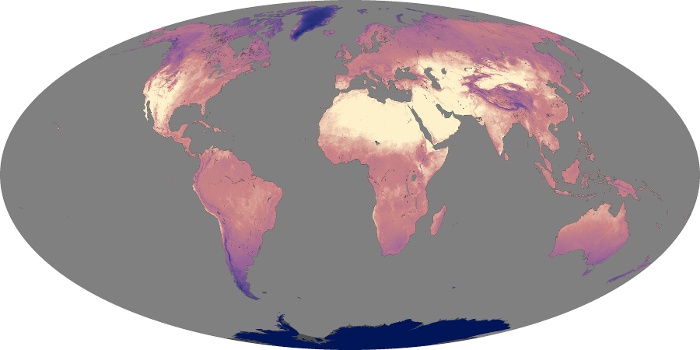

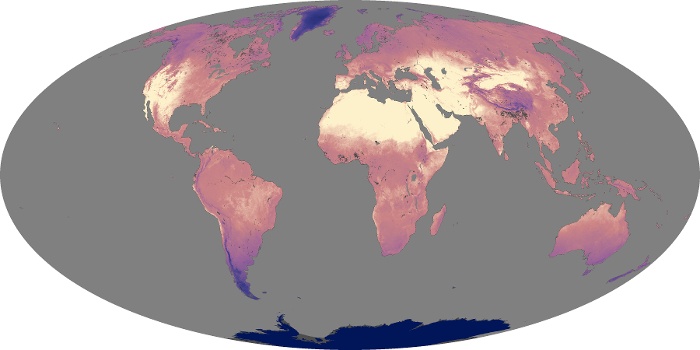

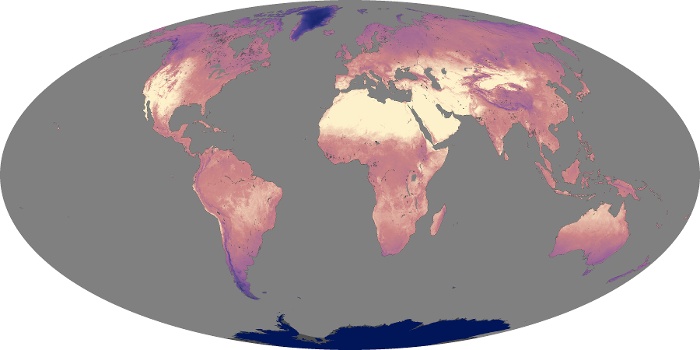

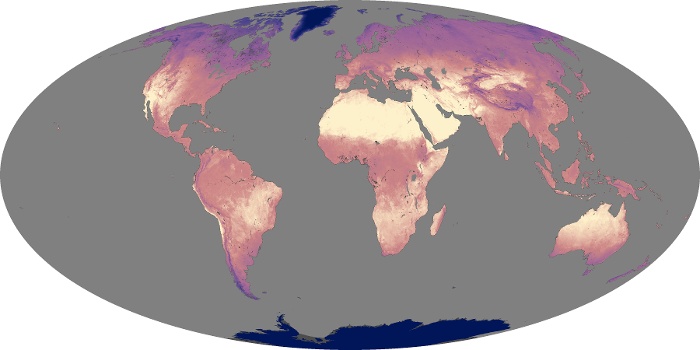

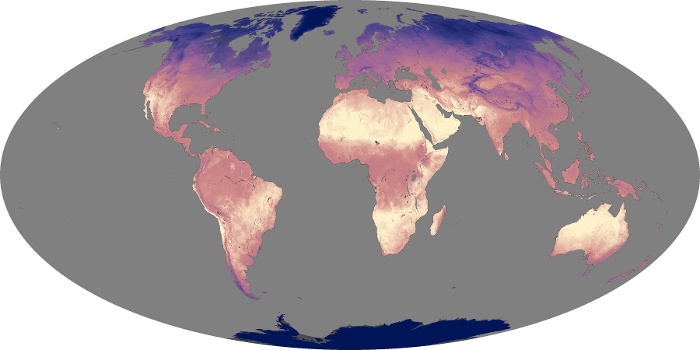

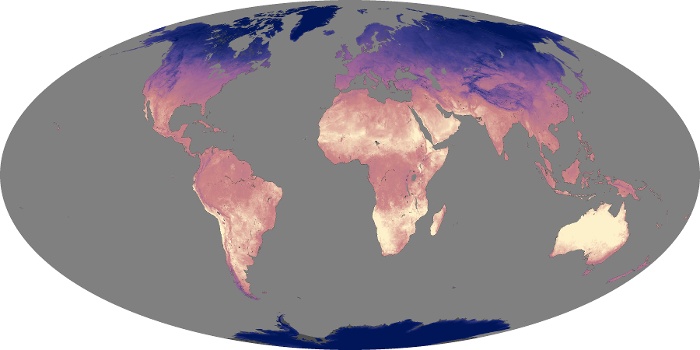

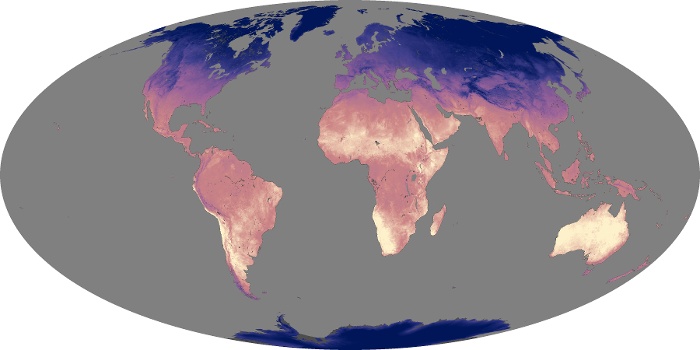

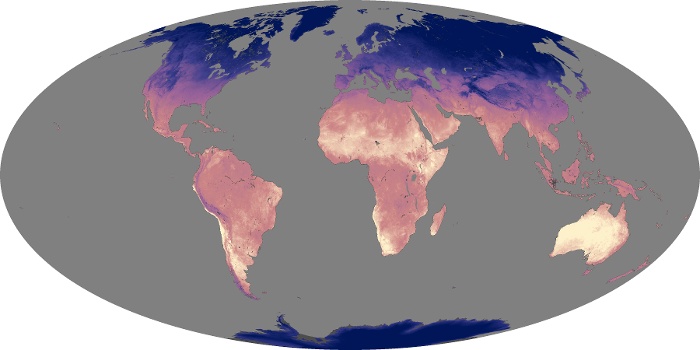

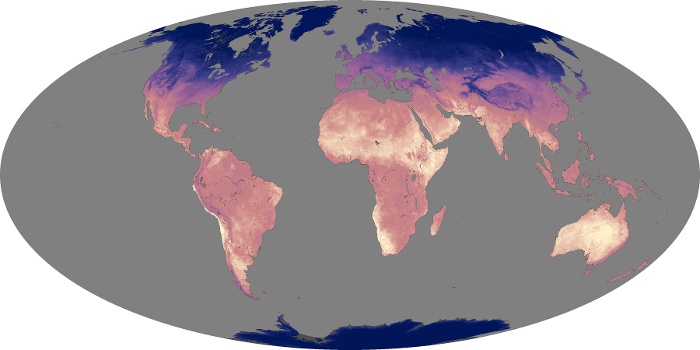

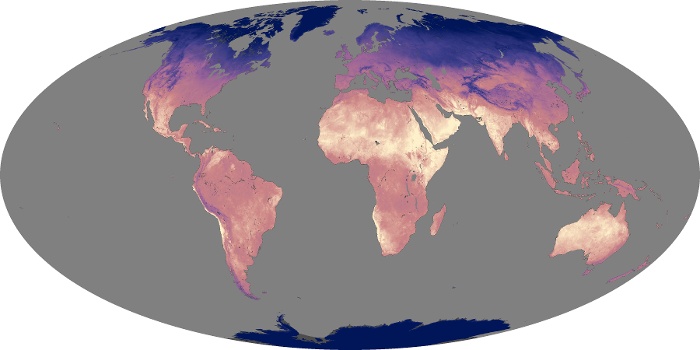

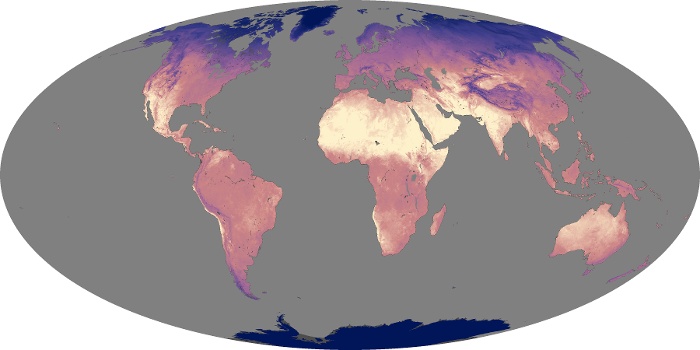

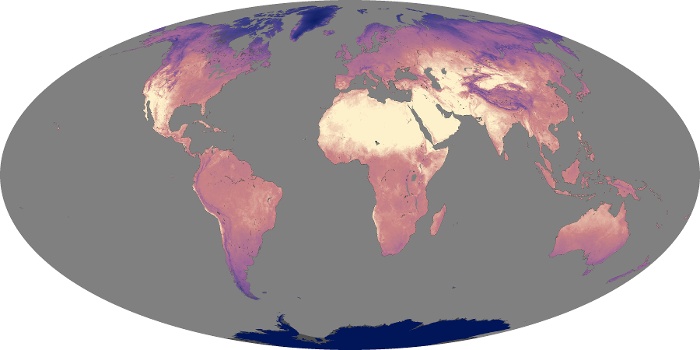

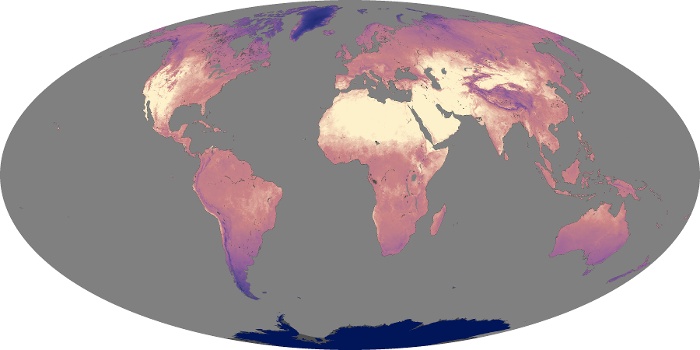

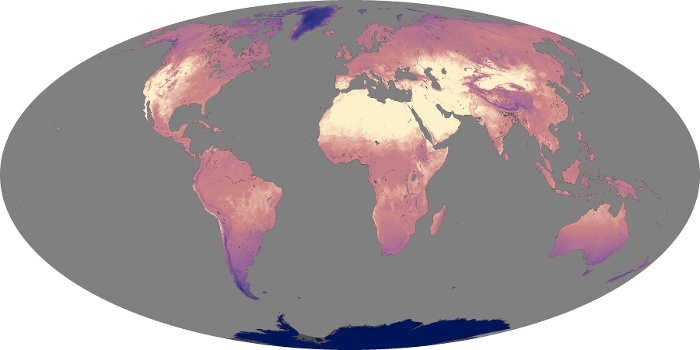

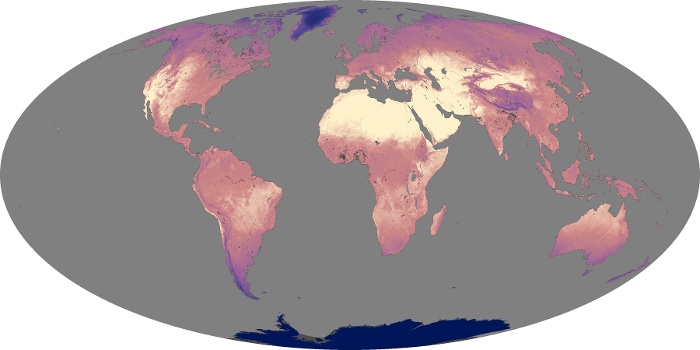

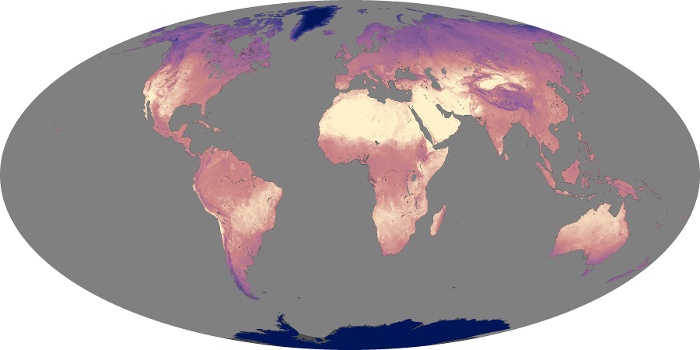

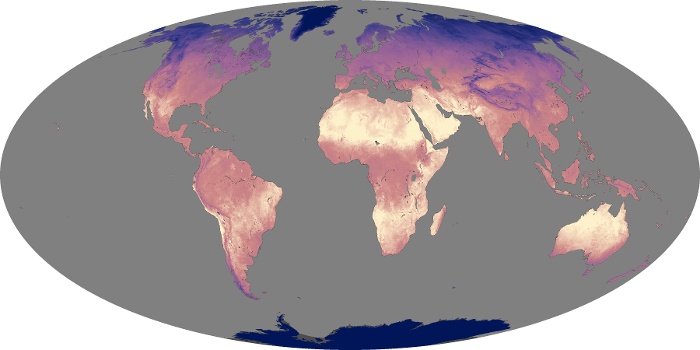

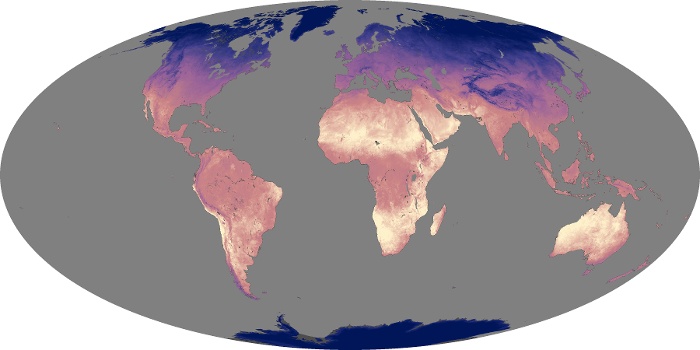

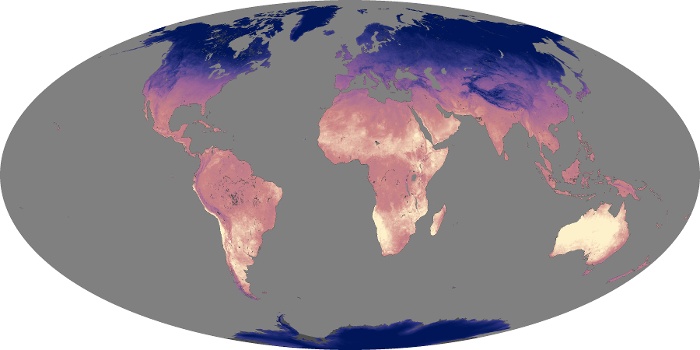

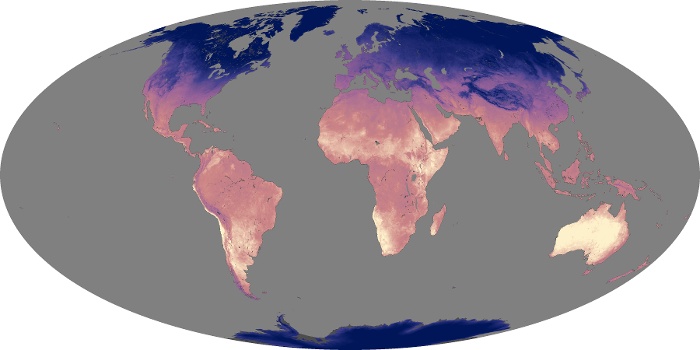

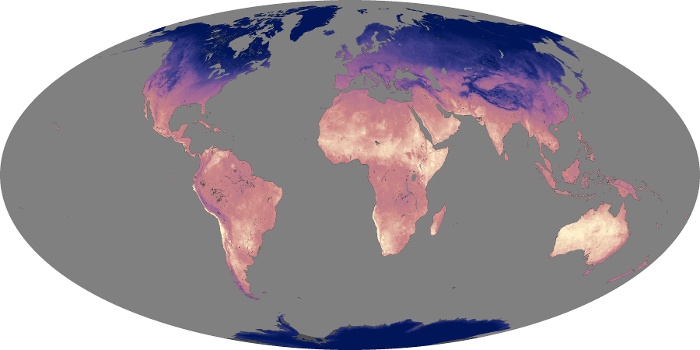

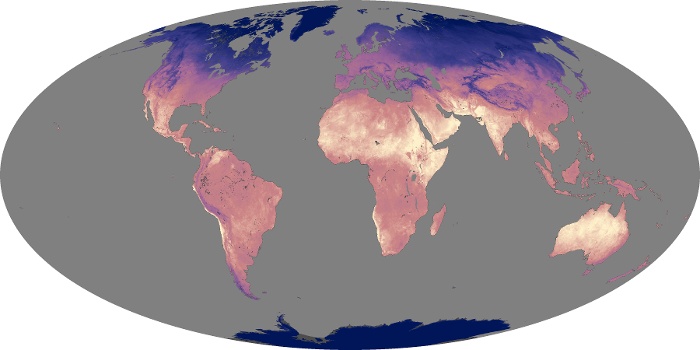

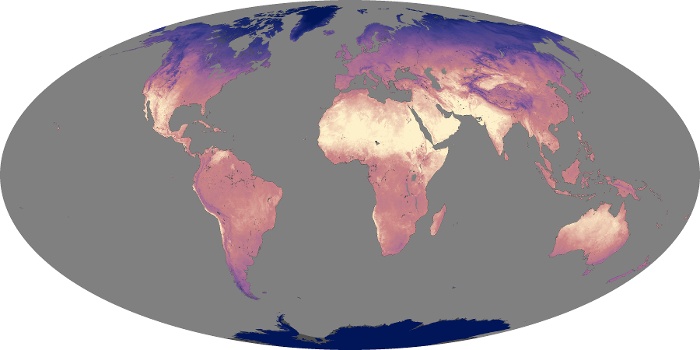

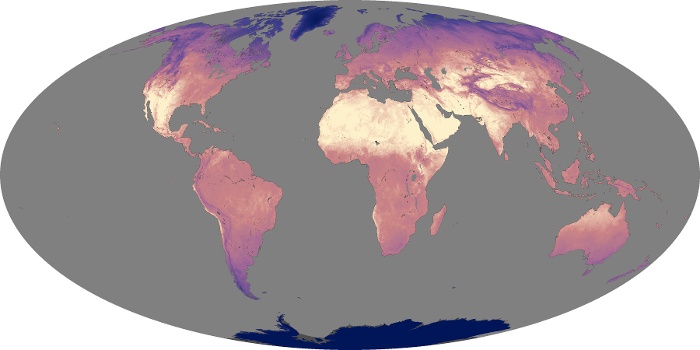

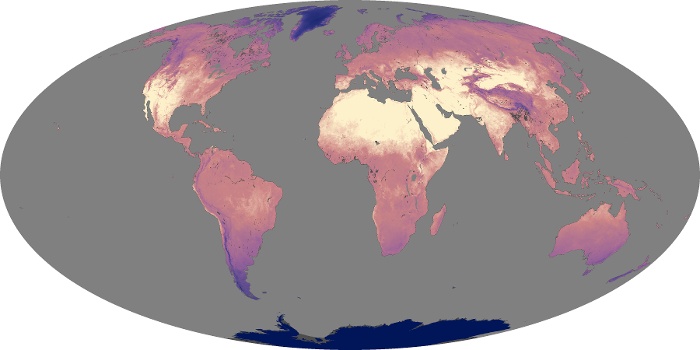

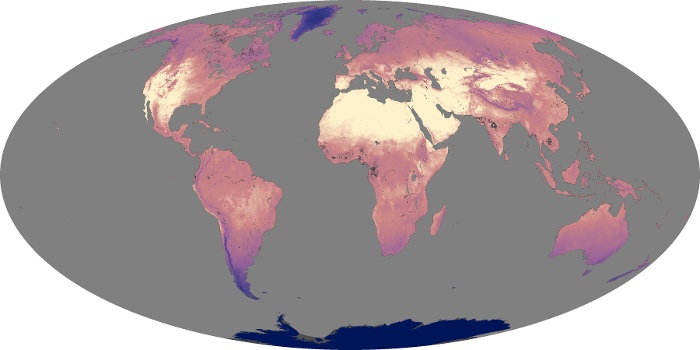

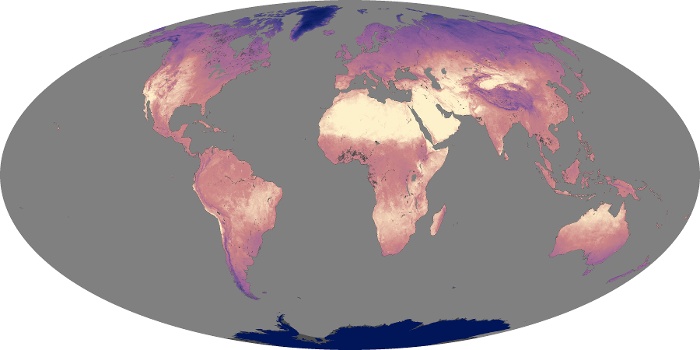

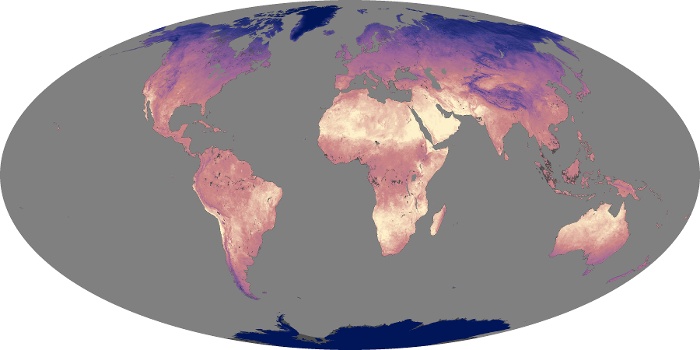

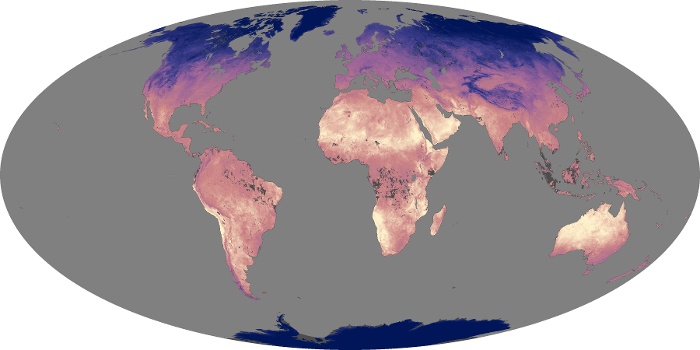

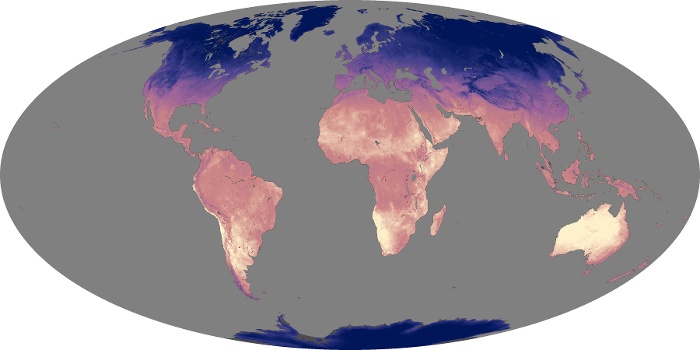

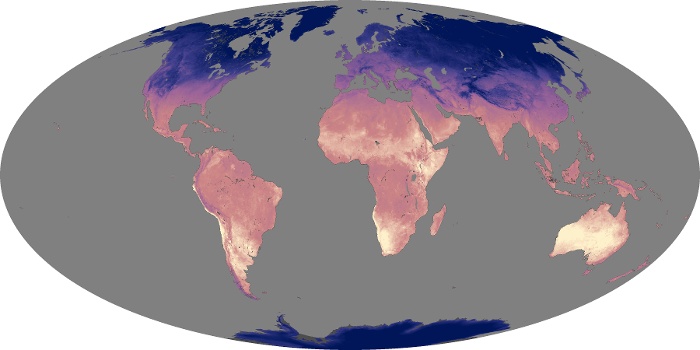

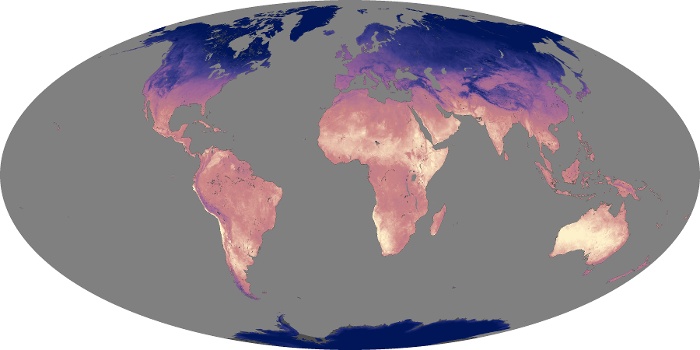

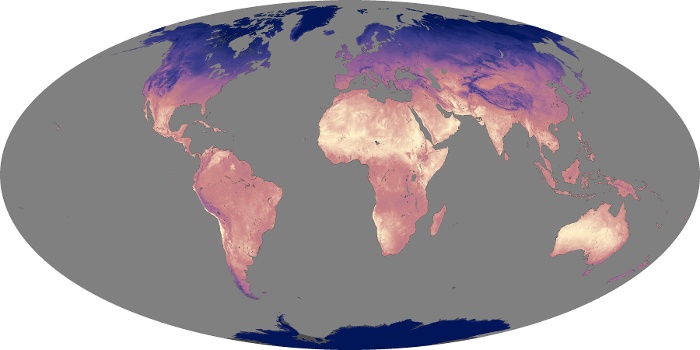

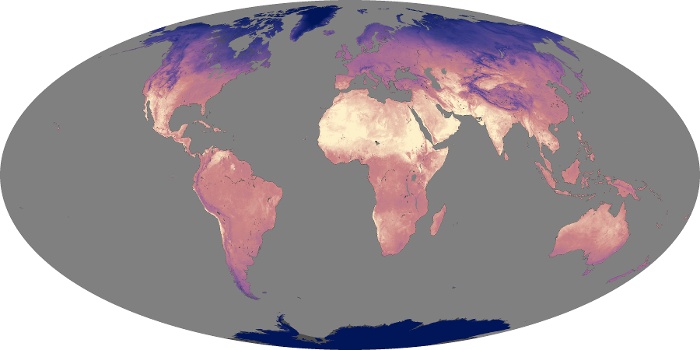

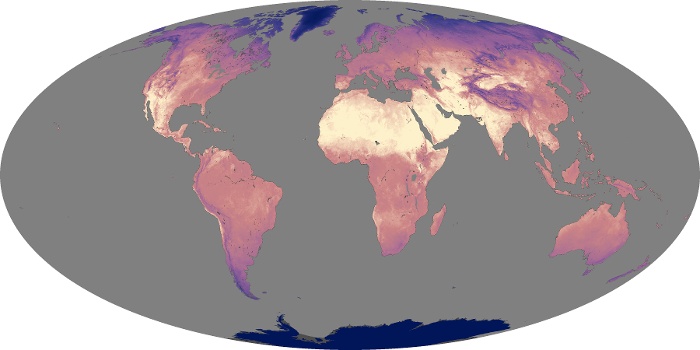

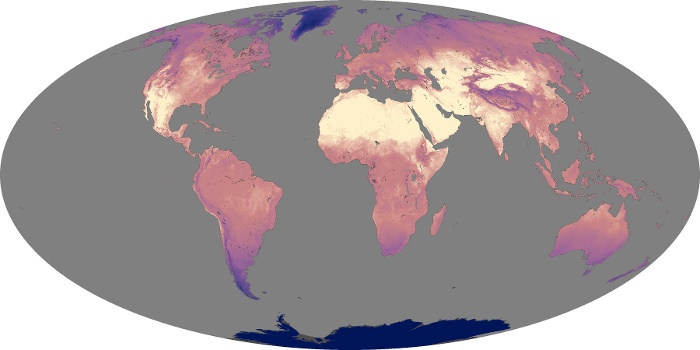

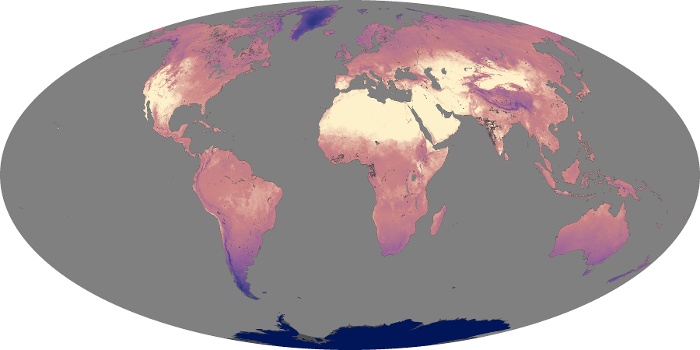

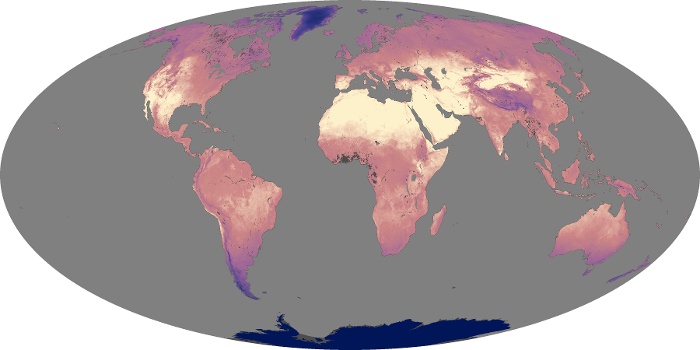

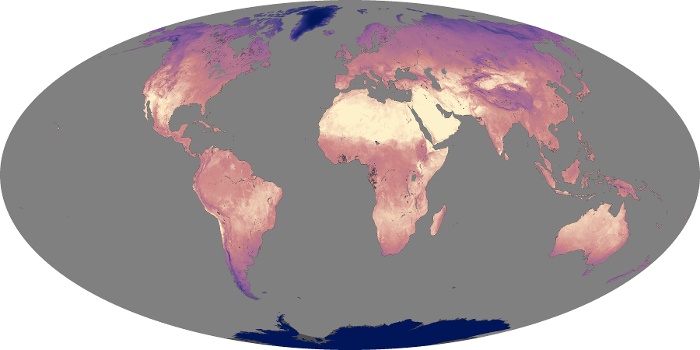

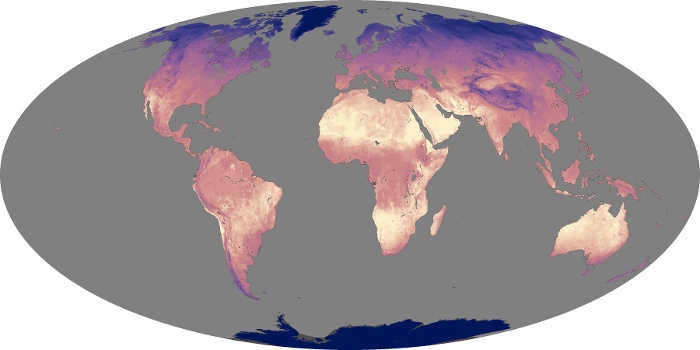

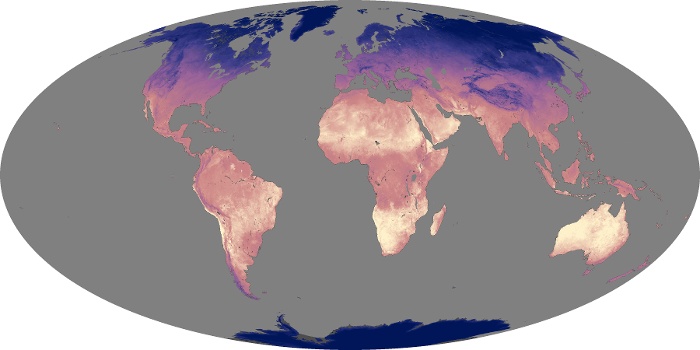

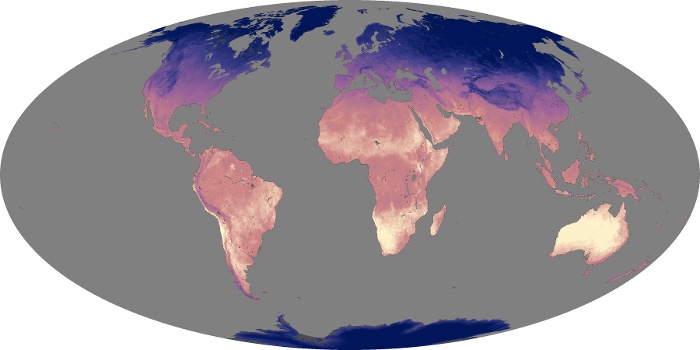

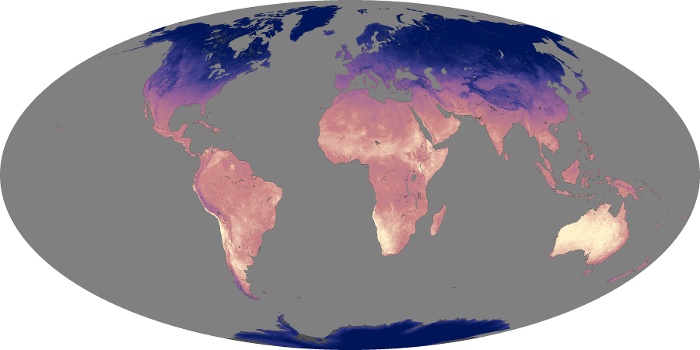

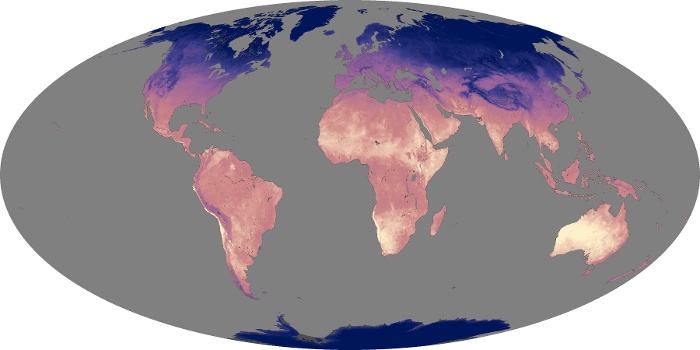

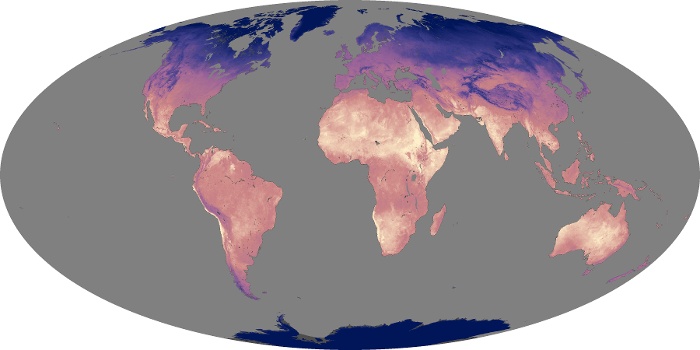

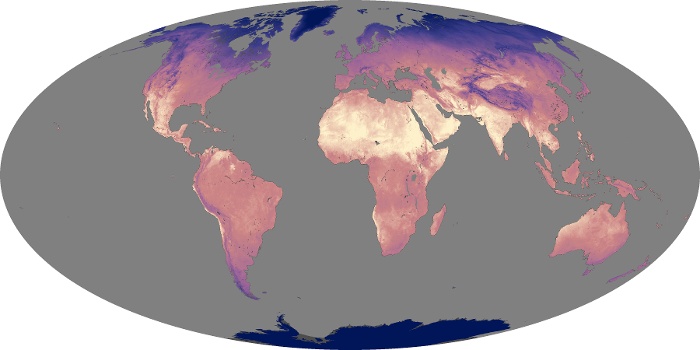

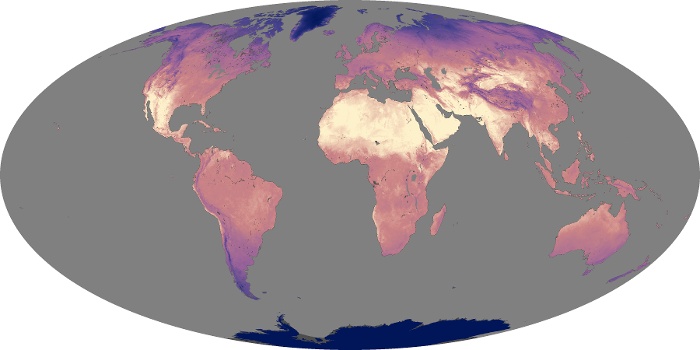

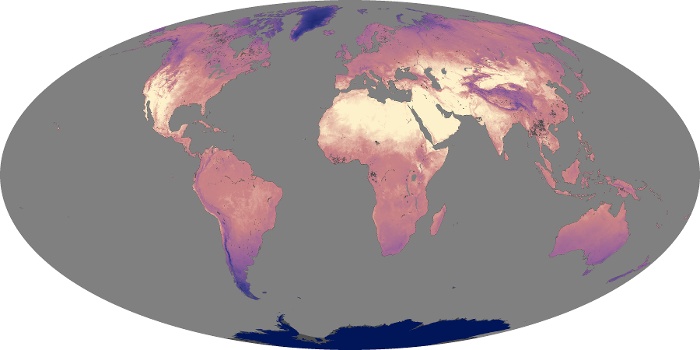

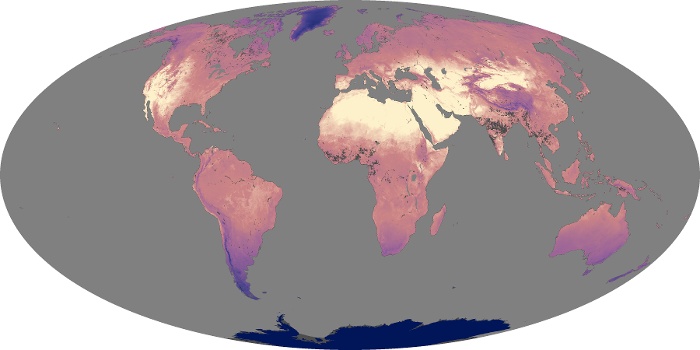

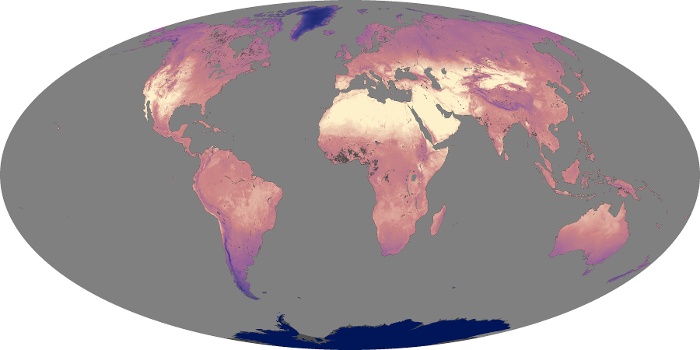

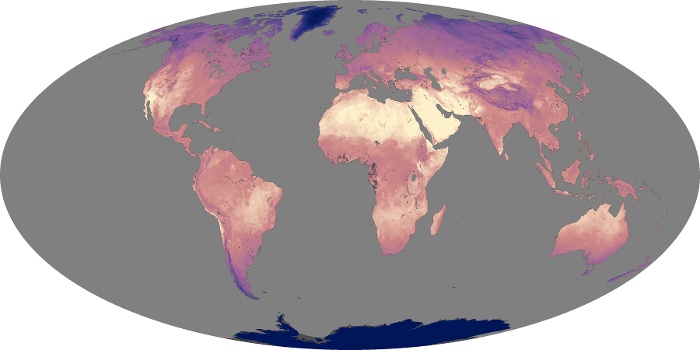

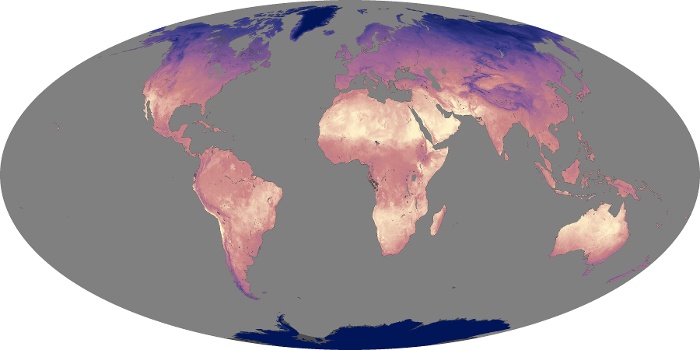

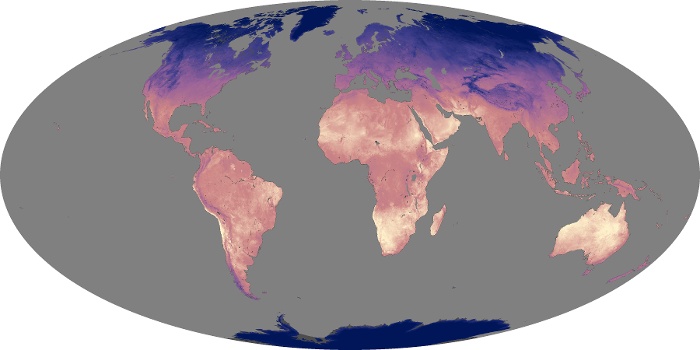

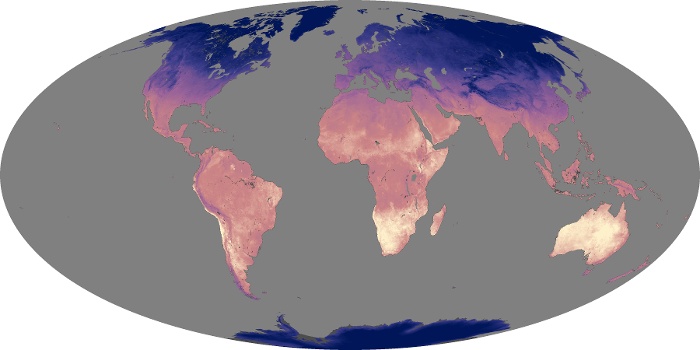

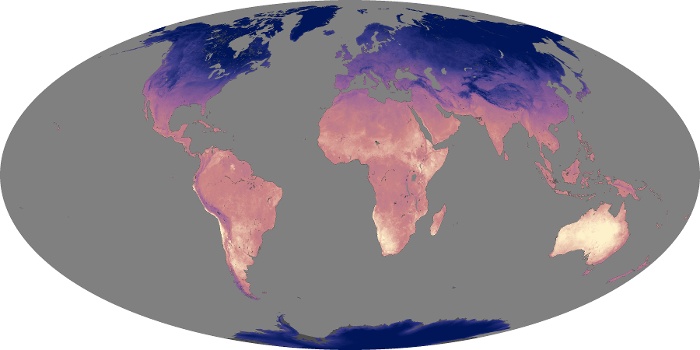

The maps shown here were made using data collected during the daytime by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite. Temperatures range from -25 degrees Celsius (deep blue) to 45 degrees Celsius (pinkish yellow). At mid-to-high latitudes, land surface temperatures can vary throughout the year, but equatorial regions tend to remain consistently warm, and Antarctica and Greenland remain consistently cold. Altitude plays a clear role in temperatures, with mountain ranges like the North American Rockies cooler than other areas at the same latitude.

Scientists monitor land surface temperature because the warmth rising off Earth’s landscapes influences (and is influenced by) our world’s weather and climate patterns. Scientists want to monitor how increasing atmospheric greenhouse gases affect land surface temperature, and how rising land surface temperatures affect glaciers, ice sheets, permafrost, and the vegetation in Earth’s ecosystems.

Commercial farmers may also use land surface temperature maps like these to evaluate water requirements for their crops during the summer, when they are prone to heat stress. Conversely, in winter, these maps can help citrus farmers to determine where and when orange groves could have been exposed to damaging frost.

View, download, or analyze more of these data from NASA Earth Observations (NEO):

Land Surface Temperature